Dr. Surprenant is the director of the Alexis de Tocqueville Project at the University of New Orleans. He is the author of Kant and the Cultivation of Virtue and the editor of Rethinking Punishment in the Era of Mass Incarceration (forthcoming), among many other works.

Listen for our “You Tell Me!” questions and for some jokes in one of our concluding segments, called “Philosophunnies.” Reach out to us on Facebook @PhilosophyBakesBread and on Twitter @PhilosophyBB; email us at philosophybakesbread@gmail.com; or call and record a voicemail that we play on the show, at 859.257.1849. Philosophy Bakes Bread is a production of the Society of Philosophers in America (SOPHIA). Check us out online at PhilosophyBakesBread.com and check out SOPHIA at PhilosophersInAmerica.com.

(1 hr 3 mins)

Click here for a list of all the episodes of Philosophy Bakes Bread.

Subscribe to the podcast!

We’re on iTunes and Google Play, and we’ve got a regular RSS feed too!

Notes

- The Alexis de Tocqueville Project at the University of New Orleans.

- Peter Wagner and Bernadette Rabuy, “Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie 2016,” [Press Release] The Prison Policy Initiative, March 14, 2016, https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2016.html.

You Tell Me!

For our future “You Tell Me!” segments, Dr. Surprenant proposed the following question in this episode, for which we invite your feedback: “What do we do with individuals who have committed crimes? If we don’t incarcerate them and if we think mass incarceration is a problem, what do we do instead?” What do you think?

Let us know! Twitter, Facebook, Email, or by commenting here below!

Transcript

Transcribed by Drake Boling, June 15, 2017.

For those interested, here’s how to cite this transcript or episode for academic or professional purposes (for pagination, see the printable, Adobe PDF version of this transcript):

Weber, Eric Thomas, Anthony Cashio, and Chris Surprenant, “Mass Incarceration,” Philosophy Bakes Bread, Transcribed by Drake Boling, WRFL Lexington 88.1 FM, Lexington, KY, March 20, 2017.

[Intro music]

Announcer: This podcast is brought to you by WRFL: Radio Free Lexington. Find us online at wrfl.fm. Catch us on your FM radio while you’re in central Kentucky at 88.1 FM, all the way to the left. Thank you for listening, and please be sure to subscribe.

Dr. Weber: Hey everybody. This is Dr. Eric Weber here live in the studio, and I’ve got for you a pre-recorded episode 11 of Philosophy Bakes Bread. This episode, we interview Dr. Chris Surprenant of The University of New Orleans on the subject of mass incarceration. Although these episodes so far have been pre-recorded, first of all you should know that some of them we intend to host live on the air in the near future. But in addition to that, just because they’re prerecorded doesn’t mean we aren’t thoroughly interested in and looking forward to your feedback, your comments, questions and so forth. We have a bunch of ways to get a hold of us and we’ll tell you about those in the show. We really do want to incorporate what you tell us, what you say to us in recorded voicemails and so forth. Without further ado, here is episode 11 of Philosophy Bakes Bread.

[Theme music]

Dr. Weber: Hello and welcome to Philosophy Bakes Bread: food for thought about life and leadership, a production of the Society of Philosophers in America, AKA SOPHIA. I’m Dr. Eric Thomas Weber.

Dr. Cashio: And I’m Dr. Cashio! A famous phrase says that philosophy bakes no bread, that it’s not practical. But we at SOPHIA and on this show aim to correct that misperception.

Dr. Weber: Philosophy Bakes Bread airs on WRFL Lexington 88.1 FM, and is recorded and distributed as a podcast next, so if you can’t catch us live on the air, subscribe and be sure to reach out to us. You can find us online at philosophybakesbread.com. We hope you’ll reach out to us on any of the topics we raise, or on topics you want us to bring up. Plus, we have a segment called “You Tell Me!” Listen for it, and let us know what you think.

Dr. Cashio: As always, you can reach us in a number of ways! We are on twitter as @PhilosophyBB, which, as always, stands for Philosophy Bakes Bread. While you’re there, check out SOPHIA’s Facebook page as well at Philosophers in America.

Dr. Weber: Indeed. You can also, also email us at philosophybakesbread@gmail.com, and you can call us and leave a short recorded message with a question, or a comment, or bountiful praise that we may be able to play on the show at 859-257-1849. That number is 859-257-1849.

Dr. Cashio: On today’s show we are very fortunate to be joined by Dr. Chris Surprenant. How are you doing, Chris?

Dr. Surprenant: I’m doing great, how are you doing?

Dr. Cashio: I’m doing great. It’s beautiful outside, we’re having a wonderful conversation. I’m excited. Chris is here to discuss criminal justice and especially problems of hyper-incarceration. Chris is an associate professor of philosophy at the University of New Orleans, where he is the founding director of the Alexis de Tocqueville Project, an academic center for research and programming focusing on issues at the intersection of ethics, individual freedom and law. Chris received his B.A. from Colby College and his PHD from Boston University. His areas of specialization are history of philosophy moral philosophy, and political philosophy.

Dr. Weber: Indeed. Chris is the author of Kant and the Cultivation of Virtue, from Routledge Press in 2014. He is also the co-editor of Kant and Education and Interpretations and Commentary with Routledge in 2011. His recent articles have appeared in Ethical Theory and Moral Practice, Educational Philosophy and Theory, Topoi, and edited volumes. Dr. Surprenant, as we heard, is the director of the Alexis de Tocqueville Project on Law, Liberty and Morality. I’m very glad to say that I had the opportunity to participating in an event there at the University of New Orleans and it was fantastic. He’s got a great community, he’s doing a lot of exciting work down there in New Orleans. The de Tocqueville project that he runs examines enduring questions in Western moral and political thought. The project sponsors public lectures, academic seminars, debates and reading groups, faculty and undergraduate scholarship, and summer seminar in philosophy and political economy, and for college credit, high school courses in philosophy. He’s doing a lot of good down south in New Orleans. In this first segment, Chris, we want to ask you some questions based on the crucial maxim “Know thyself!” We want to ask you, do you know yourself? If you do, tell us about yourself and how you got into philosophy, and what philosophy therefore means for you.

Dr. Surprenant: I think my story of how I got into philosophy is somewhat interesting. I suppose everyone thinks their story is interesting. When I was an undergraduate at Colby College, originally I thought that I was going into chemistry, the sciences. I was interested in the sciences in high school and applied to a number of big research universities. I ended going to Colby, and my first semester I was taking second-semester calculus, some sort of honors general chemistry class, some other science class, and I needed to find a course that could, or so I thought, could soften my schedule a bit. I was looking at classes and I saw this 2000-level environmental ethics course. I figured that this was going to be perfect, that I could argue with a bunch of tree-huggers for an hour or so two times a week, some papers and be done with it. The course was taught by Sarah Conly, who many of your listeners may know, she’s just an absolutely wonderful philosopher. She was a visiting professor at Colby when I was there, and she started off the class on the first day by going through the trolley problem. Her first example involved a dog and a human baby.

Dr. Weber: Let me interrupt you there and, for everybody, could you give a background for someone who has never heard of this, what big-picture is the trolley problem?

Dr. Surprenant: The trolley problem is way of trying to simplify moral decision-making. The thought is that you have two things on the tracks that have some moral value, but differing moral values. There is a trolley or a train that’s going to hit one of those things, and you have to decide, do you allow it to hit one thing? Do you switch the track and hit it somewhere else? How you go about making that decision and valuing those things is supposed to say something about your views in ethics and what we can value and why.

Dr. Weber: So like a trolley is barreling down the hill, and you can redirect it.

Dr. Surprenant: Exactly. So the question was: Do you have the trolley hit the dog or do you have the trolley hit the baby? Everyone of course said that you should switch the trolley and the track so it doesn’t hit the baby and it hits the dog instead. I put my hand up and I said, “Well, is it my dog?” and there was this pause, and Sarah Conly smiled, and I sort of went through an explanation of why I valued my dog more than some baby that I didn’t know and wasn’t aware of. She smirks all the way through it, and as soon as I’m done, she says, “I should talk with you after class. You need to think about becoming a philosophy major.” I sort of chopped the wood through he rest of the class. The interesting thing about that class was that it made me think a lot about questions of value that I hadn’t really thought about before, I started thinking that I should be thinking about if I wanted to live a rich and fulfilling life.

So I ended up taking more philosophy classes while I was there, never thought I would become a university professor. I ended up going to graduate school for philosophy and now I’m a tenured associate professor at the University of New Orleans. One of the things that is important for me now, is that I recognize that there are a lot of people who are never exposed to philosophy, never have an opportunity to think about these questions. One of the things that we’re going in New Orleans, and something that is very important to me, is to try to expose people to philosophical thinking, these questions, thinking about questions like What do they value in their life and why? Questions that most people are thinking about, but we live in a very fast world. Everyone, you wake up, you go to work, everyone is exhausted, they drive home, they go to sleep, and they just repeat it over and over again for years. That’s one of the challenges now, being able to take a step back and thinking about some of these issues that do take a little bit of leisure time. We try to provide opportunities for people in the New Orleans area, not just out students, but we do that too, to have an opportunity to think about some of these questions, to understand what philosophy is and why philosophy has value.

Dr. Weber: Chris, you mentioned this trolley problem as something that was important in your story in coming to be interested in studying philosophy further. Your answer was, “Wait a minute, is this my dog that might get hit by the trolley, or is this just any dog?” Explain for our listeners why whose dog it is matters. How do you think about that morally?

Dr. Surprenant: It mattered to me. One of the questions you need to answer when you’re looking at things that have moral worth, is how do you decide between them? Most of your listeners would say this is an obvious choice that you value the life of the human being over the life of the dog. The next question that I would ask is “Why?” Why is that the case? Is it because we have a type of familiarity with the person, that we understand what it’s like to be a person, what type of thing that is, and we understand there is a depth of thought there, or things that that being can accomplish that the dog can’t. But I don’t think it is unreasonable for someone to say “This thing is closer to me, and this is why I’m going to value it more. Let me change that example just a bit. One of the questions that I’ll run, the same trolley problem with my students on the first day of Ethics, and usually everyone says that they would hit the dog. Then I’d say talk about why. Imagine that you had one person on the tracks, and then five. Now you can usually get people to say “What if I know that person? What if that person was my mother?” Do we think it is unreasonable for a person to say, send the trolley at the five people instead of having it hit their mother? No. Just because it’s unreasonable doesn’t mean it’s the correct thing to do. I think you can come up with an explanation as to why that is the morally right thing to do. Issues of proximity and how important things are to individual persons matter in moral decision-making. We value things differently. That’s not a bad thing. Ethics is not about trying to arrive at one universal set of values, but understanding why we value the things that we value, and to what degree and whether or not valuing them in that way is reasonable.

Dr. Weber: Right on. I’m glad you explained that because one theory in ethics wants us to not think about whose pain or pleasure we are worried about when we make decisions about ethics insofar as we shouldn’t prioritize ourselves and be selfish, might be the theory of someone who holds to utilitarianism. This notion of having a special relationship, who can deny, very few people can say they don’t have a special relationship with their mother, their sibling or so on. What does it mean to have a special relationship? In your case it’s interesting is that it’s a special relationship to a dog, and of course lots of people would say they have that. It’s just fascinating, the issues that you bring up. I’m interested in how you think about the nature of philosophy, given your background. Speak to people who haven’t had a chance to go to college, maybe don’t want to, but are interested in the deep questions because many people are. What is philosophy?

Dr. Surprenant: The question ‘What is philosophy?’ is really interesting because the way we think about education now in this country, philosophy has become a discipline. It’s a discipline that you study in school like history or math or physics or whatever else. I don’t think that’s right. I think philosophy is a way of approaching the world. It’s a way of thinking through certain questions and addressing certain problems. It’s a methodology. It’s not that philosophy would teach you why you should value the dog over the child. That’s not right. Rather, philosophy will teach you, or allow you to address how we think through what we value. Sure, it’s the case that most people, and I imagine the vast majority, probably myself, if I really think through it, are going to do things like value the child over the dog in the trolley problem. The question is Why? What is the theoretical reason beyond “it’s just obvious”? That’s not helpful in questions or issues that are difficult. One of the things that I tell my intro class on the first day in introduction to philosophy, because most of them will never take another philosophy class, even people who are not interested in philosophy or never taken a class in philosophy or haven’t been to college, when you think about a PHD, there are PHD’s in all disciplines. That’s a doctor of philosophy, a theoretical doctorate.

There are theoretical issues underlying most of the questions that we’re thinking about on a daily basis. Not so much questions like “What am I going to pick up from the grocery store for dinner?”, but really important questions that affect our lives. For example, I have a small child. My wife and I are thinking through what type of school we want to send our child to. The decision that we make for our child’s future in this way, is going to affect her in a fairly significant way. There are lot of theoretical questions surrounding that. At least, when you have options. When you are someone who doesn’t have schooling options, there’s not much of a theoretical discussion to be had there. There are lots of cases where you have to make important decisions about your life, the trajectory of your life, and there are theoretical underpinnings to those decisions. Even for someone who hasn’t gone to college, hasn’t taken any classes in philosophy, the methodology, the approaches that we use in the discipline, the analytical approach to it, and sort of a reason-based decision making is important and should be employed. I think people become better off when they think through certain problems in this way.

Dr. Weber: Thanks so much, Chris. I really appreciate how you think about philosophy as well as recognizing not only that it’s something important in the academy, but also everyday life as well as every discipline, in a way, there are important, theoretical concerns going on. It may not be that the grocery list we write is philosophically interesting to people, there may not be philosophical issues that people are thinking about when they are trying to figure out what’s for dinner, although there are interesting philosophies of food out there that are starting up. The notion of “How should we raise our children?” is a great example of an everyday issue that is a philosophical question that so many people do or need to ponder. That’s a really nice example for thinking about ways in which philosophy can bake bread. Think about anybody that has kids, may need to confront certain philosophical questions about what it is they are trying to do, exactly.

Dr. Cashio: Asking the questions, “What kind of parent am I going to be? What kind of adult do I want my child to grow into? What values do I want them to express?” is a great way of thinking about how you value life and how you think about life and how you should go about approaching you projects.

Dr. Weber: Exactly right. That’s a great point for us to leave off on just before we take a short break with Philosophy Bakes Bread. We’ll be right back with Dr. Chris Surprenant and my co-host Dr. Anthony Cashio. This is Dr. Eric Weber. Thanks so much everybody for listening. We’ll be right back.

Dr. Cashio: Welcome back everyone to Philosophy Bakes Bread. This is Dr. Anthony Cashio, and I’m here today with Dr. Eric Weber, my co-host, and we are talking with Dr. Chris Surprenant about criminal justice in this segment. I know Chris does a lot of work in this area. Next segment we’ll talk more about mass or hyper-incarceration. So Chris, why don’t you tell us about how you got interested in criminal justice. We talked last sections about philosophy and how it gives value to life. How do you go from thinking about these big philosophical questions to thinking about them in terms of issues regarding criminal justice?

Dr. Surprenant: When I came to the University of New Orleans five years ago, one of the things that I wanted to do, since we are the public university for the city of New Orleans, is to think about how some of these issues that I look at, the theoretical issues in philosophy, and the things that I have been studying or working on for the past ten or so years, are relevant to the people in our community. One of the things that is directly relevant to a large number of folks in our community is criminal justice, whether that is just minor annoyances like how our city government seems to like to use the police as revenue collecting agents. There is a lot of ticketing during Mardi-gras and festivals and people get up in arms over that, or more serious issues like our incarceration problem, which I know we will talk about in a bit. Issues related to criminal justice are very relevant to folks in New Orleans more so than a lot of other places in the country because of issues related to say disproportion, or [statistics?], and people of certain colors getting pulled over. These are issues that affect people here and these are issues that we can get people interested in. There are also issues that you can approach from a variety of different perspectives. You can approach them from a philosophical perspective, or you can approach them from the standpoint of say politics or political science or economics, or sociology or psychology, or even history. This is our way of trying to bring an interdisciplinary approach to a very practical problem or a practical question that affects New Orleans, it affects the entire United States but I think affects New Orleans in a way that is disproportionate than other places.

Dr. Weber: That’s interesting and it’s great to hear not only that you’re thinking about the importance of philosophy beyond the academy, but I really appreciate your attention to the local community, because there’s a lot of people who think of publicly engaged philosophy as just submitting a piece to the New York Times or something like that. It’s wonderful to have pieces come out there, but there are communities that need engagement with philosophical ideas and I appreciate what you’re doing there in New Orleans. I want to ask you, Chris, in particular about one area of conflict in the sphere of criminal justice that has to do with marijuana. As you know, a number of states have legalized in various ways consumption and distribution of marijuana whether for medicinal purposes or just for recreational. Therefore we are having conflict between states’ policies and the federal government because the federal government hasn’t decriminalized marijuana. Because we have differences between states and some states experimenting with some things, president Obama had chosen not to prosecute in those states with respect to marijuana. We recently heard that the Trump administration has taken a different stance on that and will be prosecuting. My question for you is the philosophical question in terms of criminal justice: How do we determine what should be decided at the state level versus the federal level in cases like this or other ones?

Dr. Surprenant: I’m not going to pump that question, but I’m going to say that there are at least two philosophical issues here. One is theoretically, how do we go about making those decisions, or how should we go about making those decisions. The second question, which I think is probably less interesting are the facts of law questions, where the question is “What is the procedure for going about making those decisions in the United States, given how the Constitution is set up, given the federal government and the state government. Let me go to the first question. At what point should the federal government step in and say, overrule decisions of states. The only answer to that question is either when you are looking at a significant security issue or a significant rights issue. If you have states that pass various laws that infringe or violate the rights of American citizens, then the federal government can and should step in to rectify those things. In the same way, if you have a state government that is doing something that is reckless or otherwise may harm citizens in their own state or citizens in another state, or put US citizens in danger, the federal government should step in there as well.

Let me give you an example. Say what you will about the TSA, but it’s probably the case that we should have some degree of airport security, whether that just means metal detectors and luggage screening, or something else. Imagine if we had 50 different standards for airport security. Each state would have…it’s more of a nightmare than it is right now. It’s already kind of a nightmare, but we could imagine if we had 50 different standards. This isn’t just a coordination issue, because there are coordination questions. It’s useful to make sure that, say, a drivers’ license issued to me is valid in Virginia. That’s fine. Thinking like a safety issue, if you have different safety rules or different screening procedures, or even to the licensing thing, that if the state of Louisiana allows people to drive but the state of Virginia would not allow people to drive, because the state of Louisiana is reckless and is trying to raise more money by selling more licenses…(laughter). I say that because it’s a hypothetical, but in many of these cases it’s not! In those cases you’re looking at the federal government being able to step in and justifiably stepping in. Take marijuana. That was your example. It’s not clear to me how someone using marijuana is dangerous in any way or certainly more dangerous than all of the various substances that we allow people to consume. As best as I can tell, it’s less dangerous than cigarettes. As best as I can tell, all of the concerns about marijuana being a gateway drug to stronger drugs or harder drugs or more dangerous drugs, all of that seems to be false. It wouldn’t surprise me if the cigarette industry and various lobbyists were behind a lot of this stuff behind to prevent the legalization of marijuana. That hasn’t come out, but if you’re interested in conspiracy theories, I would put a decent bit of money on that.

Dr. Cashio: I’ve seen pharmaceutical companies. I’ve seen that conspiracy theory.

Dr. Surprenant: Pharmaceutical companies, but you can imagine regulating it. I don’t mean regulating it in a way that they regulate the decongestant Sudafed. You could just regulate in as in taxing it and selling it. I don’t quite understand, and I know we’re going to talk about mass incarceration here soon, there’s a link there between drug legalization and incarceration. But it doesn’t seem to me that there are really any good reasons for criminalizing marijuana, the use of it, or the possession of it.

Dr. Weber: When we are thinking about the state versus federal level kind of stuff, you’re saying a compelling reason why the federal government should supersede the states’ decision, you don’t see a compelling reason why the federal government should do that.

Dr. Surprenant: Correct. I don’t see it causing any harm to people to be on what might be caused by any of the various things that are already legalized, and I don’t see any rights issue. Legalizing marijuana does not protect the rights of individuals whose rights are otherwise being violated. There’s no security issue, there’s no national coordination issue, and there’s no rights issue.

Dr. Cashio: The argument that is usually given for criminalization is security, as you pointed out, that it leads to gateway drug use. Jeff Sessions said this just a few weeks ago, about how it leads to the opioid epidemic. It’s just not true.

Dr. Weber: If the person you buy marijuana from has to be selling it illegally, that person is more likely to have other illegal substances. I can see that argument, but if you are only selling something, let’s say, at the pharmacy, they are not selling you stronger drugs, crystal meth and such.

Dr. Surprenant: There’s no question that there is a lot of violence associated with the drug trade right now. Think about this. Imagine if in the US, the current administration woke up one morning and decided that it was going to ban all sales of chocolate. Like Kit-Kats.

Dr. Weber: Good luck with that!

Dr. Surprenant: I know. Think about the violence that would be associated with acquiring and distributing chocolate. You could tell stories about how chocolate corrupts people, and how it causes people to get cavities, or whatever else. They would be silly. They would be silly. If you’re looking down the road, I think you’re going to see a full legalization of this very soon. I think you’ve got folks holding onto, I’m not going to say that they’re being manipulated by certain lobbyists, I think many of them actually believe that the product is dangerous. I haven’t seen anything for that, and I think even if it is dangerous, to a certain degree, you have to let people make their own decisions about their lives. There are a lot of things that I do that are dangerous. I live in New Orleans. There is a lot of food that I eat that has taken months, if not years off my life. People choose to smoke cigarettes; they do other crazy things like… beignets, these are the powdered donuts that we have,

Dr. Weber: Deep fried flour covered with sugar. Those are good.

Dr. Surprenant: By the way, for listeners, they are not donuts. I’ve been living in New Orleans my whole life, I recognize that they are not donuts, but if you haven’t had a beignets, you don’t know what it is, it’s kind of like a donut. There are a lot of things that we do. My wife really enjoys going down icy hills seemingly out of control on skis. That’s incredibly dangerous. I do not like participating in that activity. But we don’t ban it. We have to understand why we are implementing certain laws, what’s the motivation for doing it. I think a lot of the stuff that we do in this country, it’s always done under the banner of public safety. Whenever someone wants to pass something through or limit peoples’ freedoms or do something, it’s done under public safety. The vast majority of the time, there are no legitimate public safety reasons for doing what people want to do.

Let me give you one more example relevant to New Orleans, and probably other places in the country. There is a proliferation of traffic cameras in New Orleans. These are both speed cameras and red light cameras. When the mayor just decided to extend the contract with this out-of-state company to put up more red light cameras, he went and cited public safety reasons. For the most part, there are no public safety studies that have shown that red light cameras do anything but cause more problems. People now slam on their brakes to avoid going through, which causes more back-end collisions. It’s pretty much a wash. There are some studies that have shown that the cameras do reduce certain types of accidents, the type of accidents that are more likely to cause fatalities, but all in all it’s negligible. Why do municipalities do this? Because they are trying to raise revenue. You have to look at what the motivations are for these sort of things. That’s my concern whenever you do something at the federal level or the state level when you are looking at issues of criminal justice, when you are looking at issues of restricting individual liberty, what are the actual motivations? What are the reasons why these folks are interested in passing these laws? Is it really a public safety thing or is there something else going on?

Dr. Weber: This is a really good point and a good moment for us to stop and transition because you have uncovered the incredibly important fact in issues of money in criminal justice. We’re going to come back and talk about hyper incarceration or mass incarceration and incarceration is big business. We look forward to talking with you further in the next segment, Chris, after a short break, on Philosophy Bakes Bread with my co-host Dr. Anthony Cashio. We’re talking with Dr. Chris Surprenant. Thanks so much for listening, everybody, on Philosophy Bakes Bread. We’ll be right back.

Dr. Cashio: Welcome back, everybody. You’re listening to Philosophy Bakes Bread. This is Dr. Anthony Cashio with Dr. Eric Weber and today we’re talking with Dr. Chris Surprenant. We have been discussing criminal justice and in this section we’re going to discuss mass incarceration or hyper-incarceration. Chris has a book coming out later this year, an edited collection of essay called Rethinking Punishment in the Era of Mass Incarceration. It will be coming out with Routledge Press later this year. He is well-placed to have good discussion about this. Alright Chris, a question for you. In many states, prisons are run under the name of “Department of Corrections”. Would you say that the United States genuinely makes an effort to correct peoples’ character and behavior in such departments? Do you think that’s a misnomer? Should we call it maybe the Department of Punishment?

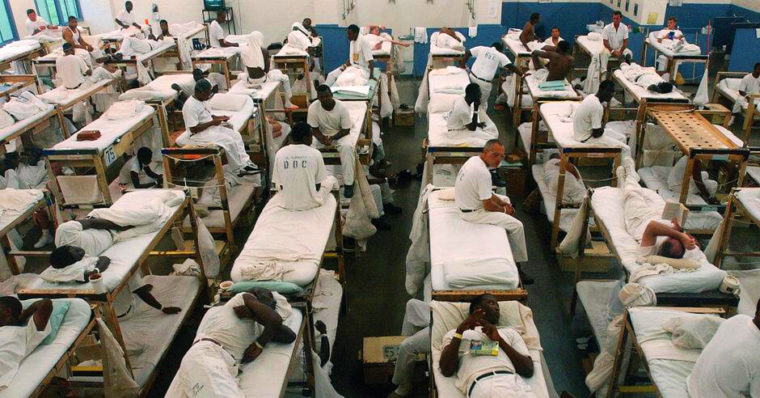

Dr. Surprenant: The “Department of Revenue Collection”. It’s the department of revenue collection for the people that can’t afford attorneys. In all seriousness, we put a lot of people in prison. Your listeners need to know the statistics. Right now, we’ve got 2.3 million people currently in the prisons in the United States, both at the county level, state level and federal level. That’s .71 percent of out population, or 1 out of every 140 Americans that are in prison. If you add parole and probation, you have got 820,000 people or so on parole, and another 3.8 million people on probation. Three-point-eight million. One out of every 46 Americans, or 7 million people who are under the control of the United States criminal justice system in one way or another. That is a staggering number of people.

Dr. Weber: But this is the land of the free, right?

Dr. Surprenant: It’s a staggering number of people. Here is the concern. Couple that with my general belief that for the most part, and again we hear stories all the time that break this general rule, but for the most part, the people going to prison are guilty and that our courts are doing a reasonably good job of identifying people that have actually committed the crimes they are accused of. The vast majority of cases end up plea-bargaining out. People going to prison often are being punished for lesser crimes or lesser things than they actually did. This is really the challenge, because it’s not so much that of these 7 million people that are under the control of the US criminal justice system, that 3 million haven’t done what they have been accused of doing. That’s just not true. I don’t think in the vast majority of cases cops are bad people, that prosecutors are bad people, that judges are bad people, even that the politicians are bad people. I’ll joke about being motivated by money and being motivated by lobbyists or whatever else, but the vast majority of these people just want to do their job, they want to feed their families, they want to go home, they want to live large just like all of us.

Many of your listeners are probably involved in the criminal justice system. The first thing that we have to do is recognize that there probably is not systemic racism or other abuses on the level that would get you these staggering numbers. There is no doubt that those things exist. No doubt that there are problems of racism in our criminal justice system. You see disproportionate sentencing all of the time. We just talked about marijuana laws, if I was walking down the street with a joint, I wouldn’t get arrested, I wouldn’t get anything done to me. If I was a black guy in New Orleans, I might have other problems. Those are issues to address. But that doesn’t get you to the number that we have now.

Dr. Cashio: So how did we get there then?

Dr. Surprenant: That’s a good question. One of the problems is that we think that what we need is some national policy, or that the problem is there on the national level, and that’s simply not true. The vast majority of people in our criminal justice system are affected at the county level or the parish level in Louisiana, or at the state level. What you have is a bunch of individual counties or parishes running their own jails because it’s profitable to do so. The state is doing the same thing as well. There’s no one-size-fits-all fix to this. You have to start looking at what’s going on in each individual state, each individual parish. It’s one of the things why this topic is important in New Orleans. If you are familiar with incarceration statistics, Louisiana leads the nation as of last year, per capita incarceration. Orleans Parish, as of a couple of years ago, leads Louisiana in per capita incarceration. The United States leads the world, with the exception of the Seychelles Islands in per capita incarceration. Using a little bit of fuzzy logic, if the U.S. leads the world, and Louisiana leads the U.S. and Orleans Parish leads Louisiana, then Orleans Parish ends up being the per capita incarceration capital of the world. It’s fuzzy logic because there are other counties that are higher, but that’s not a good place to be at. It’s not good that Louisiana always comes up last when looking at education statistics but it comes up first in incarceration statistics. There are problems. We have to figure out how to address these problems. That’s one of the things we’re trying to do here in New Orleans, looking at different solutions.

One of the solutions alluded to earlier, immediately decriminalizing marijuana, probably decriminalizing all drug possession across the board, treating drug possession as a medical issue is going to address most of these problems. If someone has a serious drug problem, they should not be in a prison. They should be in some sort of a care facility. Someone who possesses a small amount of marijuana shouldn’t even be there. That’s just a regular guy looking to go about his business. There’s no reason any of those people should be in prison. One question that you might ask is “Why are they in prison?” There is a financial incentive to get them there. State budgets, county budgets are stretched, and one of the ways of getting money from the federal government or getting money from people is putting people in prison. Once you align the incentives in this way, it’s no real surprise that people end up in prison. You mentioned that Jeff Sessions had talked about ramping back up the private prisons. If people are concerned about private prisons because they are for profit, but let’s be very clear. All incarceration in this country is for profit, for the most part. You can draw a distinctions perhaps between private prisons and public prisons, but all of these prisons are for profit. Unless we are talking about the small number of people who pose a physical danger to other people in society, the motivating factor in incarcerating the vast majority of our fellow citizens is for financial gain.

Dr. Weber: When you say ‘for profit’, it’s not that the institution housing them is necessarily something which ends up having a profit at the end of the year, distributing to shareholders, but rather that there’s huge amounts of money whether for profit or state, there’s a lot of people employed there, depending on that money. We’re talking big bucks. I seem to remember, the lowest numbers I’ve heard $17,000 an inmate, the highest number I read was $60,000 a year per inmate. Maybe more like 40,000 as an average. I’m not entirely sure about my numbers on that. But we’re talking big bucks, whatever of those is correct or closer to right. We’re talking big bucks every year. I remember also this terrible case of a judge in Pennsylvania who got 29 years for effectively selling young black men to prisons. He was paid, he got millions of dollars for that. He was certainly profiting even though he was in a public position.

Dr. Surprenant: There are a lot of stories where you have obvious issues of racism, obvious things that are illegal. Why I like to move people off of those stories very quickly is because those are the exceptions. I’m not interested in dealing with the exceptions. Those can be dealt with on a case-by-case basis. The problem is the rule, what happens all of the time that puts people in prison. The vast majority of judges are not doing anything crooked. The vast majority of them have their hands tied when it comes to sentencing. What’s the alternative? We saw a case not too long ago out in California, it’s the case of the former Stanford swimmer who was intoxicated and raped a girl behind the fraternity house, the girl was passed out. He got, what did he get—six months probation, three months in prison, something like that. There was an outrage. Part of the outrage was because of the way the judge presented it or the way the judge framed it and said “Look, we don’t want to ruin this kid’s life.” That’s probably not the right thing to say. But what if the judge came out and said this: “Look, I have evaluated all of the information,” and I’m not defending this guy, this guy seems like a sleaze-ball. “I’ve evaluated all of the information, and this seemed to be a case where you had someone who was very very drunk and you had someone who was basically passed out or on the verge of being passed out. When you look at this kid’s other behavior, he does not seem like he is the type of person who would be raping people on the streets. So I do not think, me the judge, if I’m the judge, “I do not think that the appropriate sentence for this person is to stick this person in prison where the public has to pay for him. Instead we’re going to put him out on probation, we’re going to have some sort of monitoring, we’re going to go through other procedures.” If he approaches the issue like that, you want to say, at least I would think that people would want to say that is a reasonable way to address some of these concerns. Other people may say this is not reasonable at all, that this guy should be in prison for ten years. That’s one of the challenges in this country. I don’t think a lot of people are all that concerned in part because I don’t think that a lot of people think that they will ever be the targets of the criminal justice system. The vast majority of our politicians seem to be making laws that they believe never will apply to them and never will apply to their important constituents.

Dr. Weber: In one of our recent episodes, we were talking with Dr. Tommy Curry, and he’s got a book coming out called The Man-Not. On the cover there are two photographs of what looks to be a young boy, and he is in front of the plates that have information like you’ve been arrested. It is a young boy. Turn out, it’s a 14 year-old named George Stinney, who was put to death for a rape-homicide, and it was thought that there was plenty of evidence to suggest that it wasn’t him, but because they said he’s a rapist and so forth. I appreciate your point that we have systematic over-incarceration above and beyond the special cases. This case of a guy who is an athlete and in college and white, “Oh this guy’s not going to go around raping people.” Oof. You know. Thinking about places like New Orleans and where I lived, in Mississippi, there are lots of people who get vastly greater punishments and that is a serious problem. That doesn’t mean necessarily that the world is going to be better if we have more incarceration. We have so much incarceration, but it makes one’s hairs go up to hear about a 14 year old boy put to death, especially when the evidence wasn’t so good.

Dr. Surprenant: Of course it doesn’t. Again, I think those are, we can start pointing out different examples, but we’ve got a question of, this is not the Stanford case obviously, but how do we deal with nonviolent offenders, generally? But also there is a question of violent offenders. We want to say “Let’s deal with the nonviolent offenders in a different way from the violent offenders.” But in some cases the violent offenders may not pose a threat to anyone in society. If someone has been in prison for 10 years and they are in their mid-40’s or mid-50’s, and all of the sociological data suggests that if you let this person out they are not going to commit any more crimes, or they’re not going to commit violent crimes, should that person really be in prison? These are the questions that we need to start asking. Right now we all seem to recognize that there is a problem, but it is not clear at all what the solution is. Even if you can come up with a solution in the classroom, a lot of these solutions are not viable politically, or not viable practically, given the abuse of people in the country right now.

Dr. Weber: Thank you so much, Chris. We’re out of time for this segment. We’re going to take a short break and come back with one more segment with Dr. Chris Surprenant. We’re talking about problems in the criminal justice system and hyper-incarceration and so forth. Thanks so much for talking with us on Philosophy Bakes Bread with my colleague Dr. Anthony Cashio and myself Dr. Eric Weber and talking with Dr. Chris Surprenant. Everybody we’ll be right back.

Dr. Cashio: Welcome back everyone. This is Dr. Anthony Cashio and I’m here today with Dr. Eric Weber, my co-host on Philosophy Bakes Bread. We have been, this afternoon, talking with Dr. Chris Surprenant, and we’ve been talking about criminal justice and mass incarceration. We’re going to wrap up with a few last questions, some light-hearted thoughts, and a pressing philosophical question for you, our listeners, as well as how to get a hold of us with some comments, questions, praise, complaints, et cetera. Chris, I have a question for you. Based on some of the stuff we’ve talked about in the last section. Accepting, and I think you’re probably right, that while there are some systemic issues involving corruption and systemic issues involving racism with the system of incarceration that we have, we still have mass numbers of people incarcerated. There’s just no way, hopefully, there’s no way that these systemic problems are big enough to account for this many people being incarcerated. What if, instead of mass incarceration being a problem, it’s a sign of success? If these people, the judges, the policemen and the criminal justice system is working well and we have real criminals going to jail, isn’t that what we’re supposed to have?

Dr. Surprenant: Punishment, yeah. If we’re identifying people who are actually doing something wrong and then punishing them appropriately, proportionately, then that would be successful. I think that there are a lot of cases where people are going to jail, because the drug laws are a good example, where they are not doing anything wrong, and I think that there are a lot of other cases where the punishments are not proportional. There are a lot of issues where we have a case right around the same time as the Stanford case, where you had someone who had stolen $12 worth of Snickers bars from a convenience store, and they were trying to put him in jail for something like 20 years to life, because as a habitual offender, he was a petty theft habitual offender. You can see why people put laws in the books like that, that people get tired of theft. I don’t think that the reason why they put a law like that in the books is say, racist. You look at this and you scratch your head and you say that this isn’t justice, this isn’t proportional punishment. I think that’s what we need to aim at. We should aim at proportional punishment. We should aim at justice, and not so much necessarily putting people away.

Dr. Weber: Interesting. Do you have any final takeaways you want to leave our listeners with, Chris, about criminal justice in the big picture, or about mass incarceration? Any final thoughts you have for everybody?

Dr. Surprenant: My final thought is that this is a very difficult issue. It’s a difficult issue theoretically, but it’s also a difficult issue practically and politically. What we need to do is to have a reasonably honest discussion in this country about what the aims of our criminal justice system are, and what we should be doing. The only way that you have this discussion is to do so without accusing the other side of being racist, or bigots, or whatever else. Bring everyone to the table, figure out what we’re trying to do, and go from there. In many ways this is a political problem. This is a problem that we can solve. There are a lot of problems that aren’t our own doing. It’s not that our own doing is that people are doing wrong things, but rather how we respond to that. We could, immediately tomorrow, end our mass incarceration problem by just letting everyone out of prison. That would probably not be a good idea. But it seems like a significant percentage of people in prison, if they were released, or maybe they shouldn’t have been there in the first place. If they were released, they may not do much of any harm to anyone in our society. We need to start thinking about what these solutions are. What are we going to do? How are we going to change the laws? How are we going to change the various punishment rules and procedures to try to avoid what many people on both sides recognize as a significant problem for our country.

Dr. Weber: Thanks so much, Chris. In every one of these episodes, we want people to think a little bit about the nature of philosophy and whether and how it metaphorically bakes bread. We’re interested in hearing from you whether or not you would say that philosophy bakes bread, and if you would, what do you say to people who don’t think so, who say philosophy doesn’t bake bread? That this is silly stuff. How do you respond to such people when they have that attitude? Or is that what you think and why should we think in that way? What do you say about the question about whether philosophy bakes bread?

Dr. Surprenant: Unfortunately, I think a lot of the stuff that professional philosophers do is silly stuff, or can be regarded by the vast majority of people as silly stuff. I think one of the things you’re looking at when you understand what the function of a university is is that you want to have a lot of really smart people doing work in relatively narrowly focused ways, because other people can come along and make use of that work and show how it is relevant for other projects. You see this in the sciences all the time. You see grants to study just absolutely bizarre stuff like microbes in a lake, or certain types of algae, or whatever. You go “Why are we giving millions of dollars to this?” At some point down the road, those things, maybe not all of them, but many of those things can be incredibly useful. It’s very useful to have future leaders of our country thinking about these questions. I don’t know where else you would do that in a structured environment that is conducive to this type of discussion than having it in a classroom. That’s one of the most dangerous things, and we don’t want to get too far in the field here, but one of the most dangerous things about some of these free speech issues on campuses right now, shouting down speakers and whatever else.

We need free discourse on our colleges and university campuses to promote this type of discussion. It’s incredibly valuable to our society, it’s incredibly for future citizens. This is how intelligent political participation happens. You only need to look so far back as the last election to see that what we need is more critical thinking, more intelligent engagement, more civility, more understanding how to talk with people on the other side. That’s one of the things that happens in philosophy. I’m not sure if that bakes bread in the sense of being a lucrative career, but it certainly bakes bread in the sense of getting a functional democracy and a functional public discourse on issues of great importance.

Dr. Cashio: Very good. As you know, Chris, we want people to know that while there’s a serious side to philosophy, there’s also a lighter side as well. We have a last little segment on our show called ‘philosophunnies’.

Dr. Surprenant: That’s terrible, just so you know.

Dr. Weber: Thank you. We’ve got a little recording of my son saying the words and we’ll insert it right here, because it’s pretty funny to hear him say it.

Dr. Weber: Say ‘philosophunnies’

Sam: Philosophunnies!

(laughter)

Dr. Weber: Say ‘philosophunnies’

Sam: Philosophunnies!

(child’s laughter)

Dr. Cashio: We’d love to hear if you have any favorite jokes, or a funny story or something that’s happened, anything philosophy related, especially if it has to do with issues of criminal justice.

Dr. Weber: Or just about philosophy generally.

Dr. Surprenant: I was going to say, because there are so many jokes to tell about criminal justice reform. Let me tell you a story from one of my first years at UNL. I went into this, I was teaching this intro class, and we were talking about moral controversies and a number of students were defending moral relativism, this view that there are no things that are objectively right or wrong, and I asked the students, “Can you give me an example of things that you would find to be morally blameworthy? The worst thing that you can think of.” There was a male African-American student in who hadn’t said anything in class. He put his hand up and I was going to call on him. He came to class very well dressed every day. Not suit and tie, but red or green or orange track suit, matching shoes, matching hat at the sideways angle. He put himself together every day. Not my style, but he clearly thought a great deal about what he was wearing and this was important to him. He puts his hand up and I said “OK, what do you think is worse than anything else you can think of?” and he says “When someone tries to steal my swag.” Everyone in the class starts laughing. I said, OK wait a second. Now we have a student who volunteered something, and this is meaningful to him. I said, “OK, what do you mean?” and he goes “You know, when someone tries to steal my image, who I am as a person.” I go “OK, now we’re talking. Let me get this straight. If I walked into class on Thursday, and I came to class and had the orange track suit on,” and everyone’s laughing at this point. He’s sort of smiling, “and I had the orange shoes on, I had my orange hat, like a Puma hat, like Rickie Fowler, the golfer has, at the angle, and I walked in, would you think I’m morally blameworthy? I’m trying to steal your swag?” and he looks at me, he’s got this smile on his face, and he says, “Nah, man. You can’t steal my swag.” The whole class starts laughing like, “Yeah, this 35 year old white guy can’t steal my swag.” But I know he was worried about it, and you know what he’s talking about. It’s a really great example of how you can interject humor and light-heartedness to make an important point.

What was great too was that after that day he also interested and participated more in class, and a lot of these students have very valuable contributions, but the way they see some of these philosophical issues and the way they want to contribute is very different than other students that we may be more used to in a philosophy class or the students that would go to graduate school. That’s been one of the biggest adjustments moving from say, Boston University to Tulane University, now to the University of New Orleans, is that we have students with very different backgrounds, and they approach these problems in a very different way. It’s been a learning experience just as much for me to try to understand how they approach these problems than just thinking through them in the way that say, I thought through them as an undergraduate.

Dr. Weber: That’s a great story, and in fact I want to highlight how central that is in so many ways, to thinking about philosophy, this notion of someone stealing his swag. When you think about it, we start for a reason with “Know Thyself”, like who you are matters, and someone is trying to steal who you are. That’s interesting.

Dr. Cashio: Should we switch it to “Give us your swag”.

Dr. Weber: “What’s your swag like?” We’ve grabbed a few jokes as well, just to make sure that we have some for today’s show about either jail or incarceration stuff. You want to give us one, Anthony?

Dr. Cashio: Eric, why did the picture go to jail?

Dr. Weber: I don’t know. Why did the picture go to jail?

Cashio: Because it was framed.

Dr. Surprenant: Good Lord, that’s awful.

Dr. Weber: It appears that a hole has appeared in the lady’s changing room at the downtown sports club. Police are looking into it. That was bad.

Dr. Cashio: Did you hear about the guys that got stealing a calendar?

Dr. Weber: No, what happened?

Dr. Cashio: They each got six months.

Dr. Weber: Energizer Bunny arrested: charged with battery.

(laughter, rimshot)

Dr. Cashio: Last but not least, we want to take advantage of the fact that today we have powerful social media, hopefully we are using it ethically, that allow two-way communications even for programs like radio shows. We want to invite our listeners to send us their thoughts about big questions that we raise on the show. I think we have raised quite a few this episode.

Dr. Weber: Given that, Chris, we’d love to hear what you think in terms of what is a question that you propose we ask our listeners for our “You Tell Me!” segment. Have you got a question that you would propose we ask everybody who is listening?

Dr. Surprenant: A serious question?

Dr. Weber: Yeah, well you can have a funny question too.

Dr. Surprenant: A serious question would be to think about what do we do with some of these individuals who have committed crimes? If the solution is not to incarcerate them, what do we do? What is the appropriate approach? I think that it’s easy to come in and say that we’re incarcerating too many people, what our approach to doing what we are doing is unjust. We have to do something different. When people ask me, I start talking about what they do in Singapore with caning, but most people think that’s barbaric. My question would be: What do we do if we think mass incarceration is a problem, what is a practical solution to this problem?

Dr. Weber: There you have it. There is the question everybody. Thanks so much for your question, Chris.

Dr. Cashio: Thanks for listening to this episode of Philosophy Bakes Bread: food for thought about life and leadership. We your hosts, me, Dr. Anthony Cashio and Dr. Eric Weber, are so grateful today to have been joined today by Dr. Chris Surprenant. We hope you listeners will join us again. Consider sending your thought about anything that you’ve heard today that you would like to hear about in the future, or about the specific questions that we have raised for you. What do we do if we are not going to incarcerate?

Dr. Weber: Once again, you can reach us in a number of ways. We’re on twitter @PhilosophyBB, which stands for Philosophy Bakes Bread. We’re also on Facebook at Philosophy Bakes Bread, and check out our SOPHIA’s Facebook page while you’re there, Philosophers in America.

Dr. Cashio: You can of course, email us at philosophybakesbread@gmail.com, and you can also call us and leave a short, recorded message with a question or a comment that we may be able to play on the show at 859-257-1849. That’s 859-257-1849. Join us next time on Philosophy Bakes Bread: food for thought about life and leadership.

[Outro music]