(1 hr 15 mins)

Click here for a list of all the episodes of Philosophy Bakes Bread.

Subscribe to the podcast!

We’re on iTunes and Google Play, and we’ve got a regular RSS feed too!

Notes

- Dr. Tommy Curry’s new book, The Man-Not: Race, Class, Genre, and the Dilemmas of BlackManhood (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, forthcoming July 2017).

- The Society of Young Black Philosophers Facebook group.

You Tell Me!

For our future “You Tell Me!” segments, Dr. Tommy Curry proposed the following question in this episode, for which we invite your feedback: “Given the recent election of Trump, how do listeners reconcile the myth of American democratic progress with the regression in American race relations, where deportations, racial profiling, accusations of terrorism, and international bans now become synonymous with American freedom?” What do you think?

Let us know! Twitter, Facebook, Email, or by commenting here below!

Transcript Available

Transcribed by Drake Boling, June 5, 2017.

For those interested, here’s how to cite this transcript or episode for academic or professional purposes (for pagination, see the printable Adobe PDF version of this transcription):

Weber, Eric Thomas, Anthony Cashio, and Tommy Curry, “Studying Black Men,” Philosophy Bakes Bread, Transcribed by Drake Boling, WRFL Lexington 88.1 FM, Lexington, KY, March 6, 2017.

[Intro music]

Announcer: This podcast is brought to you by WRFL: Radio Free Lexington. Find us online at wrfl.fm. Catch us on your FM radio while you’re in central Kentucky at 88.1 FM, all the way to the left. Thank you for listening, and please be sure to subscribe.

Dr. Weber: You’re listening to WRFL Lexington 88.1 FM. This is Dr. Eric Thomas Weber and I’m here to play for you the ninth episode of Philosophy Bakes Bread. This is a great one with Dr. Tommy Curry and it’s going to be about black male studies.

[Theme music]

Dr. Weber: Hello and welcome to Philosophy Bakes Bread, food for thought about life and leadership, a production of the Society of Philosophers in America, A.K.A. SOPHIA. I’m Dr. Eric Thomas Weber.

Dr. Cashio: And I’m Dr. Anthony Cashio. A famous phrase says philosophy bakes no bread, that it’s not practical. But we at SOPHIA and on this show, aim to correct that misperception.

Dr. Weber: Philosophy Bakes Bread airs on WRFL Lexington 88.1 FM, and is recorded and distributed as a podcast next, so if you can’t catch us live on the air, subscribe and be sure to reach out to us. You can find us online at philosophybakesbread.com. We hope you’ll reach out to us on any of the topics we raise, or on topics you want us to bring up. Plus, we have a segment called “You tell me!” Listen for it, and let us know what you think.

Dr. Cashio: You can reach us in a number of ways! We are on twitter as @PhilosophyBB, which of course stands for Philosophy Bakes Bread. While you’re there, why don’t you check out SOPHIA’s Facebook page as well at Philosophers in America.

Dr. Weber: You can of course, also email us at philosophybakesbread@gmail.com, and you can call us and leave a short recorded message with a question, or a comment, or maybe bountiful praise that we may be able to play on the show at 859-257-1849. That number again is 859-257-1849.

Dr. Cashio: On today’s show we are very fortunate to be joined by Dr. Tommy Curry. How are you doing today Tommy?

Dr. Curry: I’m doing great. How are you Anthony?

Dr. Cashio: I’m doing great now that you’re here. We’re going to have a fun conversation today. Tommy is here to talk to us about his work in philosophy as well as his forthcoming book which will be coming out in July of this year. It’s called The Man-Not: Race, Class, Genre and the Dilemmas of Black Manhood.

Dr. Weber: Indeed. We’re so glad you’re here, thank you so much. Dr. Curry is professor of philosophy at Texas A&M University, where he researches and teaches about critical race theory in Afrikaans philosophy and anti-colonial economic thought and colonial sexuality studies, social and political philosophy and biomedical ethics. He is also executive director of Philosophy Born of Struggle, as well as the recipient of the U.S.C. Shoah Foundation’s 2016-2017 A.I. and Manet Scheppps Foundation teaching fellowship.

Dr. Cashio: Dr. Curry is a very busy man. Dr. Curry’s work spans the fields of philosophy, jurisprudence, and gender studies, in addition to Afrikaans studies. He is a prolific author, having published over 30 peer-reviewed articles and more than 15 book chapters. On top of his forthcoming book and another in development titled Another White Man’s Burden, he is also a recognized public philosopher, having appeared on Rob Redding’s radio show, Redding’s News Reviews for his segment “Talking Tough with Tommy.”

Dr. Weber: Tommy this first segment is called “Know Thyself!” and so we invite you to let us know whether you know thyself. Especially, tell us about yourself and your background and how you came to philosophy, and given that, what philosophy means to you.

Dr. Curry: I came to philosophy largely in high school. I’m a first-generation college student from Lake Charles, Louisiana, at the time was a very small town in the South that was mostly known for craw-fish. It’s a good thing to be known for. A little later it was known for steamboat casino gambling. They used to put them on the lake. During that period of time I was actually a high school debater. It was how I paid for college. I was 12, I started reading socialism. My parents used to get really worried, back then we didn’t have the internet in 1994 or 1995, to get stuff you had to go to the library and look up the numbers of different periodicals et cetera and try to buy them.

Dr. Cashio: So you were like “Mom and dad can you take me to them library so I can get a book on socialism? (laughter)

Dr. Curry: Yes. Here’s the crazy part. It was a debate argument so I didn’t want to run Marxism because tons of people had arguments about Marxism. I started calling socialist newspapers, The Worker, The Socialist Review, they sent me tons of stuff to my house, they were sending me all this communist socialist literature.

Dr. Cashio: You’re on a list somewhere.

Dr. Curry: I am. My parents became worried. I became more familiar with the idea of social industrial unionism, the idea of unions leading the avant-garde proletariat revolution in socialism. So I started reading that for a while, got interested in the economic theory. Then I went to debate camp and started researching critical legal studies and critical race theory. I was about 13 then that was my first debate camp. From that time I as in love with critical ideas and critical thought. I was debating, I thought, this is something I want to do. Because I was at college campuses doing this research, I saw professors, I saw college students, I was like, “Yeah, I think I could be very comfortable on college campuses.”

Dr. Cashio: You realized this at the age of 13?

Dr. Curry: I was about 14 or 15 when I decided that’s what I wanted.

Dr. Cashio: Still ahead of the curve.

Dr. Curry: It was a great experience. When you’re a debater at debate camp, you spend two weeks on a college campus. Things have changed so much, but back then you were always in the library and you had to make photocopies of what you wanted to use so you copied and make the cards. So actually back then you actually had to read everything. I was reading tons and tons of material and I fell in love with theory and critical thought. That brought me into philosophy, it was understanding how these critical arguments were being utilized to talk about things like social justice and racism and equality and economic inequality and exploitation. I didn’t come to it through a love of Plato, these were arguments I was reading in socialist propaganda. Other things like current affairs and international relations, that really became a big draw to me. I think that’s why I have such a vastly different understanding pf philosophy. For me philosophy isn’t the love of wisdom, or this academic enterprise. I think of philosophy as more of a method or a technique of synthesizing empirical data and seeing causal or explanatory theories. That’s why I think it is so necessary for philosophers to know the realities of every discipline, because I think our job is to be able to understand what are happening in terms of descriptive or empirical phenomena, and try to create causal theories that can account for all of those, it can tell people the mechanism that tells the relationship between the different phenomena. That’s a vastly different view than most philosophers have for what our task is.

Dr. Weber: That’s interesting, in prior episodes of this show we’ve noted the ways in which philosophy can be this corridor between different disciplines and why it is that a philosopher might be engaged in reading across different disciplines. I think we can see that in what you just said. It certainly sounds like a lot of work to do to make sure you understand all of the different disciplines.

Dr. Curry: Oh yeah, but I love reading. I genuinely love reading. I wake up everyday and I read either three chapters of a book or two articles. Sometimes it’s in genetics, sometimes it’s in epi-genetics, sometimes it’s in anthropology, sometimes it’s in economics, it just depends. Something, what do I not know, let’s find out about. I think that to be a really good philosopher, contrary to how our discipline works, we should be reading across fields and across disciplines. Even when we don’t understand the data analysis, I’m trying to teach myself [?], that’s my next major task. That keeps us well-informed about what’s going on and it gives us more fueled for us actually thinking about things conceptually that enriches our practical realities. That’s what stops us from being so removed from our real world context.

Dr. Curry: I wanted to ask about an earlier point, there’s a lot to talk about in regard to what you just said, but you also mentioned that your parents were really worried early on. What were they worried about?

Dr. Curry: I’m first-generation, they are high school, their 13, 14-year-old is getting all of this socialist literature mailed to the house. It came in boxes. Boxes and boxes of socialist newspaper. People were sending me all this stuff about how the communist revolution would solve racism and how the communist revolution is needed to solve the war in Iraq. This is not what you typically think that a teenager is into, much less a teenager in the south. Being from the south, you do understand there’s a stigma that southern people are less intelligent. It was just not a conversation that was happening in our school. I remember I wrote one of my papers, I think it was my junior paper for Mrs. Steven’s class on a critical race theory. She was like, “This is just…”, you know, I was talking about jurisprudence and economic bias and why racism comes before class in a junior paper. It was just a conversation that wasn’t being had at the time.

Dr. Weber: Sounds like a good paper.

Dr. Curry: I actually still have a copy of it. I look back at it now and it’s just like, I should have been a little more well-read before I jumped into that boat.

Dr. Cashio: You were a junior. Cut yourself some slack there.

Dr. Curry: It was a good idea. It was creative. That’s what those kinds of things did, it opened up a conversation.

Dr. Cashio: What did Mrs. Stevens, what did she think?

Dr. Curry: She said that she was impressed with my vocabulary.

Dr. Weber: That’s not always a compliment.

Dr. Curry: No it was. She was a great teacher. One of the reasons that I learned to write so precisely was because of Mrs. Stevens. When we are in high school, one of the first assignments, one of the first days of our English class, she made us write 300 sentences. 100 simple sentences, 100 compound sentences, and 100 compound-complex sentences. She gave us this kind of map about how you write papers. I think that literally, the trauma of writing 300 sentences in a night imprinted on me, and that’s why I write the way I write today. It was positive. She was a good teacher.

Dr. Weber: I want to follow up one more thing about something you said. You said something about how you differ from some people’s conceptions of philosophy as they think about the level of wisdom, as to where in your case you think of philosophy as a way of thinking about empirical evidence and synthesizing ideas for the sake of advocacy for progress. Is that right?

Dr. Curry: Yeah. I think that philosophy should do problem-solving. When you look at what other disciplines do, they are overwhelmingly concentrated on specific problems. If I read something in domestic violence, they are usually concerned with domestic violence on these groups of women, very rarely but sometimes these groups of men. At the same time if we look at the sexual abuse population, they are looking at the same population but only looking at sexual abuse. I think one of the things that the philosopher can do is instead of just pre-determining what you’re going to find with a theory, you have the ability to synthesize the findings in the sexual abuse literature and the findings in the domestic abuse literature to find commonality. One of the commonalities between those two literatures is previous sexual trauma and socio-economic status. Those things, while they are identified as specific causes or correlates in the respective literature, they don’t form a joint theory, there’s nothing that joins those two things together.

I think the philosopher has the ability to not only to reap that material, find that causal explanation, but also do that theoretical work, to work with theories that might explain that. If you take the sex role theory that you get from something like second-wave feminism, which would suggest that men abuse because they want to dominate women, the philosopher has the ability to track the thinking down behind that. You can go through the theories, you can go through the progressions, you can go through what the people are reading. Once you get past that, you can say “Here’s what is wrong with these assumptions. Here’s a better explanation, look how it explains reality much better. I think that’s what philosophers should be doing, we should be solving problems, be they ethical, be they social-political, bet hey clinical. I think we have contributions to make in clinical findings like domestic abuse, trauma, and previous sexual…I think all these things can matter if we jump out of our bubble which says that we literally hold up the bible of Dewey or the bible of Plato, or the bible of whoever we choose. I think it’s a limitation of our field. We have so much more exciting things to contribute if we just take up the task of educating ourselves about the world beyond the figure that we want to interpret the world through.

Dr. Weber: Very interesting. We’re going to come back to a number of the points you’ve just raised, Tommy. We’ll be talking after a short break with Dr. Curry first in a segment about race in the United States and in the modern world today, and then in the next segment about his book The Man-Not. We’ll be right back. Thanks so much for listening to Philosophy Bakes Bread.

Dr. Cashio: Welcome back to Philosophy Bakes Bread. This is Dr. Anthony Cashio and Dr. Eric Weber talking today with Dr. Tommy Curry. We were discussing black male studies, the topic of his forthcoming book with Temple University Press. This topic is unique Tommy, as it is not just about race, but about gender as well. It is about black males. As we discussed before on this show, we’ll start this segment to talk about issues of race and then we’ll focus on the next segment on gender, specifically on concerns special to black masculinity and black males.

Dr. Weber: Indeed. thank you so much for joining us, Tommy. As you know, this may be one of the obvious big picture questions. There has been talk in the past 8, 10 years, 8 years maybe, since Obama was elected, and a little bit before, that we might be in a so-called ‘post-racial’ time. So the question for you is: Are we past race, whatever that would mean? If not, how do you consider issues of race in a country that elected not once, but twice, an African American to our highest office?

Dr. Curry: When we look at race, we often have to distinguish between the symbolic gestures of progress and the material progress. This was a distinction that Derek Bell, before he died, was very insistent upon. He would suggest that when you have things like the Civil Rights movement, these are symbols of progress. Even when we learn things now, throughout disciplines, the civil Rights movement becomes the basis by which we read practically every race relation through. When we see this today even with Black Lives Matter, the reason that people protest in the streets is because it was modeled off of what they saw in the Civil Rights movement. That becomes the pinnacle focus of scholarship, of social protest, and even our conceptual lens of looking at racism in America. The problem with that, and this is what critical race theorists understood, people like Richard Delgado and Derek Bell understood was that means segregation becomes the conceptual lens by which we read something like the end of racism, or the decrease of racism. The more integrated something is, or the more access someone has to a position or office or job or social space, in our minds it’s coded as less racist. When you talk about something like Obama, it’s like, “Oh look, we de-segregated the last segregated bastion of white supremacy: the White House.”

What ends up happening with that, it’s like you put a black guy in the white house, and notice when Obama was elected, then there was a question of his race theme. White people suddenly wanted to claim his as a mixed-race president. There’s conversations like “He’s not black, he’s half-white.” When in the history of America has that ever happened? When have white people been like “That black guy is part of my race, he’s half white.” That shows you how race becomes this kind of malleable, but at the same time permanent feature of American consciousness. While you say we have got progress by putting a black guy in the white house, there is a problem with him being understood completely as a black man. There’s something about America’s racial consciousness that doesn’t allow it to fully accept that a black man could occupy that level of governance over a country. The other part about it too is that while people embrace the symbol, there is a simultaneous backlash against Obama. Many people argue that it’s this white-lash now, eight years later that got president Trump elected. You had the increase of the tea party. All of the moderates that saw themselves in Obama’s policies now shifted over to the right, became conservative. Even though he actually improved the economic and political status of more Americans, especially with him giving them affordable healthcare, these types of things suggest that racism operates at a level both cognitively, both how the perceive race and how they perceive black leadership in this country, but also materially.

How people see that they are disadvantaged next to other groups of people who they perceive as being black or other racialized minorities over them. You have a swell of poor white people who are middle class white people. You have the Occupy Wall Street movement who were literally being de-classed in a way. They saw themselves as middle class and were moving into a lower class. I talk about this in my work as a kind of ‘niggerization’ of white America. It doesn’t have the same class status that has traditionally been associated with whiteness, white privilege and white property. They saw the decrease of lower class literally racializing them as a group of people. This creates a problem in the collective consciousness in white America, which is why you have this huge sprawling of rural whites voting for someone like Trump. It means that race then becomes a central point of departure for how people relate to each other and how people conceptually understand the problem of governance. One of the things that I’m constantly talking about that I think philosophers get wrong about race is that they try to prioritize identity as it stands in for social stratification. What I mean by that is as philosophers often say something like, look at this last election for instance. The overwhelming number of white women who voted for Trump, who is by and large a misogynist and a xenophobic racist. You have this huge outpouring, but in most liberal philosophers’ minds, that was impossible because the position of gender means that you take the pro-gender stance. That you’re not as susceptible to misogyny and patriarchy as men would be because they are the dominant group in society. When you look at that empirically, white women been one of the most conservative voting blocks in the country, especially the past 50 or 60 years. Their attitudes mirror that of white men, just like in other racial groups. Their racial attitudes usually overwhelm gender difference or gender political attitudes within races.

When you look at something like Trump, a racial backlash, the analysis that you’re going to give are going to be racial stratification rather than gender divisions within the same groups. Philosophers often miss the mark. That’s why, you watch social media. You’ve seen the crisis of the discipline of philosophy. How could this happen in our America? Especially among American philosophers who largely see American democracy as not only a progressive social phenomenon, but a kind of ethos by which people try to understand and build communities. When that collapsed because there is a betrayal of the consciousness within communities, there is not really an apparatus to explain it because the way we decentralize race as an explanative phenomena or causality, in academic culture doesn’t allow us to really see that people largely align with racial interest over economic and even gender interest. It explains much more of phenomena at least socially in this country, than the other facets, which is not to say that they don’t have very serious or significant effects, but it doesn’t determine the course of history or politics the same way. That’s what happens when we look at race as in America.

We often talk about race as identity, race as skin color, race as something that we all have, versus racism, which are structures of power that are reproduced socially, economically, politically and conceptually. It leads into dehumanization or the eradication of certain racialized groups. When you look at things like that, you can actually see that Trump’s policies towards women are not gender policies, but in fact racial policies. If you think that Trump is trying to eat away women’s right to abortion because he hates women, then you have to say how traditionally white supremacist countries have looked in relationship to minorities. They have looked at them as the key, center facet of making sure that their population grows. It’s not surprising that someone is xenophobic and racist, who wants to block out immigrants and increase the white population, is against white women having abortions by and large. It fits within the general pattern that we see, especially at turn-of-the-century white idealism and white ethnological and ecological ideas. These things are reproductive ideas. This is the same way when Trump says that Mexicans are rapists, he’s not necessarily playing race politics, he’s playing gender politics.

One of the overarching ideas that people have had in the United States, especially perils, black or yellow peril, is that racialized men want to rape white women. If we change the dynamics by which we understand these concepts, then we can see very well why he resonated so much with some rural white women. They articulate their ideas of gender on racial concepts that have been historically rooted to their feared paranoia of being out-produced or overrun by racialized immigrants, racialized males typically.

Dr. Weber: I certainly remember all kinds of examples wherein white supremacists were deeply worried and pushing on the idea of our women and protecting them. I hadn’t made the connection, until you said that, to the way in which you would refer to Mexicans as rapists. Understanding how and why he got such support from the alt-right, which is this sugar-coating way of saying white supremacist. How he got such support from them, there are a number of ways. I hadn’t made that specific connection. That’s very interesting. I’m sorry, Anthony you were going to ask a question a little bit ago.

Dr. Cashio: Following this, is there any real potential for progress in the United States? Can we move beyond this or through this? How would that look going forward?

Dr. Curry: I think I’m more of the traditional, old-school race crit, so I would say no. Most afro-pessimists would agree with me in that conclusion. The reason, when scholars often say, especially black scholars and more specifically, black male scholars, say that there’s no progress on race in America, many people want to see that as a pessimist or fatalist position that is just not true. It’s not true because there’s some empirical verification that shows otherwise, it’s often not true because one cannot accept the idea. It’s absurd to accept that idea. But when you look, most people understand racism within the idea of change, but they understand change as only meaning improvement. What I’ve been really trying to tell philosophers, especially American philosophers, is that no one is arguing that there are not dynamics of racism, that it stays the same. But within the dynamics, within the fluidity of how race changes, like how Islam becomes a race, it becomes racialized. There is also a regression of race. There is the apex by which people get included in it and become more dangerous. To talk about racial progress without talking about the cyclical nature of regression, doesn’t allow us to articulate what happens in America when we’re trying to talk about race relations between other groups of people, or even how other races are racialized to demonize them. Now Islam, Muslims are now terrorists. These processes of change and dynamics and redefinition and cooptation and inclusion is what’s necessary to understand the kind of realism about the situation of race in America.

In terms of where you go from there, you literally have to change the whole structure. When you’re talking about racism you’re not talking about the thoughts of individual people. I think many people in the twenty-first century don’t understand. You’re not talking about how a person thinks about a group, that’s only implicated. You’re talking about how various structures and policies legitimize the attitudes of certain groups that then become socialized into a larger population, which is why individuals believe what they believe.

Dr. Weber: What is an example of that Tommy? I’m nodding and I appreciate the theoretical explanation you’re giving to us, but I can imagine a listener saying, “What is an example of that? What does that mean?”

Dr. Curry: An example of that would be what happened to Muslims in this country after 9/11. Islam was a religion. It is a religion. Now it becomes synonymous to terrorism because there is this event in the historical memory of America that relates the killing of Americans on American soil to Islam. What happens on the basis of that? We pass policies and declare war on Muslims. We are talking about the jihad, the terrorism, we’re talking about Isis, all of this is linked to our concept of Islam being always radical, always violent. From that stance the government takes after 9/11, different kind of policies of propaganda happen. That’s when the government starts accepting that this idea is in fact true. Once the public accepted that idea was true, notice how we now have a whole generation of people who are Americans, who grew up in an Obama era that not only called him a Muslim and anti-American, but now believes that Muslims is synonymous with anti-American terrorism.

The idea came about from a position that the leader at the time took about what happened at 9/11 and that trickled down to a reproductive concept that became cultural in the minds of individuals. Now you have American citizens two decades later that still fundamentally believe that this event was caused by this disposition of Islam. That’s what I mean. Most people would say that we need to target those individuals, without any analysis of how 9/11 plays into the collective memory, how certain policies and a declaration of war, and certain nations reproduced this phenomena, and the role that the state plays in making sure that this is still part of the national story, especially under someone like Trump, who is vehemently anti-Muslim and anti-immigrant.

Dr. Weber: It’s interesting that you say that, I was just having a conversation yesterday with someone who didn’t realize that the Klan thinks of itself as thoroughly Christian. There’s a reason they are burning crosses, it’s not because they hate crosses, it’s because they think they are Christian. Nobody will jump to say that Christianity as this kind of religion. It’s the clansmen are weird. It’s interesting how by contrast, you have certain people who call themselves Muslim doing some awful things. But not every Muslim.

Dr. Curry: I always think this is funny, because a lot of the research I do is on the Klan, especially in the early twentieth century. I tell people all the time. The Klan celebrated feminism, the Klan celebrated women’s suffrage. They thought it was literally the unification of the white race against the black race. That would have more votes to subjugate black people during Jim Crow.

Dr. Weber: Wow, I’ve never heard of that.

Dr. Curry: Yeah, they actually write this in their constitutions. There were all of these local chapters, so you can look at what they were saying about women getting the right to vote in 1919, 1920. They were overwhelmingly in support of it. White people were like welcomed by the Klan all over the country during Jim Crow. It’s so funny to me that, going off of your example of how we don’t associate Christianity, it’s funny how certain ideas and concepts get so de-historicized. The whole beginning of the Klan is based on Christian doctrine, based on this divine republic idea, which is why it was supported overwhelmingly by people who weren’t part of it as maintaining the white community. Doing God’s work. When those groups incorporated ideas that we think today as being completely liberal and completely anti-racist, we just separate the two, not because they are historically separated, like women’s suffrage and the KKK or white supremacy, but because we’ve made that decision in our time period to say that these things are not fundamentally related. We just de-couple them. Most things in America had to deal with racism. American democracy is about imperialism. Women’s rights, suffrage, was about imperialism.

All of these things were the links. The idea was not that women deserve equality, it was that women can join white men to rule. One of the pushbacks against black people getting the right to vote, or specifically black men getting the right to vote, was that white women felt that they were the superior group and felt that white men should enforce that. That’s why you had all this huge push of the myth of the black rapist, the tests, the lack of civilization of black people in America. You put that in context of what happens when Obama wins office, then it doesn’t become surprising that you have this huge pushback on the idea of being governed by a black man, who also became anti-American, who became a terrorist, who became barbaric et cetera.

Dr. Cashio: He was Muslim, therefore terrorist, and he is also black, so you have…three or four adjectives.

Dr. Weber: His middle name is Hussein!

Dr. Curry: Notice the idea was that he couldn’t be born here. Because the idea in the 19th century was that black people were aliens, because republics reflected the idea of the people who they were from. This has caused geography all the way back to the 18th century. These are very old ideas.

Dr. Weber: It’s a great sign that I want to keep talking, but we do have to take a break. We’re talking to the fantastic Dr. Tommy Curry and we’re going to come right back for another segment in just a moment. Thanks so much for listening to Philosophy Bakes Bread.

[Theme Music]

Announcer: Who listens to the radio anymore? We do. WRFL Lexington.

Dr. Cashio: You’re listening to Philosophy Bakes Bread. This is Dr. Anthony Cashio and Dr. Eric Weber and today we are very fortunate to be speaking with Dr. Tommy Curry about race and gender. In this segment we’re going to talk specifically about concerns that are especially important for understanding and thinking about circumstances about black men and boys, a topic that is not touched on much, if at all.

Dr. Weber: Indeed. Before we ask any particular questions, we want to read a couple paragraphs that are in the release about Dr. Curry’s book. “Tommy’s book The Man-Not is a justification for black male studies. He posits that we should conceptualize the black male as a victim oppressed by his sex. The ‘man-not’ therefore is a corrective of sorts, offering a concept of black males that could challenge existing accounts of black men and boys desiring the power of white men who oppress them that has been proliferated through academic research across disciplines.”

Dr. Cashio: “Tommy argues that black men struggled with death and suicide as well as abuse and rape, and their genred existence deserves study and theorization. This book offers intellectual, historical, sociological, and psychological evidence. Lots of evidence. The analysis of patriarchy offered by mainstream feminism, including black feminism, does not yet fully understand the role that homo-eroticism, sexual violence, and vulnerability play in the death and lives of black males. Tommy challenges how we think and perceive the conditions that actually affect all black males.” Sounds like a very ambitious book, Tommy. I have a question for you that is probably the first one that most people jump in their mind. What do you mean by ‘genred existence’?

Dr. Curry: Absolutely. Throughout history, gender was a concept that did not apply to black people, especially in the 19th century in the science of ethnology. Gender was a concept that only existed within patriarchal or civilized races. The only civilized race that possessed it was white people, or Europeans. Black people were called savages. They never developed in the minds of Europeans the necessary sex roles that would justify femininity or masculinity or what we would understand today as gender. Genre is a way, is a term introduced by Sylvia Winter, it’s something that has been described by Fanon and I would even argue Du Bois, talks about the ways in which colonialism and racism have distorted the idea of masculinity or femininity on the bodies of men and women. It’s a term that’s meant to capture the specific kind of oppression, that there’s certain bodies that we suffer under, rather than isolating those terms of oppression to what we think are causal theories of gender.

Dr. Weber: Genre, when we think about literature, genre as a topic or a way or style of doing things. Is that related in any way to the way that genre was used in the way you’re talking about it?

Dr. Curry: Winters doesn’t draw from that understanding. She thinks of genre more etymologically as referring to kind, or type of thing. She thinks that it’s necessary to talk about the kinds of oppressions these bodies or accumulations of bodies have had in colonial spaces, rather than gender, which creates a hierarchy of that. People like Oyèrónkẹ́ Oyěwùmí in The Invention of Women have argued that when you talk about gender, you already presuppose a kind of history in which women have been subjugated by men and that that holds true across all cultures. In fact, that doesn’t. The ways that most white women came in contact with racialized peoples were as colonizers. They were the people brought in, following Ann Stoler’s work, they came in after the genocide. After white men killed everybody, when they wanted to set up shop, build homes, institutions, churches, expand their population, that’s when the women came in. The idea that that gender history would be the same as the gender history of a native people’s, would be completely wrong.

Dr. Weber: One of the key premises of your book, Tommy, is that there is more that is important to talk about, than issues of race when you’re talking about black men and women. There are also crucial differences that are special or unique to black males. That’s part of what is going on in your book. Can you tell us, why do we need a book that focuses on black men in particular if the problem is racism? Someone might argue. Why is this needed, and this particular this focus that you’ve got in your book?

Dr. Curry: The existence of black men and boys in the United States is largely thought of as generic. That racism affects them in ways that often lead to their death, that’s often all we understand. One of the things that we see with he deaths of people like Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, Sean Bell, even a young boy like Tamir Rice, black men only become focused on when we’re analyzing their corpse when we’re trying to justify or analyze their deaths. We try to say that they are good people and didn’t deserve it only when we see their dead bodies in front of us. The at-large perception of black men and boys in this country is that they are dangerous, they are deviants, they are rapists, they are criminals. They are generally considered to be less intelligent than their female counterparts.

Dr. Cashio: Examples of toxic masculinity, I’ve heard it described recently.

Dr. Curry: Right, if you look at social media, black and brown men are often referred to as toxic masculines or hegemonic masculines, which means that they see power that they use violence and domination of women to construe masculinity. What I show in this book is that one, that’s a misreading of R.W.S. Connell’s theory. She does not include black or brown men or colonized men in the idea of hegemonic masculinity, because it’s a ruling class ideology. In fact, she understands the historical efforts that black men have made in the global south against colonization as a kind of radical resistance masculinity, rather than the hegemonic masculinity.

Dr. Weber: For your average listener, lots of people won’t know what you mean by hegemonic. I just want to see if we can put it in English.

Dr. Curry: Hegemonic masculinity is the idea that there is a dominant ideal masculinity which rules over a country or a republic. It’s patriarchy. It’s hegemonic not because it’s powerful, it’s hegemonic because it’s ideological.

It forms the basis and standard by which all other masculinities aspire to. It has an ideological and conscious-based control for gender and gendered norms are organized in a given society. One of the things that go along with this patriarchal epsilon is of course the emphasized femininity. The female counterpart that is supposed to protect at all costs, be that women in our country. These two ideas become the basis for the idea how R.W.S. Connell, at least initially, because she has changed her thinking, at least initially formulate the concept. But black men and brown men don’t have that kind of masculinity. They don’t come into the society as patriarchs who control economics or government. They are usually the victims of it. They are not people who outperform their female counterparts in society, in fact they are often criticized for not being able to protect or provide for the women because of their employment, because discrimination, because of incarceration, or because of the terrible problem of homicide.

What we’ve often done is used theories that were developed on Australian schoolboys in the 1980’s to articulate and describe what we take to be violent masculinity in black and brown men in the United States. Because those things have been completely different, one is talking about ruling class people, the other is talking about the impression that all people are the title phenomenon, all people suffer, they are poor or incarcerated, or they are victims of substance or drug abuse, somehow the terms become synonymous. What I think we need is more nuance when we’re talking about the suffering of black men and boys, that we can’t continue to look at them as perpetrators of violence when they suffer so overwhelmingly as victims of violence. We don’t really talk about men who are victims of domestic abuse in the United States. Most of the literature that is written on that comes from the UK, because the UK changed its views about domestic abuse in the mid-90’s. Because America is doesn’t understand that there is a symmetry of domestic abuse and inter-partner violence in the United States, men are largely ignored victims. Black men are disproportionately affected by domestic abuse at the hands of spouses and girlfriends, it is viewed to be impossible that these brutish, violent, deviant black men could actually be victims at the hands of a woman.

Dr. Cashio: In one version, the toxic masculinity, the idea that the average black male masculinity keeps them from seeing this other side as well.

Dr. Curry: Absolutely. In fact, we constantly misname it. Most people would suggest that domestic abuse in black men happens because men are trying to gain power over women. But overwhelmingly the research shows that domestic abuse in black communities are bi-directional, meaning that women hit men and men hit women, because of employment opportunities, because these are economic problems. Overwhelmingly, domestic abuse in this country happens among the poorest and the lowest socio-economic status groups in America. When you’re putting race into that, you’re finding additional issues of employment discrimination, substance abuse, recidivism, et cetera… This is what brings conflict. This is not a simple thing like all men abuse and all women are victims. Men can be victims and perpetrators and women can be victims or perpetrators. We don’t have a very good accounting theory for female perpetration and violence. It gets even more complicated when we talk about issues of rape.

Overwhelmingly, black men find themselves, especially when they are boys, having earlier sexual experiences than the general population. This means that they are at greater risk for things like statutory rape, forced or coerced rape by different groups, men and women. But because we don’t have a very good idea of female perpetrated rape in this country, we miss the kind of vulnerability and suffering that the young boys go through. Remember the UCR, the uniform criminal code, didn’t change in the United States about rape until January 1, 2013. Before that time, the definition of rape was the forced […] of a woman. Only in 2013 when the possibility to being made to penetrate, could men be seen as victims of rape. It because of the reclassification of the day that now shows that rape in this country between men and women, where men are victims and women are victims are practically equal. Most of our accounts in theory, because before men were raped previously to 2013 it was considered sexual assault. It was literally defined in a different category. If you reclassify it, the numbers are literally like 1.28 million versus 1.26 million. The numbers are very close in terms of victimization of men and women being raped in this country. We need to do a better job focusing on this vulnerability.

Dr. Weber: Tommy we’ve only got a little bit of time left in this segment so I want to make sure I ask one question. It’s clear to me that you’re right that men can be victims and it’s amazing that if a women is raped statutorily by a male teacher, but when a woman who is a teacher statutorily rapes young men, that is not taken as nearly so troubling to people.

Dr. Cashio: People are like “Oh yeah, I wish that had been me.” You hear that.

Dr. Weber: There will be that attitude. My question with the issue of victim. Who can deny that Michael Brown or Trayvon Martin were victims and that others are, and there was this judge who was selling young black men to private prisons in Pennsylvania and caught doing so, got 29 years. There’s no doubt that there’s victimhood. On the other hand, being called the victim and thinking of oneself as a victim is also stigmatized. There’s a negative influence of associating someone with victimhood. Can you talk about that at all? Is that something maybe inescapable? IF you are a victim, well then you are a victim.

Dr. Curry: The literature that is talking about victimhood often reverberates around a notion of identity politics, that these people are perpetually victims, and their victimhood is being claimed based off of what people view as material or actual oppression. What I’m claiming with black men is a little different in the sense that in a victim versus perpetrator binary, which is often how policy and law is directed, black men never end up being seen as victims or vulnerable or impacted by violence. They are always thought of as the cause of it. When you have situations where young boys who have had early sexual experiences of statutory rape growing up, let’s say that that young boy who was raped ends up beating his girlfriend or wife, abusing her. We point to that violence, because that snapshot of violence when he is 17 or 18 with his girlfriend feeds into the theory that men abuse women. But we miss the antecedent 10 years where this same young boy at the time is struggling with issues of being raped by a women. He had no mental health, no resources for mental health, no group to talk to, had to live with this kind of violence and trauma in silence and shame. In many ways he had to absorb it by re-orienting the events, so many times when young men are raped, they end up rationalizing this as something that they wanted or something that they controlled. That trauma then builds into how this person perceives women, but we don’t talk about the violence that he saw or was a victim of, we only talk about him as a perpetrator of a crime.

What this ends up doing is that it creates a space where on top of race, the hyper-sexualization of black men and boys ends up feeding into a predetermined analysis where rape, be it domestic abuse, be it inter-partner homicide, it all fits into a theory that these people want to dominate and abuse people rather than seeing that these are products of different traumas and histories where they were the victims first. Because we don’t treat that, we don’t have a kind of compassion to these groups of people. I try to tell people all the time, when you study black men and boys, you can’t come at it with the identity lens. You have to genuinely feel compassion for what these boys are suffering. When I write about black men and boys, and I think readers of the book will see this, I humanize them first. I don’t suppose that what black men did in slavery or during Jim Crow, is actually the nature of black men in the same way that you wouldn’t say that someone who is hungry or starving who goes out and kills someone for food would naturally be a murderer.

With black males, we don’t have that distinction. We see a group that is incarcerated, we see a group who in schools are often sectored off into special education classes, we see groups of young boys who overwhelmingly based off teacher’s expectations, be they white or black, are thought to be less intelligent than their female counterparts or their white counterparts. Then we assume that in this environment that their actions or behaviors that they display are based off of their nature, rather than a coping mechanism or the effects of their marginalization and oppression. What I’m trying to do is sensitize the world with actual facts about how many men and boys actually suffer from rape and suffer from domestic abuse and fear for their lives because of the high rates of homicide in their communities, or fear of incarceration. I think that’s a very different view that we get of black males in this society. Even in theory, which tries to make them human first, and then because they are humans, suggest that it’s not just their corpse that we should focus on, but the loss of their actual lives and living, which is why I’m constantly calling for a study of black male death and dying. I’m interested in the process of what it means to lose one’s life in the course of living.

Dr. Weber: We’ve been talking with Dr. Tommy Curry and we’ve got one more segment when we come back. It’s a good sign if we wish we had more time. Thank you so much for talking with us, and thanks everybody for listening to Philosophy Bakes Bread. We’ll be right back.

Dr. Weber: Hey folks, this is Dr. Eric Thomas Weber here live in the studio. You’re listening to WRFL 88.1 FM in Lexington here. We’ve got one more segment to play for you, I know it’s about 3 o’clock, but this is not to be missed. It’s concluding thoughts and such from episode 9 of Philosophy Bakes Bread with Dr. Anthony Cashio, my co-host, and me, talking with Dr. Tommy Curry of Texas A&M University.

Dr. Cashio: Welcome back everyone to Philosophy Bakes Bread. We’ve been talking today with Dr. Tommy Curry, and now we have some final big picture questions, some light-heater thoughts, and we’ll wrap everything up in this last section, maybe with a pressing philosophical question for our listeners to contact us about. We’ll have some information about that in a second. Eric, I think you had a question.

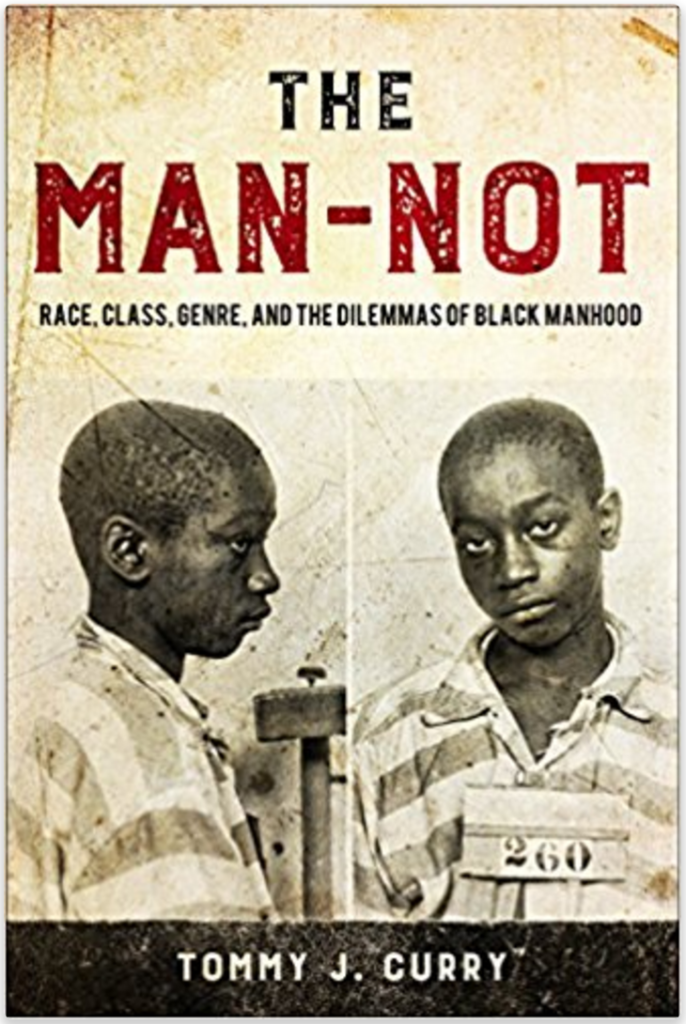

Dr. Weber: Thank you Anthony and thank you Tommy. Yes, I do have a question for you. Any of you, if you haven’t gone to take a look, you should. You can go check out, it’s available for pre-order on places like Amazon and elsewhere, The Man-Not by Dr. Tommy Curry. We’ll have a link in the show notes about that. On the cover of the book, which you can see on booksellers or the flyer about the book from the press, there are a powerful couple of photos about alternatively, you could say, a growing boy or a young man. My sense is that you picked this photo partly because he’s a young man, or he’s really a boy but maybe treated as a man, because he’s holding up whatever you call those letters when you are being arrested. Can you tell me the story about why you picked those set of photos for the cover, and what it means?

Dr. Curry: The photo is a picture of George Stinney Junior. He was a 14 year old black boy who was executed in this country for the crime of murder with intent to rape. He is the youngest person ever executed by the electric chair to this very day. The reason that I picked him was because there was not only evidence that he did not commit the crime, but there was an insistence, that despite the implausibility of it, that he was ultimately a rapist. The reason I chose that photo, was because it was necessary for me to center the fact that a black boy, a child, was considered a rapist because he was a black male. I look at that as one of the lens that black men in this country are often read through. It’s important to understand that whereas I see potentiality and innocence in him as a boy, that most people see him as a cub, as a not yet developed beast and rapist. Not only did he get seen that way, but he lost his life in a racist American south because of it, for allegedly attacking two white women. Fourteen years old. Imagine that, right? It carries a certain kind of weight. Tamir Rice was 12. This is the condition that most black males grow up with in this country.

Dr. Weber: This isn’t some sort of mob, though like in Mississippi. This is the courts.

Dr. Curry: The courts found him guilty and sentenced him to death. That’s the weight, the racism on a black male body. Fourteen. To think that we exist in a world where our dominant perspective of gender, which is formed by western feminism, doesn’t allow for that kind of vulnerability to be articulated. The idea is that it was racism, it wasn’t racism or sexism that killed George Stinney, but the idea of the rapist is in direct relation to the patriarch who aims to protect the women of his race. He was born in that moment. It was born in the moment of black male enfranchisement after the Civil War. It was completely about patriarchy. Rebecca Latimer is saying that she was against rape so we should lynch a thousand negros. She used to other N word, but that was about patriarchy. This is not just racism. But the kinds of violence and stereotypes and the terror and horror that black men have in the imaginations of most Americans, is often dismissed and silenced within the academy. In fact, to talk about black men as being vulnerable or to be victims of violence, be it police violence or rape, or even violence by women where women are perpetrators, is to literally be excluded by most sectors of the academy. It’s so taboo. IT’s something that we not only choose not to discuss, but something that we choose to disown because black males are so over-determined by the ideas of being violent that there’s no way that we can see that violent being as being the victim.

You have got to think about this. One of the ways there have been so much buy-in from police executions of black men in this country, has been on the idea that these black men were criminals and they had to protect their lives. Even the American public is like, “Well, if this black male would have done this or that, he would still be alive. Like Trayvon Martin, if he was respectful, he would have been alive.” This is a kid! You’re following a kid and pull a gun on him and shoot him in the heart, and the idea was that well if he was just more respectful, he wouldn’t have been seen as a legitimate threat.

Dr. Cashio: Then someone his being disrespectful justifies his murder, being killed.

Dr. Curry: These are the kinds of fantasies that we create. Somehow being disrespectful equals death. Walking down the street or pulling away from a cop equals death. A 12-year old boy like Tamir Rice, holding a gun, a BB gun, equals death. Anything that black men do that is outside of the realm of what society has confined them to, can most likely lead to death. That’s something that I don’t think we really understand in our analysis of black men. What we do is we count the numbers of bodies. Even the numbers of bodies are engaged. Even under intersectional theory, often the idea is that we focus on the death of black men far too much. Black men are killed on average, are 290, to over 300 black men are victims of police homicide. Their female counterparts are between 9 and 20 in a given year. The idea is that somehow theoretically we need to focus on black males’ deaths, because focusing on all men is patriarchal.

How do black men both become the greatest victims of patriarchal violence in terms of police homicide and state violence, but then to talk about them as the greatest victims, which is an empirical question, simultaneously becomes patriarchal violence or patriarchal silence. This is why the theories in the academy must be pushed beyond their present limits and boundaries. There is an erasure that depends on the dehumanized status of black and brown men and boys that allows for them to not be centered as primary victims. Could we imagine a world about where we said we talk too much about women being victims of domestic abuse? That would cause more outrage because there is a humanity to that. We talk about them, and male victims aren’t far behind female victims empirically, looking at both groups, but we still don’t center it. When we talk about men it seems like we’re deflecting from the larger issue. The humanity attributed to what female victims of domestic violence is so pronounced on these instances. But when you talk about black men as being primary victims of police homicide, or incarceration, because they are dehumanized and we see them as less than human, and undesirable, it’s much easier to claim why we don’t need to focus on them. Their humanity is not considered first and foremost.

Dr. Cashio: This is important and heavy stuff. We’re kind of running out of time, so we want to ask you a few last questions. One of our final questions we ask all of our guests is based on the inspiration of this show, whether or not philosophy bakes bread or does not bake bread, as the saying goes. As a philosopher and as doing philosophy, and we kind of talked about this at the beginning of the show, you have a different version of philosophy than a lot of other philosophers have. Do you find it helpful? That it helps bake bread? Do you find that you’re dealing with some very heavy stuff, do you find that it helps you keep sane? I guess is the right way to ask the question.

Dr. Curry: Let me say that I don’t think that most philosophy does bake bread. Because it’s completely impractical. I’ll be very specific with the traditions. I don’t think that analytic, continental or American actually contribute in its current form to the practical problems of our society. But I think that the ideas that we learn in philosophy really could. It could make us more sensitive and aware to problems if we get rid of reading or making philosophy synonymous to our dominant ideologies, be they pragmatism, feminism, or Marxism, whatever they may be. The task of the philosopher is conceptual specificity, the idea of using concepts to articulate causal relationships of specific problems. That’s why we enjoy Marx. That’s why we enjoy pragmatism. They make certain linkages between prongs of education and social stability and how they sought to make a more robust democratic nation.

The problem is that because we are less well-read than the people at the turn of the century, and we don’t value problems in the same way. They become ideological figures and idols for us rather than guidance or examples of how to proceed through a certain method of engaging a text’s concepts and problems. In terms of sanity, it’s not philosophy that keeps me sane. Most philosophy conferences simply don’t welcome this kind of work because it’s too challenging to our already comfortable ideas. The sanity comes from, and I have had to talk to several colleges, because we have IRB study with a colleague out of California.

One of the things that happen when you hear these stories, because black men would come to my office or they would call me up and meet me at conferences and they would tell me their stories of how they were abused and raped as young boys, you carry that with you. You carry the fact that in some instances, 20, 30-year old men have only been able to tell their story of rape because I read a paper that I acknowledged that black men can be victims of it. That’s a very powerful thing. To take on, and share in somebody’s suffering because you see them as a human and you see them as a human being where someone hurt them and disappointed them. The sanity comes from, and it took me a long time, because when I first started doing this work, I was really depressed. I was really impacted, it really affected me. Some days, I’m not a big crier, but hearing these stories and reading them, I would just tear up. It’s not just the violence that happened to them, but it’s the violence that we constantly do by denying that it happens. I would go on a conference and tell people here is what is happening to these young black boys, and people were like “It’s not a big problem.” or “Black men can’t be raped, men can’t be raped, they really want sex all the time.” I’m trying to explain to them, how is this any different than what they used to say about female victims of rape? “She wanted it, she dressed this way, she asked for it…” Why does this become so easily accessible as a desire that all men want.

Why do racialized men and boys, children, get lumped into that category. How does a 6-year-old boy want to have sex? That’s the hyper-sexualization of that group. What I’ve done, I have a group on Facebook where different black male scholars talk about their research, and I wrote a book, and it’s the first book ever that is dedicated to black men as the center of a study that is utilizing their own theories. That really helped me because it gave me a way to start understanding and explaining some of these issues that I was being told at conferences constantly, but couldn’t really get a hold of a person. When someone tells you that this terrible thing happened to them, that a mother’s friend, for instance, used to pay them, they were 9 years old, their mother’s friend would pay them to perform oral sex on her. When someone tells you that, and they tell you how it’s affected their relationship, that they would never be able to see themselves marrying a woman, and always felt like they were unattractive and underperform sexually because of this incident as a child, that they have linked money to this form of approval from females, what can you say as a philosopher? Philosophy doesn’t help you there. What helps you is understanding the humanity of the person speaking, and trying to say that there is something that you can do or develop that will get other people to sympathize with that pain.

The task of doing that as philosopher when you are studying black men and boys, is that you have to fight not for the argument, but for them to be heard. It’s not about winning the argument when this happens, it’s about getting people to hear the humanity of a voice crying out as a victim of a kind of violence as denied to them. I think that that orientation, realizing that fundamentally changed how I was approaching the study of black men and boys. That’s what actually gave me some sanity. It showed me that, before I was just doing the studies, I was like here’s the evidence, here’s the evidence. It was impacting me because it was like no matter how much evidence I presented, and I’ve presented at women and gender studies conferences. I’ve presented everywhere. I was trying to find an audience of people to hear this work, to understand that intersectionality in feminism hasn’t done it’s due diligence in talking about female perpetrated against males. Those people didn’t want to engage me. Perhaps I was naïve when first coming out. In trying to center and show that black men can be heard as human beings really gave me a purpose to taking on all of the suffering and trauma of these individuals.

Dr. Weber: Thank you so much Tommy. This is some very heavy stuff. Given how heavy this is, it’s really important to remind people about the lighter side of philosophy and have a little big of levity because every now and then you do have to smile and laugh even if things are rough. This next moment is a segment we call philosophunnies. I’ve recorded, actually my son saying the word “philosophunnies,” I’m going to insert it right here.

Dr. Weber: Say ‘philosophunnies’

Sam: Philosophunnies!

(laughter)

Dr. Weber: Say ‘philosophunnies’

Sam: Philosophunnies!

(child’s laughter)

Dr. Weber: I want to invite you, if you have any funny story or joke to tell us, do you have any funny story to tell us?

Dr. Curry: Not really.

Dr. Weber: The tragic part, when you’re looking for jokes in philosophy and race is that you see some of the gross stuff that’s out there on race. The most sobering one that was really kind of tragic and not-quite so horrible compared to other jokes, I have some good ones from Paul Mooney that we’re going to tell next. This first one is an indication about some of what we’ve just heard from Dr. Curry. Here is a joke that is not funny, but sad about MLK. What would Martin Luther King be if he was white? is the question. The answer is Alive. That’s pretty awful in a sense.

Dr. Curry: That’s awful, but ironically true.

Dr. Weber: That’s an example of the most palatable of some of the first jokes, when I say palatable, I mean like I don’t feel like a terrible person repeating it because of it’s truth and it gets at the point we’ve been making. That said, we have a couple of Paul Mooney jokes that I think are pretty funny. Anthony you want to try the first one there?

Dr. Cashio: This is Paul Mooney saying this, not me.

(laughter)

Dr. Weber: Not the white guy from Alabama?

Dr. Cashio: Paul Mooney says “I have nothing to do with racism in America. It was here when I got here.”

(laughter)

Dr. Curry: That’s definitely a Paul Mooney joke.

Dr. Weber: Yes it is. Paul Mooney says “White people are very good at acting like they are not racist. They deserve an academy award for that.” I’d like to thank the academy.

Dr. Cashio: One last one again is Paul Mooney, he says, “I love Obama because he is proof all black people don’t look alike. Nobody ever told me. Good morning, Mr. President. We don’t all look alike.

Dr. Weber: We need a rim shot.

(laughter, rimshot)

Dr. Cashio: Last but not least, we want to take advantage of the fact that today we have powerful social media that allow two-way communications even for programs like radio shows. We want to invite our listeners to send us their thoughts about big questions that we raise on the show.

Dr. Weber: Indeed. Given that, Tommy, we’d love to hear from you whether you have any big-picture question to ask our listeners for our segment that we call “You Tell Me!” Have you got a question that you would propose for them?

Dr Curry : Sure. I think given the recent election of Trump, I’d be interested to know how your listeners reconcile the myth of American democratic progress with the regression in American race relations where deportations, racial profiling, accusations of terrorism and international bans now become synonymous with American security and freedom.

Dr. Weber: There you have it. If you have got any answers for us, we’re about to tell you how you can send them to us.

Dr. Cashio: Thank you everyone, for listening to this episode of Philosophy Bakes Bread: food for thought about life and leadership. Your host Dr. Anthony Cashio and Dr. Eric Weber, we’ve been very privileged today, frankly, to be joined by Dr. Tommy Curry. We hope you listeners will enjoy us again. Consider sending your thought about anything that you’ve heard today, and we’ve heard a lot that you would like to hear about in the future, or the specific question that we have raised for you.

Dr. Weber: Indeed. Once again, you can reach us in a number of ways. We’re on twitter @PhilosophyBB, which stands for Philosophy Bakes Bread. We’re also on Facebook at Philosophy Bakes Bread, and check out SOPHIA’s Facebook page while you’re there, Philosophers in America.

You can of course, email us at philosophybakesbread@gmail.com, and you can also call us and leave a short, recorded message with a question or a comment that we may be able to play on the show in the future. We will play it. It’s fun and we like getting your calls. You can reach us at 859-257-1849. That’s 859-257-1849. Join us next time on Philosophy Bakes Bread: food for thought about life and leadership.

[Outro music]