This is the first “PILOT season” episode of Philosophy Bakes Bread from 2016, when it came out only as a podcast. The episode begins with a very personal story about how stoic philosophy can make a profound difference for the better when we encounter difficulties beyond our control.

(25 mins)

Click here for a list of all the episodes of Philosophy Bakes Bread.

Subscribe to the podcast!

We’re on iTunes and Google Play, and we’ve got a regular RSS feed too!

In this and the subsequent three pilot episodes, the material was all drafted in advance. This means that for these four episodes, we have a transcript, available here below (or after the “more…” link).

[Musical intro]

The philosopher Aristotle had a lot to say about happiness and how to get it. He also admitted, though, that luck, good or bad, can make happiness far easier or harder to attain. I learned that lesson the hard way. As an incredibly lucky person, with loving parents and brothers and a great education, I fell in love with and married the most amazing woman and we chased our ambitious goals. A mentor of mine likes to remind me of a line often attributed to Thomas Jefferson, whenever I talk about how lucky I am. “I’m a firm believer in luck,” the saying goes, “and the harder I work, the luckier I get.” There’s certainly some truth to that. Some luck, however, is beyond our control.

I had my doctorate and a tenure-track job, one of the most secure forms of employment left in the United States. Annie had her master’s degree and had started her own doctoral program at Vanderbilt. She had been working in a highly employable field in Illinois and her prospects for work, even in small-town Oxford, were great. The future was bright and many of our goals were reached, while other goals were down a clear path ahead.

In August of that year, just before moving to Mississippi, our daughter Helen was born. We named her after my grandmother on my Dad’s side. It was a long delivery which started late in the evening. We were exhausted. When asked whether we wanted the baby in the room with us, we took the hospital up on their offer to watch Helen in the nursery. Without realizing it, we may have saved Helen’s life with that decision.

On our little girl’s first day of life, the nurses watching her witnessed apnea. She stopped breathing. Shortly after being told about the first time, I witnessed it happen myself. Within two seconds our little girl’s body turned from a light pink to a medium blue. A nurse swooped to Helen and got her breathing again, and her color returned in an instant. I had never seen anything like it. This nurse was in control and did it again. It is amazing what we can control.

The part we could not control was the cause. At childbirth, a mother’s blood is “hypercoagulable.” That means that it is ready to clot. Clots are important when you bleed, as they are the mechanism which stops bleeding. What this means is that while in delivery, a mother’s blood is ready to protect her, naturally. It’s pretty amazing. At the same time, those clots can go wherever blood goes. A baby’s brain is very small and has many tiny little blood vessels. In our daughter’s case, one of those vessels became clogged with a clot. On her first day of life, our little girl suffered a stroke. They call it an infarction. The injury also caused seizures, which we only saw in the form of her apnea.

More than else in my life, I wanted at that time powers that were not in my control. I wanted to do anything I could to help my little girl heal and thrive. Unfortunately, no amount of money, manpower, or technology could change what had happened. We did everything we could, including a helicopter trip to a specialist hospital, to one of the best children’s hospitals in the country. There simply are things that are within our control and things that aren’t. Aristotle was right. Sometimes luck makes it very difficult to be happy, even if everything else in your life felt like hitting the lottery.

Fortunately, another great philosopher had some invaluable lessons for me and my wife. We can say without hesitation that we are very happy people, even if it took some time, effort, and especially some deeply thoughtful and sober philosophy.

Today I am telling you my own very personal story to introduce you to this podcast series. Philosophy Bakes Bread is a program meant to turn a common phrase around – one which says that “Philosophy bakes no bread.” In some countries, like France, people are proud of philosophy. They understand its importance and even teach it in high schools. In the United States, we evade philosophy, as Cornel West has put it. We joke and belittle the philosophy major. “What does the philosophy major say at the fast food restaurant?” The answer “Would you like fries with that?”

Some politicians criticize less “employable” majors like philosophy, arguing that we should create incentives for people to major in things that are practical. They think they are promoting economic growth when they laugh at philosophy majors. PayScale.com, often cited by the Wall Street Journal, does show that Philosophy majors earn less money in average starting salaries than do people who major in Chemistry, Political Science, Accounting, Architecture, IT, or Business Management. What critics fail to realize is that by mid-career, Philosophy majors earn an average median salary greater than every one of those majors. You don’t have to be great at math to realize that mid-career salary performance is the far greater indicator of money-making over one’s lifetime. Of course, philosophers don’t usually go into the field for the money.

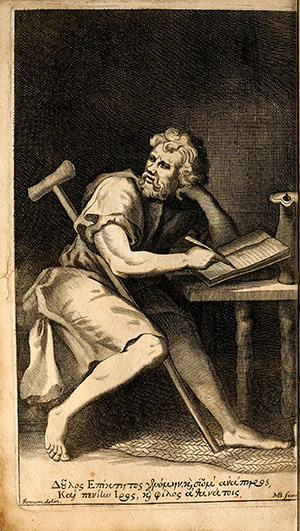

I once enjoyed a rich discussion about stoicism with student-inmates in Mississippi’s Parchman Prison. With that group, I decided to talk about some of the philosophical ideas that made the biggest difference in my life. Undergraduates in college and inmates in prison both have had a great deal to say and appreciate in the work of a famous stoic philosopher named Epictetus.

When Annie and I were learning all we could about our daughter’s challenges, we found no shortage of words of consolation. It might be difficult to understand without experiencing it, but after hearing for the hundredth time that “everything happens for a reason,” it becomes pretty upsetting. It ignores what philosophers have long called “the problem of evil.” The reason people propose for suffering in the world is some intention or necessity that God had for it. So, when children die slowly and painfully, or just suffer, there’s said to be a reason. For those who find some consolation in that idea, I’m very happy. To reject the statement doesn’t mean that one has to discard religion or God. Something akin to the idea that “everything happens for a reason” was part of what Epictetus taught us. The difference, though, is subtle yet powerful.

Epictetus in his famous work, called the Handbook, believed that the universe has an “author.” He says at times that just as an archer does not aim to miss his target, neither does the author of the universe. In other words, this is the universe that the author intended. Epictetus does not suggest the reason for suffering in the world. He does not pretend that there is some answer that we will eventually learn. Instead, he teaches us how to be happy despite the difficult things that happen to us in life.

Rather than imagining God’s reason for causing my daughter’s injury, Epictetus asks me a question. He asks “Who promised you a healthy child free of difficulty?” He reminds me that not one day in my life or hers was promised to us. When we see that there never were any offers or guarantees in life, it turns out that there have been almost an infinite set of good fortunes. After all, while I may have wished my daughter perfect health, in the room next door to ours at the hospital, it turns out that a woman was giving birth to a stillborn child. We were asked not to celebrate too loudly about our daughter, out of consideration for our neighbor. Our daughter is with us. I can give her hugs and kisses, and she can give them back. If I can’t accept that as evidence of our good fortune, Epictetus would tell me, I am choosing to be unhappy.

When we focus on things outside of our control, he explained, we subject our happiness to chance. Things that we cannot control might turn out just the way we want them to be, or they might not. So, when we let our happiness depend on what is beyond our control, we are rolling the dice – but we don’t have to.

Epictetus tells us that we can choose to be happy. We can also choose to be free. The person who fails to accept things beyond his or her control is in turn controlled by those things.

For those who don’t know me, I can reasonably tell you that I’m a pretty big and tough guy. I was a wrestler in high school who competed in the state competition at a weight class around fifty pounds above my own weight. I say this to preface my demonstration of Epictetus’s point. One day, in our daughter’s first year, I was watching some nonsense on TV. A commercial came on in which a woman was all excited about her wedding, and then was in her dress and it was the big day. Out of nowhere, I was hit like a ton of bricks and was balling, crying like I never had before. It dawned on me that I didn’t know whether my daughter would one day get married. I didn’t know whether she would feel that kind of happiness. I had lost control and realized the scope of how much I had never considered would be different for her, compared with kids who never suffered a stroke.

It is true that one can recover from a stroke. There are some children who can suffer from one early on and then later you wouldn’t know it. A doctor told me that some children will only reveal the history of their stroke when they run. They might hold an arm oddly as they run, for instance, or have some kind of subtle artifact from the early injury. The brain is malleable. It may not heal a portion that has died, but the parts of the brain next to an injury can often take up the function of the injured area. It’s amazing. In fact, in Helen’s case, her injury happened in a part of the brain that controls her right arm and leg. Despite that, she can use both of them, even if not evenly.

In her case, the bigger impact came with the epilepsy she later developed. One in six thousand kids have a stroke at birth. Only about 2,500 children each year are diagnosed with Infantile Spasms, the form of epilepsy she developed months later. Most kids with such seizures had some form of brain disorder or injury, and most kids with this kind of epilepsy are developmentally impaired in later life.

In that experience, I realized something that troubled me. I saw that my own failure to imagine that she could choose between toys prevented me from giving her choices. My own unconsidered assumptions might have slowed her progress, I feared. Many ideas like that generated enormous stress, anxiety, and anger – at myself.

I mentioned that Epictetus’s stoic philosophy is not just about avoiding big swings of mood. In fact, his insights have taught me to be happy. How can I blame myself for something I had no idea to imagine or try? Of course, I don’t ever want to be the cause of a problem or an obstacle to her progress, but as many loved ones have pointed out, Annie and I have really tried to do everything we could as best as we could do it.

Epictetus’s central idea may seem simple: Accept those things outside of your control and make any changes for the better with respect to those things that are in your control. It is far harder to do than it may sound.

As I said, I talked about these ideas with inmates in Parchman Prison. They taught me a connection I had somehow never made. They realized, quite rightly, that the Serenity Prayer captures the stoic ideal:

God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change,

The courage to change the things I can,

And the wisdom to know the difference.

The inmates recognized instantly that the teachings of stoicism underlie this humble prayer. In fact, when I thought more about it, I saw a solution to my earlier anger, directed at myself. When I was mad at myself for not realizing that our little girl could choose between toys, I did not yet have the relevant wisdom, which someone else kindly revealed to me. In that sense, I was fortunate that a caring person taught me something that I didn’t know about how to take better care of my little girl. Rather than directing anger at myself, consider how much happier it made me to feel grateful to the people who taught me an important lesson.

No one promises us health or long life. There were no guarantees on the box. I’ll end with three last points about stoicism and its impact on my life, with the ways in which it has baked philosophical bread for energizing me and for sustaining my happiness.

The first is that Epictetus presents us with some ideas that will seem impossible, but they make a point. When someone else wrecks his or her car, we tell ourselves that such things happen. We might feel sympathy for others, but we don’t take it as a personal loss or injury. When someone else’s child gets sick or suffers terribly, we might feel lucky that it was not our own, and soon enough our minds are back to focusing on our own tasks and goals. Epictetus teaches us that when we wreck our own things, or when our own family members are sick or suffer, we should react in the way that we do when it was someone else’s loved one. We certainly should attend to him or her, but consider how quickly we recover and accept what is not in our own control when the ill-fortune comes to someone else. He believed that we can achieve that kind of acceptance and control over our own emotions and reactions – if we try and practice it – even if it is our family that suffers.

Anything can seem hard to do the first time we try it. Some things could seem impossible. Stoicism does not mean accepting that we have no control without trying. After all, how can we know whether something is in our control or that it isn’t? I know of no other way than to try. Some things we can tell pretty easily. No one has ever flapped his or her arms fast enough to take off from the ground. When we understand the physics involved, we can explain why it won’t work. The same can be said for limitations that come from health challenges. Some crazy things can still be worth trying, of course. Without that, Spud Webb may never have discovered that at 5 feet 7 inches he would be able to dunk a basketball or to play in the NBA. One source says that he was dunking the ball in junior high, back when he was 5 feet 3 inches tall. Given that, stoicism doesn’t mean giving up. After all, not giving up is something typically in our control. The difference is that when we try yet fail, it’s vital to accept that failure, at least for that particular effort.

I have found in this way of thinking the way to happiness. I keep trying every day to do whatever I can for my daughter. I have also realized that all parents worry about their children and whether or not they are progressing to the extent of their potential. Other parents worry about their children too. And, again, parents like Annie and me have had the good fortune not to lose our child, as many have done. Were such tragedy to occur, I would continue to look to Epictetus, to remind myself that I was made no promises. In that sense, I will forever remember the joy I have felt when my little girl gave me hugs and kisses, and said “Dada.” The way to happiness is to appreciate the good fortunes that we have, accepting those things beyond our control, and trying every day to achieve those things which are or may well be within our control. In this sense, there is a way to do as the contemporary philosopher John Lachs, my former professor and still friend and mentor, has said. He explains that we can be both stoic yet optimistic. We can strive for those things that are or may be in our control, so long as we are ready to accept any particular effort’s failure. John is among the happiest people I know, and he and Epictetus have made me happy too.

Stoicism as a philosophy reminds me to think about something crucial in my control: my own behavior toward my wife. I’ve not been perfect. When I think about how important it is to make an effort to show her love and that I am happy, accepting things outside of my control, I feel the difference it makes. The less I behave stoically, the worse I behave as a husband. I know that I am immensely lucky to have her. For one thing, after our first experience, I was scared out of my mind about the dangers in having another child. Somehow Annie was not. She knew that the likelihood of another kind of health problem like the one Helen suffered was tiny. All I could think was that there’s one way we can be sure not to suffer in that way again – by not having another child. That way of thinking on my part would have prevented me from the next great joy in my life, the birth of my son Sam. Annie was right. Sure, we were lucky that he turned out to be healthy and happy, but even a good stoic realizes that we have to take risks. Taking risks is in your control. You cannot benefit from your efforts unless you try them out. My lady had the courage I lacked. Fortunately, these things can be practiced too, and eventually I was ready. I was far more scared than Annie, but was willing to give a go, to accept whatever might happen, and to appreciate the woman who has made me immensely happy.

You can visit the Web site for this podcast online at PhilosophyBakesBread.com, and subscribe to the program to hear future episodes. As I said, I am Eric Thomas Weber. Thanks for listening to Philosophy Bakes Bread, food for thought about life and leadership.

[Musical Outro]