The audio quality gets better in the next two episodes following this one, as we start here with not the best online voice quality. Feedback has been good so far nonetheless, so please bear with us as we philosophers are learning. Enjoy a fun conversation with a lively philosopher who after Episode 1 serves as co-host for the show.

(1 hr 8 mins)

Click here for a list of all the episodes of Philosophy Bakes Bread.

Subscribe to the podcast!

We’re on iTunes and Google Play, and we’ve got a regular RSS feed too!

Notes

- In the episode, we spoke vaguely about the scandalous essay that purported to find a connection between autism and vaccinations. As we noted on the show, the piece was retracted. You can read about that retraction here on CNN: “Retracted autism study an ‘elaborate fraud,’ British journal finds.“

- We also talked about the uncontroversial fact that the average global temperature is rising. There are various debates about what to do and to say about how to combat climate change, but the science is clear that we’re getting warmer, overall. Here’s a simple site from NASA that makes it clear: “Global Temperatures.”

You Tell Me!

For our future “You Tell Me!” segments, Dr. Cashio proposed the following question in this episode, for which we invite your feedback:

- “What idea or belief do you have that has changed from an enlightening experience?”

What do you think? Let us know! Twitter, Facebook, Email, or by commenting here below!

Transcript

Transcribed by Drake Boling, June 7, 2017.

For those interested, here’s how to cite this transcript or episode for academic or professional purposes (for pagination, refer to the printable Adobe PDF version of the transcript):

Weber, Eric Thomas and Anthony Cashio, “The Molemen and Plato’s Cave Today,” Philosophy Bakes Bread, Transcribed by Drake Boling, WRFL Lexington 88.1 FM, Lexington, KY, January 9, 2017.

Dr. Weber: Hey, you’re listening to WRFL Lexington, 88.1 radio. This is Dr. Eric Thomas Weber at the University of Kentucky and you’ll soon hear Dr. Anthony Cashio of the University of Virginia at Wise join me for a talk show. Our show is called Philosophy Bakes Bread: food for thought about life and leadership, a production of the Society of Philosophers in America (SOPHIA). Our first episode is airing today, Monday, January 9th, 2PM Eastern time here in Lexington, Kentucky, and we’ll be on each Monday for the spring semester of 2017. If you’re out of town or across the globe, you can stream the show live at WRFL.fm/stream. If you unintentionally miss an episode, you can subscribe to the show once it is subsequently distributed as a podcast soon after airing. Don’t miss a beat. The easiest way to keep track of us is on SOPHIA’s webpage for the show: philosophersinamerica.com/philosophy-bakes-bread.[1]

Today’s show is our first official episode airing in its present form on radio then as podcast, four pilot episodes created in 2015 and 2016 preceded this one and can be found at philosophybakesbread.com. The name and idea for this show come from an old saying, “Philosophy bakes no bread.” It can sound dismissive of the value of philosophy, although in one version of the saying, the poet Novalis said the full phrase read as follows: “Philosophy can bake no bread, but she can procure for us God, freedom, immortality. Which, then, is more practical–philosophy or economy?” Sadly, the more famous part of the phrase is the first half, and I’ve got a clip for you from John Cleese replying to the old quip in a recording produced for the centennial celebration of the American Philosophical Association, which was in the year 2000.

(Begin recorded clip)

Announcer: Some thoughts from John Cleese:

John Cleese: It has been said that philosophy bakes no bread. You may think it hard to figure out, just what philosophy is good for. Is it just argument, or speculation or a required course in college? Well, here is a thought: philosophy is fun. Like skiing down a sheer cliff, or singing a difficult song. Philosophy can fill you with the edgy excitement that makes being human rather wonderful. You don’t believe it? Then I suggest you seek out a philosopher and find out just what you’re missing, because philosophy may bake no bread, but the thoughts it provides can make the meal of life more satisfying.

Announcer: A message from the Philosophers of America celebrating 100 years of thought.

Dr. Weber: That’s the famous line that we hear about from John Cleese. In Philosophy Bakes Bread, this radio program, we aim to buck the misleading outlook that some hold about philosophy and to showcase myriad ways in which philosophy most certainly does metaphorically bake bread. Today’s first radio broadcast will feature a special introduction interviewing a guest who will hereafter be a co-host for this show, Dr. Anthony Cashio. Before I get too far here, let me play you the little musical intro.

(musical intro)

(theme song)

Announcer: This podcast is brought to you by WRFL: Radio Free Lexington. Find us online at wrfl.fm. Catch us on your FM radio while you’re in central Kentucky at 88.1 FM, all the way to the left. Thank you for listening, and please be sure to subscribe.

Dr. Weber: Anthony Cashio is assistant professor of philosophy at the University of Virginia’s college at Wise, Virginia. He earned his bachelor’s degree from Birmingham Southern College and obtained a PHD in Philosophy from Southern Illinois University Carbondale. His work is focused on issues of social justice, the role of value systems in problem solving, the relationship between history and value structure, the nature of non-violence, and the role of the environment as a social institution. Anthony is also fiercely dedicated to teaching, both in and out of the classroom. His passion and his dedication was recognized with two major awards both issued in 2016, one from students and the other from fellow faculty members. He received the Student Government Association’s Professor of the Year Award in 2016, as well as the faculty-nominated Outstanding Teaching Award. When not in the classroom or discussing philosophy and politics at the local pub, Anthony can be found at Wise, Virginia spending time with his wife Miranda and his two children Madeline and Chappelle. They enjoy hiking, camping, and generally rambling among the beautiful mountains in Southwest Virginia.

Before we jump into discussion with Anthony, I should tell you about how you can get a hold of us with comments, questions, praise, answers to questions we ask you, and so forth. We hope that you will reach out to us with any of the topics that we raise on the show, or on topics that you want us to bring up. Plus, we have a segment called “You Tell Me!”. Listen for the question that we will raise for you today, and let us know what you think. You can reach us in a number of ways. For instance, we are on twitter as @PhilosophyBB, which stands for Philosophy Bakes Bread. We’re also on Facebook at Philosophy Bakes Bread. Check out SOPHIA’s Facebook page while you’re there, Philosophers in America. You can also of course, also email us at philosophybakesbread@gmail.com, and you can call us and leave a short, recorded message with a question, or a comment that we may be able to play on the show at 859-257-1849. That number is 859-257-1849. If you’re interested in learning more about SOPHIA, check us out online at philosophersinamerica.com. What follows are four pre-recorded interview segments to which we’ve added a couple of light-hearted, special segments as well. I hope you enjoy this first episode on WRFL Lexington and that you reach out to us. Today’s episode is about Molemen and Plato’s Cave Today.

Dr. Weber: Hey everybody. Welcome to Philosophy Bakes Bread: food for thought about life and leadership. This is Dr. Eric Thomas Weber at the University of Kentucky. I’m talking with Dr. Anthony Cashio at the University of Virginia at Wise. He is a very wise person at Wise. I want to ask him to introduce himself to us, and to tell us about why people should care about philosophy. What is this? Tell us about yourself before we then jump into talking about Plato. Then in the spirit of what we’re going to be talking about with regard to Plato, remember that incredibly important dictum, “Know Thyself!” So I ask you, Dr. Cashio, to tell us about your knowledge of yourself.

Dr. Cashio: That’s a bit of a challenge. How well do I know myself? I think I got into philosophy like most people who do philosophy: for the parties!

(laughter)

Dr. Weber: For the money!

Dr. Cashio: For the women and the power and the drugs and the money. Isn’t that why we all got into philosophy? The rock and roll lifestyle. (laughter) That’s how I sell it to my students. I was like, “Do you want people to love you? Make a lot of money? Do philosophy.” No, but seriously. Philosophy is the art of being a human being. I get that from Michel de Montaigne, that’s his quote. The art of being a human being. All arts have some sort of end, some purpose. The study of philosophy is the study of and reflection upon what it means to be a human being living and struggling and doing your best in the world, in its broadest sense. It is asking questions, and it is asking deeper fundamental questions about life, about meaning, about truth. It comes off very pretentious, but I think it is a very practical discipline as well.

Dr. Weber: If it seems pretentious, how do you see it actually being related to real life and everyday people out there who are listening?

Dr. Cashio: By knowing thyself. It’s an act of self-reflection. Being able to orient yourself in the world, being able to live intentionally. Being able to be aware of your biases, of your fears, your emotions, the thoughts that you have. Being able to have more cognizant conversations with others, and being able to learn from other people better. The study of philosophy opens up your world. It teaches you how to be humble without falling into self-doubt.

Dr. Weber: Don’t people already know themselves? What do they know better than themselves? You say that philosophy is going to help us to know myself. Don’t I know myself?

Dr. Cashio: I wish that were true. If someone asks you a question like “Why do you do philosophy?” you see how well you know yourself. I think that most people think that they know themselves but they don’t. Or they could know themselves better. Or they don’t realize that knowing themselves also means knowing the world in which they live and the people that they spend time with and the members of their community and their place in their community.

Dr. Weber: What is an example of someone suffering from not knowing him or herself? Who doesn’t know him or herself? We have go listeners in Kentucky, and then once this becomes a podcast we have listeners around the world, hopefully. Who out there needs to hear this and might suffer and in what way from not knowing themselves? Why do they need to be listening to this philosophy stuff? I like philosophy, but I like that question anyway. Why should anybody be listening? Asking that question, I think keeps us on track.

Dr. Cashio: That’s a hard question, Eric. To answer it, you have to know yourself a little bit better.

Dr. Weber: You can also look at people who have been unhappy and think about the extent to which maybe…

Dr. Cashio: I’ll give you an example from my own life. I was complaining to my wife about something the other day, about my son. I was saying that I was hard on him sometimes about some subject matter, because I don’t want him to end up like me. And my wife looks at me and goes, “Like what? Someone who has a job and a career that they love? Who has a family that loves and adores him, who has friends all over the place? Who gets to do philosophy everyday, something that he loves and enjoys?” And I was like “Oh.” My wife is significantly wiser than I am.

Dr. Weber: She loves you too, for some reason. I’m not sure what it is.

Dr. Cashio: Exactly. For some reason. Knowing yourself is also about realizing the good that’s in your life and being aware of that. A lot of the people that suffer are not good at that. Knowing yourself is a call to be aware of your own faults. But also to be aware of the goodness in your life and I can’t think of anyone who doesn’t have that problem.

Dr. Weber: That’s an interesting point. OK, well what about folks who think they know what’s going to make themselves happy, but man are they wrong about it?

Dr. Cashio: That’s kind of the concern, right? What does Socrates say in The Apology: “You think these people make you think you are happy, but I really make you happy by asking you all of these annoying questions. I make you think about these deep, reflective things, which is why you’re going to kill me. The athlete over there makes you feel good about yourselves, but I am the one that makes you actually happy. Of course, he dies for that answer.

Dr. Weber: He died for us in a way. This is one of the martyrs of our world. I think the modern version of this is the mid-life crisis. People work their whole lives, they get their degree, they marry someone in a certain way, they get the kind of house that they have always thought that they want, they get the kind of cars that they want and so on. They have their kids in the right kinds of schools. Then some people who seem to have it all are just absolutely miserable. Never having actually done those things that would make them happy, they are doing things that they always thought would make them happy, or other people told them would make them happy. They end up absolutely miserable, surrounded by wealth and splendor and good fortune. Yet they are miserable because they weren’t true to themselves.

Dr. Cashio: Are you having a mid-life crisis, Eric?

Dr. Weber: No, despite a number of things I think I’m profoundly happy. But I know a lot of people who are absolutely miserable in circumstances that others would kill for. They would just be…they seem to have everything, yet they are miserable. Part of it is what you said about not seeing all that you have to be grateful for. But there is another part which is that if you are not true to yourself, which is where we started, if you are not true to yourself, you may make a lot of money as an engineer, but Lord, you always wanted to be a history teacher. You would have been happy as can be in that position. You would have made less money, but being incredibly happy every day is a pretty huge reward.

Dr. Cashio: I think you’re right. It’s such a common and profoundly simple idea, the idea is almost cliché, of the midlife crisis. And yet, it seems to be really really important, if it’s so cliché and it’s so obvious, we keep teaching it, and we keep doing it over and over again. This is where philosophy comes in. It’s sort of like yeah, actually knowing thyself is both very simple and a very difficult task. Being comfortable.

Dr. Weber: Talking about simple things that are hard to do, losing weight is something that so many Americans, myself included, need to do. It’s obvious what you have got to do. You should eat this many calories a day and not more. You should exercise. OK great. Why is this so hard to do? It is very hard to do simple things sometimes. It’s hard to get ourselves to do certain things. This know thyself idea, I think there’s so many people that go through it. Part of the problem is that there is a cycle, but each new person hasn’t been through it yet. That’s why this philosophical education can seem so important.

Dr. Cashio: Yes, and I think this is why people get interested in philosophy. Everyone has gone through it before, and you see people have gone through it before, so you go “Oh, what have they gone through, because they are going through what I went through.” but you don’t couch it that way when you are an 18 year-old jerk. You think “Oh, I am having an experience that no one else has had in the world.” We don’t realize that everyone has had this experience in the world.

Dr. Weber: Have you heard the line about the quarter-life crisis? Have you heard of that?

Dr. Cashio: Oh yeah, I’m pretty sure I had a quarter-life crisis.

Dr. Weber: OK, tell us about your quarter-life crisis. This is knowing thyself, it’s important. It’s getting to know Dr. Anthony Cashio and his discovery of philosophy and of himself. Tell us about your quarter-life crisis if you’re willing.

Dr. Cashio: Oh, I don’t know if I’m willing.

Dr. Weber: Tell us about the phenomenon, then, of the quarter-life crisis.

Dr. Cashio: It’s the same problem as the midlife crisis. It just comes earlier, which is almost a blessed thing. You realize, “Hey, I’m not happy with the direction that my life is going.” It’s for people who can almost anticipate what they’re going to be in their mid-life. Like, “If I keep doing this by the time that I get to my mid-life, well I’m planning a crisis.” then you realize Why do I have to plan the crisis ahead of time? It was probably when I was in graduate school, working on my dissertation, wondering “Is this is what it is all about? Is this what I want to do?” Anyone who has written a dissertation knows that at a certain point in the writing of your dissertation, you probably will hate it. I might be wrong about that, maybe it was a unique experience to me. But at some point you’re like “If I have to think about this thing one more time…and I’m wrong and I’m stupid. Will I be able to get a job? Maybe I should have gone to law school after all. Maybe I’ll just sell out hard and go on. I’m overweight and I’m not happy about it. This is a path I don’t want to be on.”

Dr. Weber: It’s better to learn it early, but at the same time, quarter-life means for most people that you’re already through college and maybe even through some grad school and you’re on a path, “Oh hell, am I on the right path?” You’ve invested so much. That’s why it’s a crisis at that point. It’s better to learn it then than so much later in life, I suppose.

Dr. Cashio: Better at 25 rather than 50.

Dr Weber: This is one of the things that philosophy can contribute. We’re going to talk about Plato’s cave and the shadows on the wall that make us think that we have to have the picket fences and the 6,000 feet home and…

Dr. Cashio: That’s how I got out of the crisis, believe it or not. Looking at it and going, “Wait a minute, those things that I feel miserable about, I don’t have to. I do have a good life, and I actually do enjoy the things that I think about and I’m able to be more in the present and to not want these things.

Dr. Weber: Thank you so much, Dr. Cashio. We’re going to come back in just a little bit and talk about the allegory of the cave in Plato’s Republic. So keep listening to WRFL Lexington. This is Philosophy Bakes Bread: food for thought about life and leadership, a production of the Society of the Philosophers in America.

Dr. Weber: Hey everybody. Like I said, we’re here with Dr. Anthony Cashio, assistant professor of philosophy at the University of Virginia at Wise, a very wise man here to talk with us. He has recently been teaching Plato’s Republic. I was wondering if you could tell us a little bit about the allegory of the cave, because I have a question I want to follow up with about that. I think people may need a refresher, or some folks haven’t ever heard of the allegory of the cave. Could you tell us a little bit about how you understand that allegory, that analogy from Plato?

Dr. Cashio: Plato is telling this story right in the middle of The Republic, they have just spent several chapters discussing what justice is, building the perfect city, and they have gotten to this part in their discussion, Socrates and his interlocutors have decided that the perfect city would have the wisest ruler. The question becomes: How do you train these wise rulers, these philosopher kings to lead? Socrates begins telling a story about, imagine that there are several prisoners. They are chained down in a cave, and their heads are locked in and they can only see the wall right in front of them. Behind them, there is a fire going, they don’t see it but there are these short little men carrying statues in front of the fire.

So, of course, everyone who is chained down can only see the wall in front of them, and all they see is the shadows on the wall. They see the shadows on the wall and they talk about the shadows on the wall, and they debate about the shadows on the wall. One of them is like “This is a tree. We’re going to call this tree an oak!” and then another goes “That’s not an oak tree, this is an oak tree!” They fight about it and they argue about it and they are really, they don’t know it, but they are arguing about shadows on the wall. One day, some of the chains on one of the prisoners becomes rusty and breaks off. He turns around and he looks back and he sees the fire right there. I don’t know if you’ve ever done this, maybe when you’re young and stupid. You ever shine a flashlight in your eye?

Dr. Weber: Yes, I have.

Dr. Cashio: Yes, everyone has done that. So, it blinds you, and you’re kind of shocked, and you’re disoriented and you can’t really tell what’s going on. This is what happens to our prisoner who is escaping, he gets turned around and he sees this fire and he’s blind. Eventually his eyes adjust. He sees these strange little men carrying statues, and he’s like, “Woah, I thought that was a tree, but That is a tree!” He is so amazed, he’s like, “Dude, this is amazing.” He turns back and he sees some light even beyond the fire, and so he goes towards that light, and he begins working his way out of the cave, slowly but surely. He doesn’t realize he’s in a cave, but he keeps following his way towards the light and it’s this long, hard path. He keeps slipping, he keeps falling, he keeps scratching his knees. Eventually, he comes outside into the world and the sun is shining and the sky is blue and is bright and there are birds singing and there are real trees, and he’s like “What is that?”

Dr. Weber: Real oak trees.

Dr. Cashio: Green, pretty little trees. Of course, he’s blind and he’s disoriented, but eventually his eyes adjust and he begins to see things for what they really are. He realizes that these are real trees, these are real objects and that what was going on inside the cave was that people were arguing about facsimiles of facsimiles, about shadows that were fakes of the real thing. Finally, his eyes adjust and he realized that everything in the world exists because of the sun and because it is bright and it is beautiful, and he is like “This is amazing”. But this is where the story gets really interesting to me. He is a king, he is not just a philosopher. He is not just out in the world thinking about the forms and the ideas and these beautiful things. He thinks “I have got to go back into the cave.”

Dr. Weber: His friends are back there.

Dr. Cashio: His friends are back there! He’s like, “I gotta show him this, I gotta show Stand how wrong he was. He thought that shadow was an oak tree. We were both wrong. This is an oak tree.” So he goes back in the cave. Now, if you’ve ever gone to a movie in the afternoon when it’s bright and sunny outside, you go to get some popcorn and your eyes adjust and it’s all bright and you go back inside and you’re like “Where am I?”

Dr. Weber: Just the other day I walked in with a big thing of popcorn into the movie theater. My eyes hadn’t adjusted and I stumbled on a little step that I didn’t know was there and it was literally like one of those movies where I had popcorn go everywhere into the world. It blew up like it was planned, an explosion.

Dr. Cashio: Everyone was probably like, “Oh you idiot”.

Dr. Weber: It was pretty funny. It must have been funny to others.

Dr. Cashio: Everyone was probably like “Shut up, we’re trying to watch the movie!”, and you’re kind of sneaking around, like “Do I give them the crotch, do I give them the butt? How do I get past these people to my seat? Then you sit down next to the wrong person, and everyone thinks you’re ridiculous but your eyes just haven’t adjusted to the dark again, because you were out there in the real world and they are watching shadows on the screen. It’s the same way for the philosopher or the prisoner when he goes back in the cave. He goes up to his friends like “Guys, this isn’t real. It’s out this way. You gotta come with me.”

Dr. Weber: And are they receptive of this message? Do they greet him thankfully?

Dr. Cashio: They think he is an idiot! He’s stumbling around, they’re like “You’re making it up!” Sometimes they’ll get so angry they will kill him. This is Plato’s allusion to Socrates here.

Dr. Weber: They don’t want to be pulled from their movie.

Dr. Cashio: The movie is entertaining. They don’t want to go to the real world. The real world is cold. They don’t even know what the real world is. They think this is the real world, they’re arguing about shadows. Eventually, he gets someone to turn around, he gets the chains off. He gets one person to turn around and they turn around and of course they are blind and they are like “What are you doing to me? Why would you shine a flashlight in my eye, you jerk?” But their eyes adjust and they go “Now I see”, and then you go “Come this way.” The prisoner then drags his friend out of the cave, and the dragging and kicking and screaming, going up the slope and it’s rough and it’s hard. But eventually you come out and you get your friend out into the sun and they are like “AAH I’m blind.” because, basically they are mole men. Your eyes adjust and sees the beauty of the world and he goes “Oh you’re right”. Now you can really do philosophy, because now you can actually study the things around you as they really are.

Dr. Weber: And you can talk to each other about it now.

Dr. Cashio: You can talk to each other about it, and the more you talk to each other the more you can learn about the things that you are seeing. And it’s beautiful and amazing. Plato’s point with this ties into education and also his theory about truth and metaphysics. But education, for Plato, is the turning around of the soul. Everyone wants to talk about what is real. Everyone wants to talk about what is good and what is true and what is right. But they are arguing about shadows. They are arguing about memes that they read on Facebook. They are arguing about twitters…tweets. But real education is when we turn around the soul. It’s not an easy process, it’s not like we turn around and we see the truth and we go “Oh, it’s a great enlightening, mystical experience.” No. It’s a long, hard, ugly climb out of the cave.

Dr. Weber: It’s uncomfortable.

Dr. Cashio: It’s long and you’re scraping your knees and you make mistakes and you get up there and your reward is that you see the truth, but…no one will believe you when you start telling them, because you sound like an absolute idiot.

Dr. Weber: You’re stumbling and throwing your popcorn everywhere.

Dr. Cashio: Yeah, you come in, you trip, you drop your popcorn and people laugh and you’re like “No, I could just see better than you.”

Dr. Weber: People are very comfortable watching movies. They don’t want to be dragged out in the middle of a movie. I think the point you made, which is exactly right, shouldn’t be ignored, which is that Plato said that they might want to kill you for disrupting their comfort. He didn’t mean that lightly, because he knew, it’s thought that The Republic was written after Socrates’ death.

Dr. Cashio: It’s no arbitrary concern for Plato. His teacher was killed for this very reason.

Dr. Weber: One of the reasons that I wanted to bring up this allegory of the cave, was that as you say, everybody seems to think that they are looking at the truth, and yet so few people are reflective enough. The word enlightenment is usually reserved for much later on in intellectual history, but Hilary Putnam says that the first enlightenment, in his eyes, was with Socrates. The enlightenment means the turning towards the light, the turning around from the shadows to look at the fire behind them in the cave. That enlightenment is so crucial a step, and at the same time we have so many people today, all of whom think that everyone else is looking at shadows but not themselves.

Dr. Cashio: That’s kind of the characteristic of shadow-fighting, arguing about shadows. You’re like, “No, you’re not talking about the real thing. My shadow is the real one.”

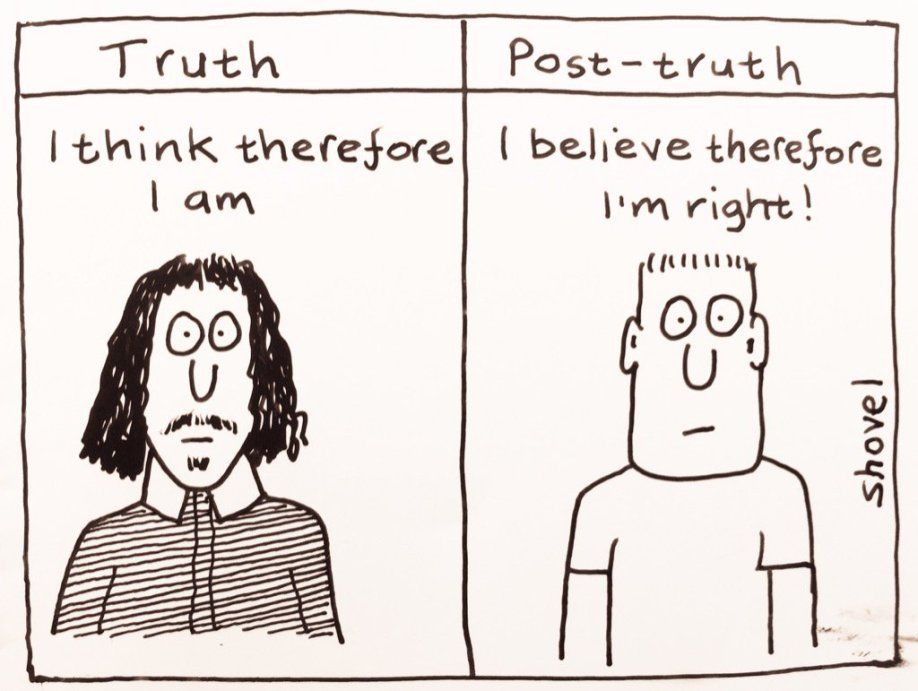

Dr. Weber: It’s funny because the analogy is so easy to witness when you talk to children. You and I both have children, and my son, when we’re driving, he’ll see a rabbit in the clouds. Any adult knows that he’s not actually seeing a rabbit, but darn it if that cloud doesn’t look quite a bit like a rabbit sometimes. Yet people on Facebook and with their tweets as you say, they think that they are seeing the rabbit. They think that they are seeing something real in a cloud without really digging deeper, without turning their heads and so forth. In our democratic society, everybody thinks that each other is looking at shadows. We’re aware of this metaphor, but it’s so pervasive that everybody else is looking at shadows that even recently this political representative was saying that there are no facts.

Dr. Cashio: The post-fact world. What a nice world to live in. Makes it very easy to do our job. You can just say whatever you want.

Dr. Weber: It’s terrifying in a way. We’re going to need to talk in another segment about what to say about this. Should we be like Plato and think that there is this absolute truth and so forth, because one doesn’t necessarily have to agree with him on some of those points.

Dr. Cashio: No, you don’t. I do like the idea that the education plays out. Like, everyone wants this truth or some kind of truth. But education is not like pouring water into an empty cup. It’s already there, we already have it. We have the capabilities for it and we have the drive for it. Education is literally just finding the way to point someone in the right direction. The debate becomes what the right direction is.

Dr. Weber: When we come back, we’re going to talk a little bit about this metaphor and think about Is it the case that there is some ultimate reality and somehow everyone is out of touch with it? Or should we think that there is no reality? Or maybe ideally we can think about some place in between that is a little bit more moderate and reasonable. Thank you so much to Dr. Anthony Cashio here for giving us a little bit of the story of the allegory of Plato’s cave. We’ll be back in just a little bit.

Dr. Weber: Welcome back to Philosophy Bakes Bread. This is Dr. Eric Thomas Weber and I’m here talking with Dr. Anthony Cashio of UVA Wise. We were talking in the last segment about Plato’s allegory of the cave and the fact that people need to turn around in the cave to see that what we are used to seeing and used to thinking about and obsessing about are false shadows on the wall that are shadows of some object behind us that people manipulate to get us to think this way or that way. It’s amazing how much it is really a metaphor for how people think about the media today. People complain all the time about the media. The media is that fireplace behind us in the cave where folks are showing us symbols and we’re worried about being manipulated. The philosopher, as Dr. Cashio was explaining, goes all the way outside the cave and realizes that the real world is more beautiful and amazing and complex beyond there. I wanted to talk with him about the fact that recently we have had certain political representatives saying that there are no facts in politics anymore. If there are no facts, there are no lies, right?

Dr. Cashio: That’s the anti-Plato. Opposite of Plato to the extreme.

Dr. Weber: The extreme opposite of Plato, the idea that there is no real world outside the cave, that everything is only shadows, says that point of view. Well, I wanted to talk with Dr. Cashio about how we see that extreme. We can either think perhaps that there’s this absolute truth like Plato thinks, and that it’s real-world outside the cave that’s unchanging forms and we don’t need to go into the details about that. The point is that there is this absolute truth and real world that everybody seems to be wrong about unless they are looking at the pure truth in the sun outside the cave. Or we can think that there are no facts, that it’s all just cave. The question is: Is there a middle ground we can hold instead of those? Or should we just be absolutists? Or should we be nihilists and relativists who think that there is no truth and so forth? What are some examples about how that question plays out in real life for us? In the real world of philosophy baking bread, let’s think about how these kinds of questions impact us for real. Dr. Cashio, are those the only two options?

Dr. Cashio: I hope not.

Dr. Weber: Why not? Why not be absolutists about the truth?

Dr. Cashio: There is a certain falliblism to it, I think that’s how we can approach it,

Dr. Weber: What is fallibilism?

Dr. Cashio: How do we know when we have the truth when we have the truth? It’s a problem about knowledge. Say we take Plato’s truth, and we assert I have the absolute truth. Then my neighbor comes along and goes, “No, no no. I have the absolute truth.” That’s how wars are started. People die over these kind of arguments. It’s dangerous, and it seems to be disingenuous to how we get out. It could be the case that there’s multiple ways out of the cave, to stick with the analogy. That we can work our way out. But at the same time, it’s not that there is no truth. There are facts, sometimes they are uncomfortable. We have to deal with them. The climate is changing.

Dr. Weber: Let me come back. The idea that there are multiple ways out of the cave, in other words, you can take different steps, you can hold onto this side of the cave wall or that side of the cave wall and your experience can be different as you go and pursue truth. Is that part of what you are saying?

Dr. Cashio: That’s part of what I’m saying. There is different ways out of the cave, different paths. You might be an empiricist, someone else might be studying experience to get out of the cave. Someone else might think that the best way out of the cave is a rational study of mathematics. Someone else thinks that the best way out of the cave is practical education. It could be the case that they are all correct, that they all get you there.

Dr. Weber: So there are multiple paths. Here is another element to what you’re getting at. Even when multiple people get outside of the cave, they don’t all see from exactly the same perspective when they look at the tree. The tree may be truth and so on, and the light of the sun giving us the ability to see that. But even so, when we are trying to understand that truth, we are nevertheless even still seeing it from different perspectives. Though there, at least, we are looking at the real deal.

Dr. Cashio: Yes, I think we can go with that. But be careful there, because then you are indicating that there is an absolute truth.

Dr. Weber: This is the question about whether or not we should be thinking there are no facts, or that there’s absolute truth. This is one way of thinking about an intermediary ground. Even if you’ve got multiple people looking at the truth, they may never, each individual grasp all of it. You were saying an example of “I have the truth,” in this case let’s say that someone understands how gravity functions. Then we learn more about force and we learn more about the fact that the mass of the Earth matters as far as our gravitational pull. You might think that gravity is the same on the moon, but it’s not. You can learn more, even though you’ve gotten closer to the truth with one effort, you can always learn more, is I think part of the way of thinking about it.

Dr. Cashio: So truth is an ongoing project. I like that idea.

Dr. Weber: So what are two real world examples? We’ve been talking about this metaphor and allegories. How do we see this in real life? I mentioned the news, but what are some other concrete life examples? You and I have talked in the past about this. Where do people think about this falsehood, or it’s just whatever you think, man, or this is just your agenda? What are a couple examples for people in real life?

Dr. Cashio: The vaccination argument, the debate makes a good one to think about. You have two sides. One says vaccinations are OK, and we have the facts and science to back it up. On the other side, the anti-vaccination movement.

Dr. Weber: Not that vaccinations are just OK, they should be obligatory, people think.

Dr. Cashio: Yes. Where do you stand on that?

Dr. Weber: I was just living in the state of Mississippi for the last 9 years. You think of Mississippi as a state that wants small government. It’s the state with the highest proportion of vaccinations in the whole country. The largest proportion of people who are vaccinated in a state is the state of Mississippi, they are the ones that do it most pervasively, and it’s hardest to get any exceptions. So vaccinations are things for which there are very rare exceptions in which your medical condition can mean that it’s a bad thing or a dangerous thing for you to get vaccinations, but it is ultra rare. So people thinking that their kid shouldn’t have it almost always are wrong, probably, about the risks. But sometimes there may be some strange exceptions. So the law does allow for some rare exceptions. Bu the idea is that if you don’t vaccinate kids, you get people dying of diseases that we should have eradicated. In the state of California, there was a measles outbreak. We shouldn’t have measles. We shouldn’t be dying of polio anymore. We shouldn’t have those kinds of problems anymore. vaccinations can stop those. That’s an example of, I like that example because some people think that folks on the right criticize science a lot and are anti-science. Well a lot of people on the left seems to be anti-vaccination. It’s nice to point out that people on the right and people on the left can be anti-science sometimes.

Dr. Cashio: We tend to pick our things to put our blinders on about. We’re just like, “This is my shadow, I’m going to stick with this.” But vaccination, the anti-vaccination movement has always fascinated me because the evidence is so strongly there in favor of vaccinations. If I could save a child from dying from measles, why wouldn’t I do that? It seems very obvious to me, but, that’s part of my shadow. How do they end up thinking in this way about the anti-vaccination movement?

Dr. Weber: The Jenny McCarthy phenomenon is worth mentioning.

Dr. Cashio: Indeed. Fear. Jenny McCarthy basically suggested, I hate to pick on her, but, that vaccinations cause autism. That’s the fear. This is my understanding. Does that seem correct to you?

Dr. Weber: There were suggestions and pieces that have been retracted, that there might be a connection. By pieces, I’m pretty sure there was one piece, I don’t know how many, but I think there was at least just one published piece that was retracted because it wasn’t done properly or the findings weren’t replicable and so forth. Anyway, the point is that the science is overwhelmingly clear that there is no connection between autism and vaccinations. But the mere suggestion that there might be, made Jenny McCarthy made some famous people who can get attention easily and have children with autism and they wish they had a solution. I know what it’s like to wish one had a solution for a child’s illness. Any parent who has had a sick kid knows that. But all of a sudden to suggest that all science is shadows on the wall because I want to believe that there is this thing that I can blame, or solution that I might be able to find that isn’t really there, that is what’s tragic and terrifying. The problem is of course that famous person can make this falsehood the biggest shadow on the wall everybody can’t help but see. Then you have to work so hard to get people to understand the truth of the matter. It’s like that line from, I think it was from Mark Twain, that a lie can get around the world several times before the truth has gotten its socks on.

Dr. Cashio: Oh Mark.

Dr. Weber: This is Weber’s paraphrase, an inelegant paraphrase.

Dr. Cashio: You’re right, there’s something about the fear of it as well. You’re a new parent, you’ve got a newborn and you want to do everything in the world to protect them. Someone comes along and says that this thing, these giant corporations are telling you they will protect your child, but it won’t. It will give it autism, it will make your child sick. You want to protect your child. So you think, well I don’t want to risk my child’s life, and these people just want to make money, and they are willing to abuse my child just to make money. So of course I am not going to vaccinate him. Because it’s unnatural and it will make him sick. There’s this fear instinct, there’s this protective instinct, and it’s kicking in and it overrides it. Would you risk the life of your child over something that was just a shadow?

Dr. Weber: This is the thing. The doctor who comes in to try and explain is the person who is having a hard time seeing in the darkness, and there’s popcorn flying everywhere because he can’t see those little steps. So everyone thinks “What do you know? I’m going to go to another doctor and another doctor until I find someone who confirms what I say. We want the right people behind us holding the statues up so that we see the statues that we want to see on the wall. The other example that you mentioned briefly in passing, climate change. It’s undeniable that the average global temperatures are going up. At the same time, though, there are folks who are worried about people who have agendas, who want you and I to believe this or that about the climate so that you can impose upon business or what have you. You’re just another person holding a statue on the wall to manipulate people. What is your experience thinking about the climate change issue?

Dr. Cashio: I live in the middle of coal country. Wise County and its surrounding counties, coal is the business, or was, which is another whole issue. The concern really is financial. The government is coming in and putting these regulations based on these sciences that, why believe them anyway? We’re losing our jobs, we’re going hungry, the business that has made this area great is now going away, and so the greatness of the area is going away. It doesn’t take much to see the poverty caused by the coal mines shutting down.

Dr. Weber: I live in Kentucky right now, and let me tell you, Kentuckians are aware of this issue too.

Dr. Cashio: It is very much on people’s minds. You’re coming along telling me this climate change, but my immediate experience is that coal, obviously one of the main fossil fuels, is life. It’s not death. I don’t know if you have them in Kentucky, but around here everyone drives around with these bumper stickers that say “friends of coal”.

Dr. Weber: We have those too.

Dr. Cashio: You can get black license plates that say “friends of coal”. It’s a big idea around here, that the government and the dirty liberal agenda pushing this idea of climate change is really just trying to destroy our livelihood. We have this idea of fear, we have this need for protecting yourself, protecting your family and protecting your career that clouds this idea about climate change.

Dr. Weber: This is why we kill the philosopher who comes on in to tell us we gotta let go of the shadows that we’re looking at. We have strong, powerful interests.

Dr. Cashio: I teach an environmental ethics class here in coal country, so I tread the line kind of carefully. I was at Wal-Mart the other day, this big store. There was this truck and it was, I’m trying to remember what the bumper sticker said…it said “Save a coal miner, kill a tree-hugger”. Kill a tree-hugger. I was like Oh! This person advocates murdering people

Dr. Cashio: You can’t get a better example of what Plato was saying when he said that folks down in the cave will want to kill you if you try to pull them out of that context of looking at the shadows.

Dr. Cashio: The sad thing is that even if you take the climate change out of the equation, just looking at the economics of coal mining and the area they have dug up most of the coal. It’s cheaper to dig up the coal in other areas of the country, especially in the west. Coal mining companies are moving out west because that is where the coal is. When they do the coal mining here, they do a mountaintop removal or some version of that. Big environmental problem right there. It requires significantly less people to do that. Instead of having 50 miners mining the coal, you have five. These aren’t going to come back.

Dr. Weber: That peoples’ livelihoods are at issue here.

Dr. Cashio: Their livelihoods are at issue, and so they want someone to blame, which is a perfectly understandable human response.

Dr. Weber: But we have got to worry about truth.

Dr. Cashio: It’s when those perfectly understandable human responses get in the way, your basic human intuitions get in the way of actually what is going on, you end up hurting yourself more than you realize. You don’t want to stop watching the movie because it’s entertaining and it’s good.

Dr. Weber: Things used to be great and you want them to be great again. We’re talking with Dr. Anthony Cashio here on Philosophy Bakes Bread in just a few moments. Thank you so much for talking with us, Dr. Cashio, and keep listening, folks.

[Theme music]

Announcer: Who listens to the radio anymore? We do. WRFL Lexington.

Dr. Weber: Hey folks, this is Dr. Eric Thomas Weber here live in the studio. You’ve been listening, or if you have been listening, or if you just tuned in, you’ve been listening to Philosophy Bakes Bread: food for thought about life and leadership. It’s a production of the Society of Philosophers in America and it’s thinking about why and how philosophy matters in real life. I just wanted to take a short break for a second to remind you that you can reach out to us in a number of ways. We have had a few callers already, and I want you to be able to be recorded if that’s of interest to you. You can call and leave us a short, recorded message and we may be able to play it on a future show. That number is 859-257-1849. One more time: 859-257-1849. If you call and leave us a short, recorded message, as I say, we may be able to play it on one of the upcoming shows and have discussion about that question. I really appreciate any thoughts that you might have. We’re going to dive right back in.

Dr. Cashio: Hi there! Welcome back to Philosophy Bakes Bread. I’m Dr. Anthony Cashio and I’m here with Dr. Eric Weber.

Dr. Weber: Alright. We’re on a segment called “philosophunnies” of Philosophy Bakes Bread. We’ve got Dr. Anthony Cashio, a notoriously funny guy, and he’s going to tell us a philosophy joke. Share one with us.

Dr. Cashio: Is it solipsistic in here or is it just me?

(laughter)

Dr. Weber: What is solipsism? Let’s not explain a joke after the fact, let’s give some thought in advance first. What is solipsism?

Dr. Cashio: Solipsism is the view that the self, the individual, is all that can be known to exist. You know that you exist, but you don’t know that anything else or anyone else actually exists. It’s your own mind, everyone else could be an illusion or a zombie or projection.

Dr. Weber: Just like when you have someone lying to you, you think you know the truth of what they think and say, and that they love you or what have you, or that they are good citizens, but actually they could be some sort of spy or what have you. Everything can be false. Taking that kind of idea, that you don’t know the truth, to the n-th degree, you can not really know that anyone is actually real. This is all perhaps some fantasy or we are all in our own individual movies, like in The Truman Show. That’s sort of solipsism in a nutshell. Alright, now give us a solipsism joke.

Dr. Cashio: How did the solipsist break up with his girlfriend?

Dr. Weber: I don’t know. How did the solipsist break up with his girlfriend?

Dr. Cashio: “It’s not you, it’s me!”

(laughter)

Dr. Weber: Nicely done. Thank you Dr. Cashio.

Dr. Cashio: Philosophers explaining jokes! Ruining humor, one joke explained at a time.

Dr. Weber: No, I think the important thing is to explain a concept in advance and then tell the joke. You can’t explain the joke after.

Dr. Cashio: That was my thinking, actually. Should have explained solipsism and then hit them with a few jokes or something like that.

Dr. Weber: Thank you so much Dr. Cashio for giving us our first philosophunnies contribution here on Philosophy Bakes Bread.

Dr. Cashio: We need a rimshot.

(rimshot, laughter)

Dr. Weber: We actually recorded two jokes in this first interview that we did. Remember that this is the first episode airing like this. We may need to work out the bugs or kinks if there are any. I had a lot of fun talking with Anthony, and we have a second joke for you so I may as well go ahead and play it.

Dr. Cashio: Socrates is famous for the Socratic method where he goes around and asks people questions repeatedly in order to reach some level of truth. Plato was his most famous student. The joke goes something like this. What an awkward set up. When Plato first met Socrates, he says “Why don’t you have a girlfriend?” Socrates said “You ask too many questions”.

(laughter, rimshot)

Dr. Weber: You do have to be a bit of a philosopher nerd to find that funny. In some other episode maybe we will talk about Socrates’ wife Xanthippe. He’s not always as nice about Xanthippe as he should be.

Dr. Cashio: He was a really awful husband.

Dr. Weber: He was a pretty bad husband at some times. We’ll come back to that. We are going to have funnier and funnier philosophunnies I hope. If I’m wrong, the nice thing about telling a bad joke, is that at least people can laugh at you when you tell a bad joke. Either way. If you have got a philosophunny that you would like to send us, go ahead and reach out to us at philosophersinamerica@gmail.com. You can tweet us @PhilosophyBB, Philosophy Bakes Bread. You can also call and leave a voicemail and it will record for us and we can maybe play your, if it’s a short one, we could probably fit in and play one of your jokes on the show. Thanks so much to Dr. Cashio.

Dr. Weber: We have got two last segments here that are about to be aired. This is Dr. Eric Weber live in the studio. As I’ve said, I’ve got two main short segments to play for you. One is more serious, thinking about big-picture thoughts that Dr. Cashio has for us to conclude our session, interview and discussion about Plato’s cave and its importance today. Then I’ll ask him to give us a question to ask you guys for the segment that we’re going to have in the future called “You Tell Me!” I’ve given you a number of ways in which you can get in touch with us but I’ll come back to more details about that once you have heard the question. Here are those last two segments.

Dr. Weber: Hey everybody. We are back with Philosophy Bakes Bread: food for thought about life and leadership. This is Dr. Eric Thomas Weber talking with Dr. Anthony Cashio of UVA Wise, and we’ve been talking about the allegory of Plato’s cave and thinking through that lesson that Plato was telling us about how people are so used to seeing shadows on the wall and it’s hurting those when there is the real deal behind them, or at least, even better, outside of the cave that they are in. They don’t realize that they are looking at shadows. The enlightenment of turning around and seeing this blinding, blazing fire behind them that is projecting these shadows, that’s the source of it. But even better there is the outside of the cave there is light and trees and the real deal and everything.

Dr. Cashio has been explaining this allegory for us, and in the next segment we talked about how this is relevant in real life in the ways in which people for instance get themselves twisted around on issues like climate change and vaccination. We have fear for our kids and their health and so on. We can become irrational. We can also focus on our jobs to the point and wanting to focus on that ignoring and discounting any evidence about what’s happening in terms of the global climate because we have an interest in things like having more coal burn and so forth. Thank you so much Dr. Cashio, for talking with us. I want to invite you to give us any of your final thoughts about the contemporary relevance, if any, of Plato’s cave, and how we should think about the nature of truth, whether there are no facts or we should think about absolute truth, or maybe something in between? Tell us about that as well as the big-picture question I always want to ask, which is: Do you think that philosophy bakes bread? If so, how do you see that today with these examples and this allegory of Plato’s cave.

Dr. Cashio: I think that Plato’s allegory of the cave is so famous and so compelling because it is very easy to find, throughout history, people have been able to find how it relates to their lives. It’s so easy to get wrapped up in your family, wrapped up in your life, wrapped up in your job, wrapped up into politics, wrapped up in your religion, into the minutia, the things that gets under your skin, you get passionate about it, you get excited about it. They could mislead you. I think one of the really big lessons of the cave is a healthy skepticism. An attitude of when you get wrapped up and passionate, when you realize that you are arguing about shadows, take a moment and step back and think about what you are thinking about, which is philosophy. So it’s difficult. If philosophy is going to bake bread, to go with the analogy, we have to live in the cave. We have to go back into the cave. Philosophy doesn’t bake bread on the outside. There is a lot going on there, knowing the outside is part of it. But baking the bread takes place inside the cave, that’s where the fire is. So, it is difficult to do.

I think if you follow Plato’s allegory, you learn to have a healthy skepticism, to have a humility about your own ideas, to have a humility about the ideas of the people that you are talking to. It might seem irrational to want to not vaccinate your children, but it is not emotionally irrational to want to protect your children. A certain humility when talking to people who hold that position, because it’s not a completely out-there idea to want to protect your children. That’s a natural human instinct. Helping people to understand that maybe the best way to protect your child is to vaccinate. That’s a hard argument to make, but if you just dismiss their emotions and their experiences right off the bat, it works. You have to have a certain humility because you are in the cave. That’s how you begin to bake bread. This healthy skepticism is taking a step back with your own ideas as well. To be aware: “I feel that this is absolutely the way it ought to be.” Well when you have that word ‘I feel’ in there, that should send off warnings in your head, alarms: “Maybe I’m wrong”. I’m always happy to be wrong. I like it when people tell me I’m wrong. Then I go, “Oh, I was wrong.” And if they can show me why I was wrong, that’s even better. I go “OK. This is great. Now I’ve learned something. I’ve taken one more step out of the cave. One more slip down there, yeah I scraped my arm, but it’s worth the climb.” I think it’s always worth the climb out of the cave.

Dr. Weber: That’s a nice demonstration of why you are a philosopher. Most people, when they are shown that they are wrong, they feel upset, they feel attacked. What a philosopher can see when we learn about philosophy and we realize the importance of these attitudes, is that we can appreciate when someone shows us we’re wrong. We’re learning something.

Dr. Cashio: When I’m wrong I get upset at first. I’m like “No I’m not.” But eventually, you begin to appreciate that it is good to see that you’re wrong sometimes. You work your way out of the cave. What about you, Eric? What do you like about the cave? How do you think that fits?

Dr. Weber: Part of the problem is that today we criticize the media so pervasively as being always slanted. everything, every bit of information we talk about, people think of as charged and loaded. Therefore, there are no facts, there is no real world outside of the cave, people think, because all of the information that we get is filtered in that way. Yet it is so important for us to remember that the world pushes back and we can’t just have things any which way we want them. I may want, for instance, the injury my daughter suffered, I may want that to not have happened, or to be something easily remedied. But the world pushes back and we can’t just make things any which way we want. We may want jobs in coal country, and it’s a good thing to push for jobs and to care about those people and try to revitalize those economies, but we shouldn’t be stupid about how to pursue that further. There may be smarter ways of pursuing those reasonable ends.

Dr. Cashio: I love that phrase, ‘the world pushes back’. I think that might be the case. You might always know where we’re going, and yet the world always has a way of saying “Hold on, maybe you don’t know everything just yet.”

Dr. Weber: This is nice, and it gets back to what I think will be the word of the day for today, which is fallibilism, I was worried about this word. Fallibilism, what is that? That means that when you learn something, don’t think you’ve learned everything yet. Fallibilism means we can learn things and yet always have more that we need to learn about them. That’s the sense in which the world pushes back. I may think I know everything, but boom, all of a sudden, I encounter some problem with one of my beliefs and I realize that I’ve got to learn more. It seems to me that Plato’s cave pushes us always to remember that we can be focused on shadows, even if we have been outside the cave, we can get caught up in the movie again.

Dr. Cashio: It’s entertaining. It’s easy to get so caught up and everything. Remember that you have to take a step back.

Dr. Weber: We have to remember the ways in which we get affected and shaped. Even as philosophers, we in the academy are in a bubble, as folks have been saying lately. That’s true. We have a certain environment that allows us to do what we do and not everybody has that. Seeing past that, I think is really important. I can’t thank you enough, Dr. Cashio, for co-hosting Philosophy Bakes Bread here. I look forward to talking with you in the future about the ways in which philosophy matters to people in everyday life.

Dr. Cashio: I’m looking forward to it as well. I think it will be fun,

Dr. Weber: Awesome. So we’ve got one more segment I mentioned earlier, called “You Tell Me!”. I’m live here in the studio right now, this is Dr. Eric Weber on the show Philosophy Bakes Bread. I’m playing you recorded segments of an interview I did with Dr. Anthony Cashio of University of Virginia at Wise. He is going to be a future co-host of the show, but as a first episode I thought it would be fantastic to interview him in the first place. The next short segment is the question that we have for you all and we invite you to get in touch with us about your thoughts about that question. There will be information in this recorded segment about how to get in touch with us and then I’ll add to that at the very end.

Dr. Weber: Hey everybody. We’re going to have a new segment here that hopefully we are going to make a regular thing on the show. It’s called “You Tell Me!” and I or Dr. Cashio or another guest will ask you a question and we genuinely want to hear what you have to say about it. You can send us your thoughts about the following question on twitter @erictweber. You can also email us at philosophersinamerica@gmail.com. You can also get us on Facebook at Philosophers in America. Last but not least, you can also call and leave a voicemail and those voicemails will be recorded and if it’s OK with you we will play them on the show. That number is 859-257-1849. 859-257-1849. This is a segment called “You Tell Me!” We want to hear from you about the following question. Dr. Anthony Cashio, why don’t you tell us a question that we want to hear from our listeners about in our new segment “You Tell Me!”

Dr. Cashio: Well we have been discussing Plato’s allegory of the cave and about how one can have their opinions changed. The world pushes back and we get our opinions changed. I would love to hear from our listeners about an idea, a belief, something in their life that they have had an experience that has changed their ideas, their beliefs, their stance. They have made their way a little bit further out of the cave. For instance, I used to have very specific ideas about coal mining and its effect on the environment, but when I moved to Wise county, I got to meet and know a lot of coal miners and it really has changed my opinion and stance about coal mining and the way I approach the issue and the way I think about it. Something like that.

Dr. Weber: How did it change your views? What did it reveal?

Dr. Cashio: The concerns of the coal miners are genuine. They really do love their families and they want to protect their families so it is a deep, genuine, economic concern. Coal miners are not out to viciously destroy the environment. They want a livelihood and when they approach a mining site, they plan. There is a lot of planning that goes with it for how they are going to extract the coal and how they are going to restore the land afterwards. They love the land. They want to protect it. They also want to live off of it. Coal mining is a way to do that.

Dr. Weber: Dr. Cashio has just given us a wonderful example about having had his eyes opened, turned towards the light of truth from our positions in the cave. Why don’t you guys write us and tell us ways in which you had your eyes opened, some light shed on beliefs that you have held passionately, or perhaps without thinking about them. Reach out to us on Twitter, on Facebook, or on phone with the voicemail as I said. 859-257-1849. We would love to hear from you on Philosophy Bakes Bread: food for thought about life and leadership.

Dr. Weber: I mentioned that I was going to come back in and give you a little bit more information about how to get a hold of us because there are additional ways since we made this recording that we have created. Among them, you can get us at our Twitter profile that we now have for Philosophy Bakes Bread, it’s @PhilosophyBB. We’re also on Facebook, PhilosophyBakesBread, string that all in one word. Last but not least, if you are interested about learning more about the Society of Philosophers in America you can check us out online: Philosophersinamerica.com. Thanks for listening so much and tune in the same time next week for Philosophy Bakes Bread. We are airing Mondays at 2PM Eastern time. You can livestream the show, wrfl.fm/stream, and you can also subscribe to the show as a podcast. More information about that is going to come soon. The podcast comes out in the next day or two or so after the show airs, and that way you don’t have to miss a beat. Thanks again for listening.

[Outro Music]

[1] Today, that address is http://PhilosophyBakesBread.com.

How easily we ridicule those who disagree with us. Whether it’s Plato’s cave or Flatliners, we try to “illustrate” that we are right and those who disagree are just missing the point. If they were as clever as we were, they could see the truth as we see it. How rarely we take the position, required by intellectual humility, that what we see is actually the shadow.

Indeed! Now everyone other than me, stop that! 😉