| By Sergia Hay |

I’d like to thank Shane Courtland for his reply to my response to his original posting, “Faith and Betrayal of the Philosophical Method.” I’m eager to continue this conversation about an important and timely subject: free speech in the classroom, and perhaps more broadly within public discourse. As such, it is also connected to other current debates about the appropriateness of trigger warnings, perceived over-sensitivity of some students and fellow citizens, explicit and implicit censorship, and political correctness. (Editor’s note: Check out SOPHIA’s online symposium on trigger warnings here!).

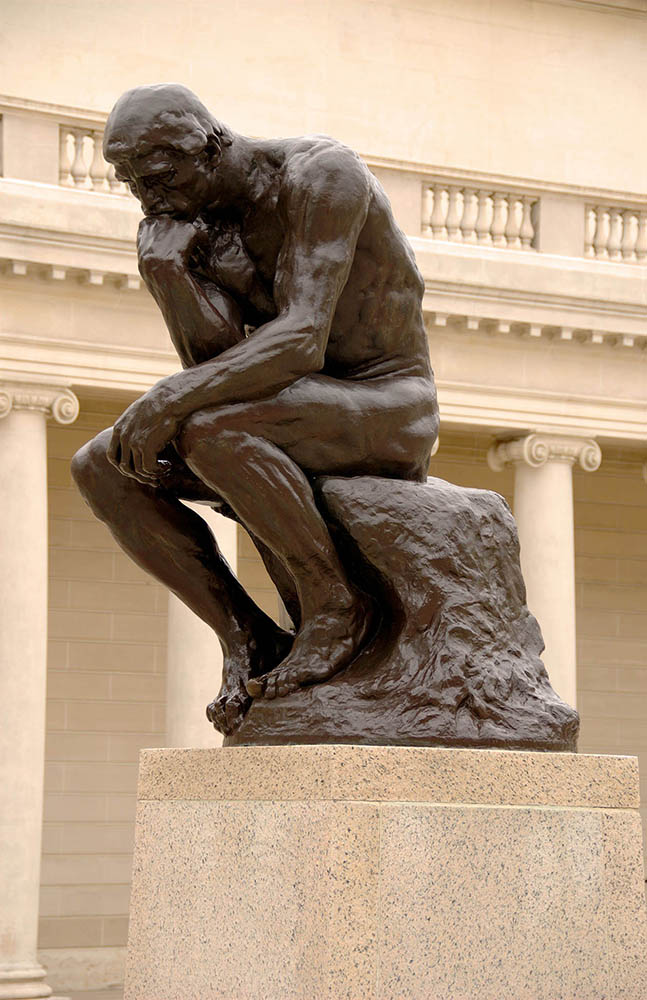

At the end of his reply, Courtland wrote, “It is for the sake of progress, not in spite of it, therefore, that I champion first and foremost the philosophical method over and above any particular view that has come from it.” I agree that philosophical method should be used as a means for progress, but I don’t believe the method itself is value-free or neutral. On the contrary, I think that philosophical method and the subjects we choose to examine with the method are already biased, even if for good reason.

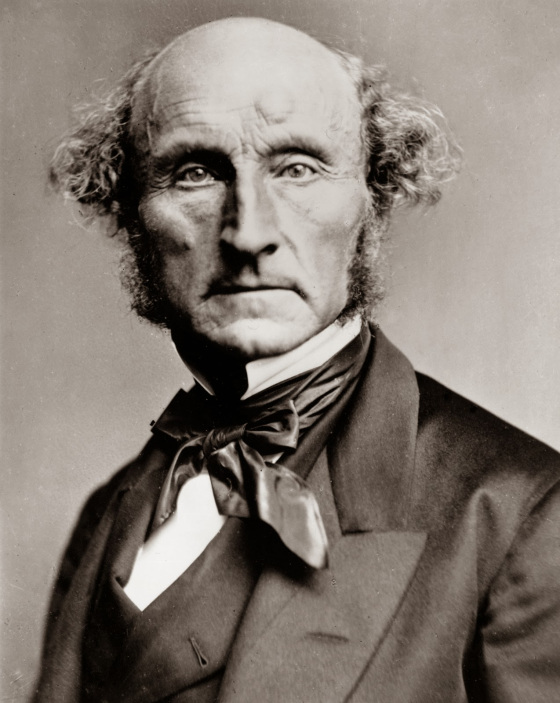

Most of us who teach philosophy, I would venture to guess, have adopted classroom discussion guidelines that are similar to the ones described by Courtland. Most of us, I trust, have been trained to emphasize the role of reasoning over opining in the construction of arguments, to temporarily suspend judgment to weigh evidence, and to have a basic requirement of civility. I do this because I share John Stuart Mill’s optimistic attitude that “wrong opinions and practices gradually yield to fact and argument.” Also like Mill, I don’t believe that the argumentative methods of philosophy alone can prompt us to revise our erroneous thinking, but rather “discussion and experience” and further discussion “to show how experience is to be interpreted” are all added together in a complex recipe of genuine and lasting persuasion. Argumentation is but one ingredient along with human relationships, values, identities, our historical circumstances and systems, and our understanding of these things.

The central and difficult issue Courtland presents in his response to me has to do with our freedom and responsibility to examine all views. The position Courtland presents, via Mill, is two-fold: 1) if someone holds the correct view and it goes unchallenged, then the view is in danger of becoming dead dogma, and 2) if someone holds the wrong view and it goes unchallenged, then the view cannot be revised. I am certainly not opposed to challenging views, since I agree that is the business of philosophy. However, I am opposed to challenging views just for the sake of challenging them alone without the exercise of proper judgment and an understanding of people and their intentions for participating in discussion in the first place.

In the case of someone who may hold the right view, I wonder, contra Mill, whether it is really possible or desirable to maintain a completely unsettled stance about everything at all times. It is one thing to honestly acknowledge our propensity for error; it is another to hang all ideas in equal suspension of doubt, particularly when our actions and other beliefs need some ideas to be held with some sort of solidity. In other words, can I acknowledge my fallibility (i.e. that I may be wrong about what I think and so constantly must be willing to change my mind) and my finitude (i.e. that I must believe and do stuff here and now) at the same time? Why does the correctness of a view have to be constantly won, when other views I hold are in more urgent need of testing? Furthermore, some things do seem to be more settled because they don’t inspire much serious debate or even seem like viable questions to discuss in the first place. If everything is really to be on the table for conversation, it seems that some topics never get to the table because they are so settled. For example, the view that white, land-owning males should have the right to vote in the United States has a historical basis, but over time has calcified in such a way that it has become a non-issue. But other issues, like equitable pay for the same tasks by women or minorities, are left open for more consideration. The issues we choose to discuss and challenge provide yet another way in which we are already including and excluding certain kinds of discourse.

There really is no shortcut through this strenuous and rewarding process of changing one’s mind. If philosophical method is to have any value, I believe it has to be connected with the purpose of philosophy—and maybe this is where our conversation could proceed next.

Dr. Sergia Hay is SOPHIA’s Membership and Chapter Development Officer and is Assistant Professor of Philosophy at Pacific Lutheran University. She is representing only her own point of view in this essay. For more information about Dr. Hay, visit her profile page in SOPHIA’s Directory.