Dr. Lake is assistant professor in the department of Liberal Studies at Grand Valley State University, with her Ph.D. in Philosophy. In 2016, she was honored with the John Lachs Award for Public Philosophy from the Society for the Advancement of American Philosophy. She is the author of Institutions and Process: Problems of Today, Misguided Answers from Yesterday (2008), in addition to many journal articles.

Listen for our “You Tell Me!” questions and for some jokes in one of our concluding segments, called “Philosophunnies.” Reach out to us on Facebook @PhilosophyBakesBread and on Twitter @PhilosophyBB; email us at philosophybakesbread@gmail.com; or call and record a voicemail that we play on the show, at 859.257.1849. Philosophy Bakes Bread is a production of the Society of Philosophers in America (SOPHIA). Check us out online at PhilosophyBakesBread.com and check out SOPHIA at PhilosophersInAmerica.com.

(1 hr 9 mins)

Click here for a list of all the episodes of Philosophy Bakes Bread.

Subscribe to the podcast!

We’re on iTunes and Google Play, and we’ve got a regular RSS feed too!

Notes

- Jostein Gaarder, Sophie’s World (2007).

- Jean Paul Sartre, “Existentialism Is a Humanism,” Online for free, or on Amazon.

- Epictetus, Handbook (aka Enchiridion), Online for free, or on Amazon.

- The Internet Classics Archive.

You Tell Me!

For our future “You Tell Me!” segments, Dr. Lake proposed the following question in this episode, for which we invite your feedback: “How can you today step across the divides that we have and engage and advocate for progress with regard to the shared problems that we face?” What do you think?

Let us know! Twitter, Facebook, Email, or by commenting here below!

Transcript

For those interested, here’s how to cite this transcript or episode for academic or professional purposes (for pagination, refer to the printable, Adobe PDF version of this transcript):

Weber, Eric Thomas, Anthony Cashio, and Danielle Lake, “That’s a Wicked Problem You’ve Got There,” Philosophy Bakes Bread,

Transcribed by Drake Boling, WRFL Lexington 88.1 FM, Lexington, KY, March 27, 2017.

[Intro music]

Announcer: This podcast is brought to you by WRFL: Radio Free Lexington. Find us online at wrfl.fm. Catch us on your FM radio while you’re in central Kentucky at 88.1 FM, all the way to the left. Thank you for listening, and please be sure to subscribe.

[Theme music]

Dr. Weber: Hello and welcome to Philosophy Bakes Bread: food for thought about life and leadership, a production of the Society of Philosophers in America, AKA AOPHIA. I’m Dr. Eric Thomas Weber.

Dr. Cashio: And I’m Dr. Anthony Cashio. A famous phrase says that philosophy bakes no bread, that it’s not practical. We here at SOPHIA and on this show aim to correct that misperception.

Dr. Weber: Philosophy Bakes Bread airs on WRFL Lexington 88.1 FM, and is recorded and distributed as a podcast next, so if you can’t catch us live on the air, subscribe and be sure to reach out to us. You can find us online at philosophybakesbread.com. We hope you’ll reach out to us on any of the topics we raise, or on topics you want us to bring up. Plus, we have a segment called “You Tell Me!” Listen for it, and let us know what you think.

Dr. Cashio: Tell us. You can reach us in a number of ways. We are on twitter as @PhilosophyBB, which, if you can’t figure it out, stands for Philosophy Bakes Bread. We’re also on Facebook at Philosophy Bakes Bread, and check out SOPHIA’s Facebook page while you’re there. Great little page at Philosophers in America.

Dr. Weber: In addition, you can email us at philosophybakesbread@gmail.com, or can call us and leave a short recorded message with a question, or a comment, or bountiful praise that we may be able to play on the show at 859-257-1849. 859-257-1849. On today’s episode, we didn’t get a chance to pre-record a “You Tell Me!” segment, and so I’m going to tell you a little bit about the feedback we’ve gotten in the past week or two, and I’ll do that live here in the studio and after that I’ll return you to the remainder of the pre-recorded episode of Philosophy Bakes Bread, episode 12 with Dr. Danielle Lake on wicked problems.

Before we get to that, I want to let everybody know that last week we aired on the show live on the radio, an episode on mass incarceration. That same day, we got feedback from someone who is in federal prison here in Lexington, Kentucky. He emailed us with a couple of wonderful messages. Thank you so much, Kris. We really appreciate your messages. Just first, so people know a little bit about this, basically I got an email asking whether I would give permission for someone from federal prison to email me, which is an interesting kind of thing to be asked, I suppose. The answer was absolutely, we want to hear from people. I was very glad to hear from Kris. I’m just going to read a little bit of what we got from Kris. We got a number of substantive emails from him. Thank you so much, Kris. He said, among other things, “I often catch your show and realize the amount of work you et al. put into it. I’m very appreciative. One of my primary goals for my time is studying philosophy.” He says. That’s a very good use of time that you have to think. He goes on to say, “Today’s topic,” obviously today’s meaning last week, on mass incarceration, he says, “Today’s topic obviously visits close to home, as home for me is a federal prison in Lexington, Kentucky. I have many things to share on the topic in anecdotes. Primarily, I have this belief that everyone is imprisoned in some way. Relationships, socio-economic, environment, et cetera. While some may be nice, there is conversely the gilded cage idea, or escapism.” Later he says, “I’ve accepted my situation and my goals somewhat match a cloistered lifestyle.” He wants time to think and be on his own. He says, “However, it could have been much, much different had I had a support network, been allowed to move closer to my family, instead of being sent to a random city simply because my original crime so many years ago occurred in that jurisdiction.”

Thank you for those comments, Kris. I met a number of people, I’ll mention them again in a second, in Parchman prison in Mississippi, and a couple of them told me about how they were there, having committed a crime and been incarcerated in California, and California had such full prisons that they have been sending their inmates to other states. One of those is the state of Mississippi. Anyway, I head you about having been relocated somewhere else, and challenges that raises. He says, at the end of Kris’ email, “I would greatly appreciate any direction as I self-educate philosophically,” he says. First of all, a couple things I want, I want to give a couple comments for this “You Tell Me!” segment. Ordinarily, if we had more time, we would have Anthony join me, and possibly the past guest we had, but we were unable to do that so I’m sorry, you’re going to just hear from me today. But just a couple of comments. First of all, it’s powerful what you said, Kris. Epictetus was a stoic philosopher I’ll say a little bit more about. We’ve had discussion about him on the show in the past, especially episode 5 with Dr. John Lachs. Epictetus thought that all of us, for all of us, we are fundamentally and essentially free in terms of our will, even if our bodies are confined, even if we are highly physically disabled, we may not be able and empowered to do anything that we want, but we can have the will and choose how to feel about things and so forth. That was something very important in the same sense that we are all imprisoned. In some senses, we are also all free, said Epictetus. I’ll tell you more about Epictetus in a moment.

Number two in responding to Kris, thank you so much for these really thoughtful comments on mass incarceration. It’s great that you have been able to study some philosophy and that you have been able to listen to the show. Finally, as far as self-direction and where to go to study some more philosophy, first of all you mentioned in your email to us that you have the ability to read some of Plato’s works, the dialogues of Plato, and you can’t really have a better start than reading some of Plato. There are other exciting places to go and look, and I’ll mention a few thoughts, but the fact that you’re starting with Plato is excellent. Beyond that, let me just give you a few thoughts, because you have asked about some ideas in terms of self-educating in philosophy. There’s a wonderful book that is a novel, and it’s a creative novel in a process of exploring all these different thinkers across the history of thought, it’s a book called Sophie’s World. It’s long and it’s artistic in a number of clever ways, but it’s really a wonderful overview of the history of philosophical thought. I bet you’ll really enjoy it and get a lot of it. Check out, if you get a chance to check out Sophie’s World. You’ll be glad you did, I think. You mentioned also in your email that you’ve been attracted to philosophies of absurdity and existentialism and so on. You probably have read The Stranger, but if you haven’t, you should read The Stranger. Even if you have, it’s a wonderful one to revisit. Beyond that, there are some texts that you may not have had the chance to see. One of them is by Jean-Paul Sartre, if you’re a snooty Frenchman like half of me is, my mother is French, you might say Jean-Paul Sartre. You don’t have to say it like that to be respectable, however. Anyway, he’s got a book, a short essay really, but it’s also in book form. You can get it for free on the internet. It’s called Existentialism Is a Humanism. Check that out. It’s a fun, punchy little read, and it’s got an interesting and iconic example of a young man trying to decide whether a man should stay home and help his mother who needs him or go off to war in France during World War II. Have a look at that, it’s a really wonderful text.

There are a number of other things online that are available if you don’t have the books available to you. But if you do have access to the internet in some fashion, there is the Internet Classics Archive, and you can get digital versions of a number of different books, one of which for instance is Epictetus’ Handbook, another is Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations. I suspect you’ll really enjoy reading those. I mentioned I had a chance to teach a little bit at Parchman Prison in the Mississippi delta, and the inmates there really got into stoicism. It was remarkable and exciting and fun and fascinating. They especially liked Epictetus’ work. E-P-I-C-T-E-T-U-S. Check out Epictetus. It’s called The Handbook¸ it’s also got a weird name called Enchiridion. Look for and I think you’ll find it. Beyond that, most of all, thank you for reaching out to us, Kris, as well as everyone else who has reached out to us. One of the things I want to leave you with, referring to Kris’ example, is the fact that it’s so easy for the majority of us in American society to ignore the people who are out of sight. Out of sight, out of mind.

There’s no one more paradigmatically out of sight than the people whom we put out of sight into prisons. While some people are indeed guilty of having committed some mistake or violation of the law, there are people who obviously haven’t and yet are incarcerated. Most importantly, we’re human beings, and departments of corrections ideally should think about correcting behavior and not just punishing. We want to think about people rejoining society, and thus we want to remember folks who are incarcerated and speak to them and treat them with dignity and humanity, even if they have made a mistake, because that’s part of what it means to be human beings. Anyway, thank you for reaching out, Kris. I have a few more folks who have sent us very quick comments that have been wonderful, a few reviews. One person said, for instance, referring to the episode with Tommy Curry on black male studies, one person said, “It’s officially the most important thing I’ve listened to this year. Already recommended it to friends,” said a listener named Patrick. Another listener named Deonte said “Great interview with Dr. TJC. Really insightful.” That was on Twitter. Another person on iTunes said, “Seems like a great podcast,” he said in capital letters, “GREAT podcast in the making. Eric, thanks for sharing your personal story. Your ability to make bread despite challenges in your life is inspiring. I really enjoyed the first episode of your podcast and I’m looking forward to future episodes.” That was MikeKDidit on iTunes. You can see that review for yourself on iTunes. He may be referring to the pilot season episodes where I talk about my daughter and stoicism and happiness and so forth. If you haven’t checked it out, head to philosophybakesbread.com and you can find those older episodes.

Last but not least, JB424242 wrote “Great show. This is an excellent show,” and that was another 5-star review on iTunes, I was happy to see. I mention iTunes for a couple reasons. One is, please go to iTunes. Please listen to the show and if you enjoy it go to iTunes. We would love a 5-star review there, and my understanding is that it makes a big difference in terms of the algorithms that run our universe and that therefore decide what material to put in front of possible listeners in the future. If you enjoy the show and you want more people to hear it, go fill out an iTunes review, please, and we’ll read you review on the show, especially if it’s a really positive, 5-star review. Anyway, thanks everybody for listening to this perhaps gone too long segment called “You Tell Me!” We really appreciate your feedback, Kris, and everybody who sent us your comments. It means a lot to us. Without further ado, here is our segment called “Know Thyself!” which is part one of the interview that we did with Dr. Danielle Lake.

Dr. Cashio: On today’s show we are very fortunate to be joined by Dr. Danielle Lake. How are you doing today, Danielle?

Dr. Lake: I’m great.

Dr. Cashio: Danielle is assistant professor of liberal studies at Grad Valley State University. Danielle’s work focuses on wicked problems, American philosophy, and democratic deliberation. I’m looking forward to talking about wicked problems.

Dr. Weber: Indeed. Dr. Lake has written numerous pieces on difficult wicked problems, including access to food, healthcare, and other sustainability concerns. She draws on figures in the American philosophical tradition including Jane Adams and John Dewey, among others. She also exemplifies the norms of great public philosophy for which she was recognized with the 2016 John Lachs Award for Public Philosophy for the Society for the Advancement of American Philosophy.

Dr. Cashio: Congratulations. Dr. Lakes’ publications include Institutions and Process: Problems of Today, Misguided Answers from Yesterday, and Sustainability as a Core issue in Diversity and Critical thinking Education, which appears in Teaching Sustainability and Teaching Sustainability in Higher Education, edited by Kelly Parker and Kristen Bartells. That came out in 2012. She also published Restructuring Science: Re-engaging Society in The Pluralist in 2013, and Engaging Dewey in Ethics in Healthcare: Leonard Fleck’s Rational Democratic Deliberation, appeared in Education and Culture Journal.

Dr. Weber: Indeed. Dr. Lake is very productive and is engaged, is not only productive as a scholar in terms of her writing and research, but also in terms of her public engagement, which is something that we’re very interested in both in SOPHIA as well as on this show Philosophy Bakes Bread. In this first segment, Danielle, we follow the important maxim to “Know Thyself!” We want to know whether or not you know yourself and we ask you to tell us about yourself, your background, a bit of who you are, how you came to philosophy, as well as given all that, what you take philosophy to be. Can you tell us about yourself?

Dr. Lakes: Absolutely. First I want to say how much I love that you begin this with asking us about who we are and what we bring to the work we’re doing. I am coming to know myself. It’s taken all of this time, and despite the fact that I’ve been studying it since birth, I’ve always been interested been interested in questions of life, meaning, and death and struggling to find answers for myself. I’m a first-generation college student so I had no clue what I was doing on the college campus and I just wandered around and kept taking all these classes. As interested as I was in philosophy, I was also disappointed at times with how disconnected it was from the problems that I saw all around me and the suffering in the world. I was hesitant to major as an undergraduate in philosophy. We had a major at my university which allowed you to design a program that resonated most with you, so I ended up designing a major called “The examined life” out of Socrates. I took a ton of philosophy, psychology, sociology, and I just wandered around and thought about life, meaning, and death. As I was graduating, my advisor wondered what I was going to do next and I still had no idea. We looked into graduate school and I covered American philosophy, which I see in many ways as a philosophy that studies the problems of life and is more deeply connected to them. So I was able to go on to the University of Toledo and study with James Campbell, who was at the time the president of the Society for the Advancement of American Philosophy and really just start to dig into looking at why we do so badly at wrestling with our shared problems, and what we could do better. From there I went onto Michigan State University, working with Paul Thompson on food ethics and uncovering another way of framing what I was doing around wicked problems, the systemics of crises that we tend to make worse instead of better. Then I started to look at how we could better address these problems. What else could we be doing than what we currently are? What’s behind them and what else is out there to help us wrestle with those issues? [is] my educational trajectory.

Dr. Cashio: In your studies of the examined life, what was it about philosophy that drew you to that? You were a first-generation student, you didn’t think, “Maybe I should go study something and have a big business career?” You’re like, “Nope, gotta think about big problems.”

Dr. Lakes: I’m not sure. I didn’t know what I was doing. I just kept taking the classes that most resonated for me. I didn’t know what I was going to do with them. This internal drive, in fact, in trying to figure out in studying wicked problems, we realize that what we need to bring to the table, that we often don’t, is emotional intelligence and self-awareness. I was trying to become aware of who I am, and wanting to learn endlessly seems to be a part of my inner driving force, and so that was what was motivating the continual exploration of these issues. Then maybe just being really bad at science. (laughter). I somehow avoided taking any lab class in my entire educational career, even though it’s required. My lab class was that we got to go out and look at the start in a telescope. That was my attempt at doing a lab. I think that’s just it, and just happenstance. Other people believing in me, to be honest. I didn’t know if I had anything worth saying. Having professors mentor me and support my work has been critical to being where I am at.

Dr. Weber: It’s definitely the case that even students who can seem very confident in some ways have told me that they have never thought of sending their paper out to a conference. For instance, this very nice confidant athlete in my class, I really encouraged him and others too. He sent out his paper and had it accepted at a conference and just went to present it. He said he never would have imagined. It’s such a difference you can make when you give someone a little encouragement. If only we could systematize that and make sure people regularly got encouragement. Unfortunately, it doesn’t quite work that way.

Dr. Cashio: I could use a bit sometimes.

Dr. Weber: That’s why we call for bountiful praise, by the way.

Dr. Cashio: A pat on the back doesn’t hurt.

Dr. Weber: Please, every now and then we just cry in the darkness somewhere. Anyway. I’m interested about what it is about philosophy that really attracted you. Anthony was asking about the examined life and so on. Beyond encouraging teachers, which are always a good thing, and beyond perhaps abhorring the sciences, what about the content of philosophy was so fascinating to you?

Dr. Lake: Absolutely. The study, the idea that it is the study of wisdom, as I try to understand what any of this means. Who I am, what’s right and wrong. As issues resonate deeply with me, philosophy gave me the tools to better think through and think with others on these issues. To engage in those conversations, whether it’s through reading the text with others or talking with others in my life, it gives us the means to think more deeply about our own struggles, and to more intentionally design our own life and to live a life that’s meaningful. To come to these decisions for myself after having examined them deeply with brilliant thinkers from the past, basically.

Dr. Weber: Right on. Just so you know, we do occasionally like to plug past episodes and we had an episode on first-generation students in philosophy with Dr. Daniel Brunson and Dr. Seth Vannatta a little while back. I encourage people to go listen to that again, because there are special challenges as you mentioned earlier for people first encountering college and not having so many of the cultural support structures that many other people have. We’re going to have a follow-up, by the way, on that topic with other panelists who are on a panel for SOPHIA about this subject. In terms of where we are going about “Know thyself”, and the question about philosophy, I think it’s helpful sometimes to just be blunt and ask directly. What do you take philosophy to be, exactly? You mentioned the study or the pursuit of wisdom, or the love of it. But for the average person who is listening to this, may or may not ever go to college or may have taken a couple courses but didn’t catch much about philosophy, maybe, what is, in your mind, what is philosophy?

Dr. Lake: I’ve said in the past, I go back to the study of wisdom, a fostering our own critical thinking skills, our own dialogue, our dialogic processes, but also now for me, fostering creative capacity as well so that we are able to image other realities in response to our current situations. In many ways what I want it to be is a mechanism for stepping into these problems across our differences, for wrestling with them more honestly. Both within ourselves, the tension, the conflicts within us, but between us and others. I come out of that feminist pragmatist model and for me it’s going to be the philosophy of solving really complex problems with others. It’s going to be a process of engagement.

Dr. Weber: That’s interesting. I think that one of the riches of philosophy is what you just pointed to. You used the word creative, and most people, when we ask about the nature of philosophy don’t go into the creative aspect of it. But there is this something, when you haven’t encountered a philosopher before, and you do, sometimes the idea or the question that they can raise can be profoundly creative. You would never have thought of that, and that can change everything. There is this notion in business that people want folks who think outside the box. The box is convention and habit and so forth. They want people who think. Philosophers are the ones that they should be hiring, it seems to me. If you want people who think outside the box, we would say “What is this box?” I think philosophers can be profoundly creative. I think that’s one of the riches.

Dr. Cashio: You’re right. It’s a side that doesn’t get put up in philosophy very much, that it is a creative, almost artistic activity that is best when you are really pushing the boundaries and imagining new possibilities, new ways of being in the world, new ways of living with other people, new ways of solving problems. I think the best philosophical training really takes off.

Dr. Weber: I have go tone more question before we go to the break, Danielle. As a first-generation college student, I’m sure sometimes you get in your own classroom another first-generation college student who is disinclined from studying more philosophy. How do you convey to that person why it matters to study philosophy, why it might be a really smart idea to study some more?

Dr. Lake: If we don’t know who we are, and we don’t know what kind of a life is meaningful for us to live, then none of that other stuff is likely to matter. We have to pursue ourselves and have the courage to design our own lives. The other piece of it is that a lot of the positions that could be possible for these students in the future aren’t even created yet. I have had some students who basically were able to create their own position with nonprofits fighting over the opportunity to work with them. To imagine your own reality and then to pursue that is philosophy unlike any other discipline is going to give them some of the tools to do that. Maybe the courage. That creative capacity to really think carefully about who they want to be and how they can move forward in the world and create that for themselves instead of trying to find a position that has already been imagined basically, but doesn’t quite fit.

Dr. Cashio: Philosophy is courageously creative. I like that a lot.

Dr. Weber: I do too. After a short break we’re going to come back and talk more with Dr. Danielle Lake. Thanks so much everybody for listening to Philosophy Bakes Bread.

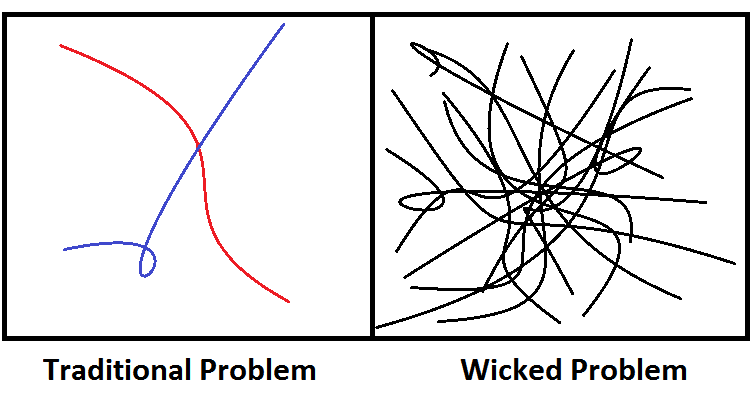

Dr. Cashio: Welcome back to Philosophy Bakes Bread. This is Dr. Anthony Cashio and Dr. Eric Weber and today we are talking with Dr. Danielle Lakes. Dr. Lakes’ work focuses on wicked problems—problems that are deep and intransient. Danielle, I’m going to ask on behalf of my listeners: What the heck is a wicked problem? Can you say more about it? What makes a problem wicked as opposed to not wicked?

Dr. Lakes: If we were going to scale the kinds of problems we deal with in life, we could do that on many levels. We have simple problems, or tame problems that are easily defined, that are static and they dno’t change. You can replicate your answers, you can have a formula, you can apply it. Baking bread is the perfect example. You’re hungry? Gonna bake some bread. Simple problem, simple solution. As you scale up beyond that, you get into complex problems, and as you go beyond complexity, you get into wicked. That would mean that there is no one definition of this problem, it’s chaotic. It’s changing over time. There’s a host of unknowns. We don’t know what exactly is going on, our values, our intentions. We can’t agree even on what the problem is. The stakes are incredibly high on these problems, so that intervening is going to have a lot of serious, unfortunate consequences, but doing nothing does as well. These are going to be problems that we’re confronting around healthcare, around global climate change, around the current food systems that we have. There is no ideal solution. We’re likely to be heading towards an impending crisis, basically. Those are wicked problems.

Dr. Cashio: Why the term ‘wicked’ here?

Dr. Lakes: Good question. It actually comes out of an article from the 1970’s from two city planners who, in trying to intervene and reconstruct what the city looked like, realized that they were confronting problems that were beyond complex. There is a lot of intense disagreement around these issues and a lot of unknowns. They coined the term. It sort of fell away for a while, but in the past 15 to 20 years, natural resource management work and systems thinking have picked it back up and others have as well as another way to talk about our large scale systemic social messes. When I came across the scholarship on that, I thought it was a perfect way of characterizing what I was troubled by.

Dr. Weber: So Danielle, one of the ways of thinking about these problems is that in a sense, you can’t really imagine having anything like a perfect or simple solution. In that sense, these are intransigent problems and when you think about if things can’t get better than a certain level, then they are as good as they can be. That’s one way to think about it. My question is: Is worrying about such problems a kind of idealism, wishing we could solve things that we can’t really be solved? Thus, should we really be worried about them? These are costs of living and it is what it is, and we have to accept them. How do you think about the nature of the intransigence of these problems?

Dr. Lake: I love that question because when I first started exposing students to these problems, that was their exact response. It was either cynicism, like “I give up”, I overwhelmed them and depressed them immediately.

Dr. Cashio: I could see that easily. Throw your hands in the air like, “What? No fixing this!”

Dr. Lakes: The apathy and cynicism. They would give up and be like “This is somebody else’s problem,” or “There’s nothing we can do about it so let’s crawl back into our hole.” I thought this isn’t getting us anywhere. Something about me, I want to dig in but I wanted to encourage them to dig in as well. I’m doing something wrong here because I’m overwhelming, which is in fact one of the symptoms of these types of problems. They do get worse instead of better when we do that. I was trying to figure out why they do turn into crises. Our 2007/8 housing recession in the United States turned into a global recession when we crawled in our hole, we blamed others conveniently for the problem, when we oversimplify what’s happening, we allow that situation to get worse. That means we allow suffering to continue and to grow. That’s a problem for me. I needed to figure out how not to cause that kind of disengagement. It’s also problematic because a lot of us walk into these situations with naïve optimism, assuming we have the answer, which is another symptom of these problems, when we assume we know what’s best for others and that we understand perfectly what’s happening and that therefore they just need to do what we say. I wanted to remove that stance from students but not replace it with that apathy either, or the cynicism. I do think that we can make some difference here in that the suffering of individuals around us does matter and to alleviate those conditions to improve the situation here and now means something. I hope it does.

Dr. Cashio: What do you think we can do then, if we’re not going to be apathetic, or you called it cynicism or the naïve optimism? What do we do then to ameliorate and address wicked problems?

Dr. Lake: That’s exactly where I was taking my dissertation work. How can we do this better? I was looking at different kinds of collaborative problem-solving processes and studying those. Now I’ve been trying to enact them and figure out and build upon them or create my own hybrid models of trying to cope better with these issues. One of the first steps is the willingness to step in. Recognizing who we are and what we bring to the table, our own expertise, our assets. Also our challenges, being willing to recognize what others bring as well. One of the first things I did was ask students to work together and to better understand who they are and communicate that to their team, but also understand those they are working with so we can actually use assets in the room.

The other thing we don’t do so well is that we don’t actually come together across our differences. I am seeing our isolation from one another as a critical root cause of why these problems get worse instead of better. It is very easy to demonize when we are in isolation. It is very easy to say that person or organization is to blame—it’s totally their fault and they must do everything to fix it. It’s a lot harder to say that and think that when you are next to them, in the trenches working with them. Collaborative problem solving processes begin by stepping in, by creating spaces where we come together and understanding our values and trying to find moments of alignment—spaces where we can come to a common agreement about some shared value, and from there leverage that into “What could we do together here and now?” We go back to that creativity piece I was talking about from philosophy. If we could think about not just the current problems, diagnosing them and what’s wrong, but also what we could do about it, what we should do, and what we will do. One of my concerns about philosophy is about if and when it doesn’t push us to “What are we going to do?” We must intervene on these problems because failing to do so means they get worse instead of better. I’m looking at processes like design thinking, strategic doing. I think feminist pragmatism has some core root pieces to it that are helpful for us so that we can leverage into that iterative problem solving process. We never assume that our interventions are foolproof, that they work perfectly, so we always come back to the drawing board. We build upon, we sort of [flex?] to address the situation.

Dr. Weber: Danielle, I’ve heard you mention twice the phrase ‘feminist pragmatism’. For people who have not studied any philosophy, who haven’t been to college and may be listening to this on the air, can you give us a simply, straightforward, everyday-language understanding by what you mean by that term?

Dr. Lake: This comes out of work from Jane Addams in the late 1800’2 and early 1900’s. I’m talking about a commitment to understanding knowledge as something that is a tool for helping us solve problems. The truth is fallible, it’s contingent and it can change. My truth can, based on what’s helping me to live a full life. I see it as a method for addressing our problems. It’s about cooperative action as well. We need to begin by gathering the facts together. When I go out on my own, I often selectively pick out the facts that I want, that resonate with what I want the answer to be anyways. When we gather our facts together, we can come to a better understanding of the situation. I see feminist pragmatism as an undergirding support structure for how to address these issues by encouraging us to seek out difference and listen to others.

Dr. Cashio: The study of wicked problems, then, is studying the problem in all its wicked complexity and also envisioning ways of beginning to try to address or ameliorate these problems, which clearly can’t be easy, or the problem wouldn’t be wicked.

Dr. Lake: That’s exactly right. That’s the trajectory I’ve taken with the scholarship. Studying these problems and then looking at what kinds of processes, what institutional structures or individual habits as well, can help us better address these issues.

Dr. Weber: I want to think about a wicked problem that I have been concerned about and I want to present to you one of the big challenges I see with even trying to think through it and trying to make a difference. In particular, I lived for almost a decade in Mississippi, and one of the obvious problems that hits you in the face is educational failure and frustration. When you think about wicked problems, one answer to the question that you propose when we say “What do you do about something that is this dep, hard-to-change, perhaps intransigent problems?” One answer that seems clear to me is that we make some small, incremental progress. We can make some changes that at least improve conditions at least a little big for some people. When I have focused on that and attended to that, I’m thinking of things like for instance, limited charter schools, not private schools, these are public schools. There are some charter schools in Arkansas that did a lot of good for those in Arkansas. Some people will criticize charter schools on a number of grounds, but the point is that there are tools that people will use to try and make a difference.

There are other examples of good that you can do, for example Teach For America. If you have a legislature that is not funding teachers to the point that brings people in enough, if you don’t have enough teachers, if you were to pay people better you get more teachers. People unwilling to spend enough to get the teachers you need, there are these solutions that critics will call Band-Aid solutions, and some people are furious over the notion of Teach for America, because basically it is a Band-Aid solution covering up the unwillingness of the legislature to spend enough money. I have seen great kids go do wonderful things for people in such programs, and I’m proud of them. On the other hand, critics will just bash the incremental effort at progress. They’ll say that actually people who push for incremental progress are in the way of getting the progress we need, they’ll say. The moderate gets called the problem. Maybe we are. This is my question for you. My inclination as an obvious answer to these enormous, difficult, intransigent problems is to make things at least a little bit better for at least a few people if we can. Then the response might reasonably be “That’s getting in the way of real progress.” What do you think about the issue of partial progress?

Dr. Lake: I’m committed to fallibilism. One of the problems of refusing to play, refusing to step in, refusing to give some new incremental trial something a run, is that we then forego the opportunity to learn from how it goes, to see what are the ripple effects of this intervention. How did it change the system? How did it effect others that I didn’t foresee, that I couldn’t have known about from my own position? My concern is that it’s very easy to critique and tear down. As hard as it is to rebel or remove, it’s even harder to reimagine and to enact what you reimagined and to create a better system instead. What I love about giving new prototypes, new innovations a trial run is that we can learn from how they unfold in that context and then leverage those insights. We can imagine how somebody else might use our initiative, our idea. How they might use it in their own context or reimagine it, or it could be catalyzed out and really cause institutional, instructional change across the board beyond that school or that individual student. It does weigh on me a lot. I have a paper under review now about what it could mean to work with others. What does it mean to work with the enemy? How could I be co-opting myself or contributing to a system that is inherently unjust. I don’t engage lightly. In talking with other philosophers about this as well, I did have the insight that the idea that by not engaging we are somehow outside of the system, is convenient but probably not true. Is there really anywhere to be outside of at this point? At this point, committing I’m myself to stepping in and working with and seeing where that gets us and then leveraging those insights into other avenues.

Dr. Cashio: It would also seem, and correct me if I’m wrong on this, but one characteristic of some of the wicked problems is the isolation that we have, political or ideological isolation. Whatever one side does is always going to get critiqued. Wouldn’t that be an expected, “I’m going to do this and people are just going to be angry about it and there’s literally nothing I can do about it”? You’re not going to please everyone. That seems to be part of the hesitation for people to enter into it. Am I understanding this correctly?

Dr. Lake: Yes, I think you’re absolutely right. As I study this more and more, I realize, in a way I’m calling for virtues that are intentioned in myself and in others. I want us to have enough courage to step in and give it a try, realizing that no matter what we do, it’s not going to go as well as we wanted, it’s going to upset some people, it’s going to cause a lot of backlash. I want us to have enough humility to listen deeply to that backlash, to incorporate it into our next steps. To flux and change the interventions that we’ve been doing. There’s a lot of risky endeavors here. It calls for a lot of courage, but it calls for a lot of listening. That’s why I think the mechanisms here, we need that reflective action piece where we just keep rotating back around. We come together, we reflect on what’s going on and what we should do to intervene, then we act, then we come back together and we keep moving that work forward as a way to see where we can get ourselves.

Dr. Cashio: Courageous enough to be humble.

Dr. Weber: I like that a lot, in fact it makes me feel better. One of the problems I have been worried about. On that note, we’re going to take a short break and we’ll be right back with Dr. Danielle Lake, and thanks so much everybody for listening to Philosophy Bakes Bread.

[Theme Music]

Announcer: Who listens to the radio anymore? We do. WRFL Lexington.

Dr. Cashio: Welcome back, everyone. This is Dr. Anthony Cashio here today with Dr. Eric Weber on Philosophy Bakes Bread. Our guest today is Dr. Danielle Lake. We have been discussing wicked problems in the last segment. This section we are going to talk a little bit more about public engagement work in response to these wicked problems. Danielle, in 2016, your public philosophy was recognized. Congratulations on that, it’s really fantastic. Was this public engagement work, it seemed like from the last segment at least, was it directly connected to your work with wicked problems? How so?

Dr. Lake: As I was finishing up my dissertation, I had the opportunity to redesign and design new curriculum at my university, and out of that, the conclusion of my dissertation is really about my work to try to enact what I was learning in my own life with my students in and outside of the classroom in this community setting. I designed a course called ‘The Wicked Problems of Sustainability’ that was about having students reach out, study these problems not just in the abstract, but go out in our own community and address some of the food justice challenges that we’re confronting in west Michigan, work with local nonprofits, work with schools, work with the enemy, the big food companies, and figure out what we could do to make a difference on these issues. Those kinds of courses from that point on, I had a course called ‘Dialogue Integration Action’ where I had students co-design and co-facilitate community directed dialogues on issues identified by our community. Issues like crime and policing, housing and homelessness. They would facilitate those discussions, they would analyze the findings and put reports together with the community partners, and we would publish those openly. I have a course I have designed called ‘Design Thinking to Meet Real World Needs’ and students use this engagement process where they begin in place, they begin with listening, with mapping the systems that are involved in the problem with conducting that research, with doing outreach to local community members, to local businesses, and really try to innovate around the problem that they are confronting. With that one, we’ve looked at food justice and food insecurity on college campuses, we’ve looked at housing and homelessness in our area in that class as well, and we were looking at the role of satellite campuses in their communities. All of this type of work is aligning my teaching with my research and my service and trying to do work that makes a difference that is publicly relevant.

Dr. Weber: Danielle, you mentioned in passing that major food producers or manufacturers might be the enemy? Can you say a little more about that? How so? What is the problem? What is the wicked problem about food security? What are these big companies doing?

Dr. Lake: One of the concerns that my students really wanted to address was that food companies that are servicing our local schools: Where they buy their food from and why, what they are feeding our kids. The critiques that they had from it in the classroom space was pretty harsh. What I decided to do was reach out to the local companies, the ones that distribute the food to our area, and ask if anyone would come in and talk to us. We did that work and it was a lot harder to…it just transformed uor thinking as we realized that some of these individuals were also struggling deeply with trying to transform those practices from the inside by reaching out to local farmers, by hosting events on the school campuses, by meeting guidelines that change every year, by trying to serve food that is healthy and local but also meets the budget constraints that the schools are under and so forth. To contextualize that problem, to make it real for students, to get out there and really see the reality of what they are confronting, and then also to hear from them that they would love to partner with us, that they are really struggling…again now I don’t want to raise them out of that role of not being held liable for some of these things, that’s the kind of work that I want to do and I think that really made that work real for students and made them want to step into those spaces and support the transformation that we need to see happen.

Dr. Cashio: It was also a good example of working with other people, reaching out to them and realizing, “Oh, you are not a villain!”

Dr. Lake: Or not entirely.

Dr. Cashio: Not entirely. You can at least claim to have good intentions, and we are struggling, so seeing them as a person worth working with…

Dr. Lake: On the flip side of it, another version of that class, we aligned ourselves with a brand new nonprofit that was really struggling and could use a lot of our help and we thought we would be an incredible resource for them. We found out after partnering with them that the model under which they are operating had a lot of assumptions about what the community needed without actually talking to the community first. At that moment, we were midway through the semester, we have to think the students, because I really want to empower the students to do something that they are motivated by. We’re thinking about retreating from that partnership, or dropping out and doing something else, so we had to think about how we could use our concerns in a way that was constructive, and what we decided to do for that community partner agency was go out and actually listen to the community and put a report together on what they most said they needed and wanted, to sort of give that back to the nonprofit so that they were aware as they thought about what practices they needed to implement. That kind of stepping into that tension and trying to figure out how not to walk away immediately but find some common ground or find a way that our own values could still help us be of service.

Dr. Weber: Danielle, you’re talking about a lot of fairly creative things, in terms of what one can do with a classroom. We had some email exchanges before this present conversation, and in that you mentioned that graduate school doesn’t really teach you how to do this kind of stuff. I’m curious about what you would say are some of the challenges or skills you need to do the kind of work you’re talking about, of this shared public engagement together and so on. What surprised you, challenges or needs or skills that you needed to have in order to do this kind of work that you weren’t prepared for in graduate school?

Dr. Lakes: That is such a great question. I would leave class thinking I needed to go back to school and get a counseling degree. They were, in the first couple of times I taught classes like this, I was causing so much stress and anxiety, this is the complete opposite of what students were expecting when they walked into that classroom space. Not only did they have to confront themselves and one another, but I was asking them to confront these huge problems and do so in a public space in a public way. I want students to openly publish their findings. I want them to hold symposiums in the community and share the work they are doing and elicit that criticism in public. I wanted so much from them. They were used to the very traditional way in which classrooms operate, where you submit your paper in private, you get a grade in private with maybe a little bit of feedback, and you move on with your life. It’s all theoretical. It’s all just a 20-page paper. I did think I need a counseling degree. Instead of getting that, I went to our counseling center and said “I need help. I’m doing something wrong.” I reached out to every kind of expert I could possibly think of. Our office for community engagement, nationally, other philosophers doing this kind of work. I pursued facilitation training so I could facilitate these conversations better. I kept digging in and iterating and revising and fluxing my pedagogy, I would say, and operating in that role where I have never been less of an expert in these types of classes and more of a facilitator and a guide of students. That’s one of the things I’ve started to do, I start the semester by trying to make sure that they are more aware of what they bring to the table, who they are, how their disciplinary training is relevant to what we’re doing.

Dr. Weber: So you start with “Know Thyself!”

Dr. Lake: Yes. Absolutely. I love that you’re doing that here. And then know one another. A lot of this is really about relationship building. We need to care enough to listen to others and help them bring themselves to the table. At the same time, we have to be willing to bring ourselves there as well. I think that’s a first step to answering your question.

Dr. Cashio: For our listeners who maybe don’t have experience leading a classroom or teaching a class, giving up a little bit of authority and becoming a facilitator is terrifying. It’s way scarier and much harder in important ways than just lecturing and giving out content, so kudos to you for that.

Dr. Lake: Thank you, and doing it in public as well. I have no idea for sure what my students will do, what will resonate with them. I cant guarantee the quality of their work. I don’t know if this is going to be relevant or meaningful to you as a community partner. Will you partner with us anyway? Going into it, you need deep humility.

Dr. Weber: When you put it that way…

Dr. Lake: Then the opportunities that have emerged, this has led me to want to co-author with my students, to co-author with my community partners, to empower their voice to say what they have gotten out of these experiences and why they are relevant, instead of just me saying it.

Dr. Weber: One of the things that strikes me about what you have said though, is that a lot of what you have done has involved making students, maybe some other people, pretty uncomfortable. At the same time, isn’t that exactly what the philosopher, as gadfly, as the bug that would sting the horse in the ass if the horse is the mind, to get the mind racing. That’s the gadfly, that’s the metaphor for the philosopher that we talked about in the first episode with Anthony. Isn’t that what we’re supposed to be doing? And yet you’re telling us that even in PHD programs in philosophy we are not teaching that? How do you make sense of that? Aren’t we supposed to sting the horse in the rear end, to make us uncomfortable so we have to think hard.

Dr. Lake: I think it’s something about how the PHD process works for most disciplines, that you continue to specialize, specialize and sub-specialize and the group of others that you engage as you do that work becomes more narrow and narrow and narrow, so that you know how to talk to them but you don’t know how to be a gadfly to others in an effective way. I’ve been horrified to realize that if I want to do publicly engaged work, I don’t necessarily always know how to talk to the public. I’ve been trained to talk in a certain way and I have been trained to write in a certain way. How do I write for a public audience? It’s pretty hard. Trying to teach myself all of these other skills that I wish we would have gotten a some point in our lifelong educational career.

Dr. Cashio: Eric and I have been teaching ourselves how to do that public conversation, just by doing this radio show. We didn’t know all the thing we assume someone knows about. We have to back up and ask what we mean by like, feminist pragmatism in the last segment. That’s a good example. Can’t just assume people know what we’re talking about.

Dr. Weber: We have let ourselves be comfortable enough with screwing up in public so that we can learn and try to do it a little bit better each time, I hope. It is terrifying to do that kind of thing. In fact, this notion of, I think you can be a gadfly in the classroom, but there’s something about, if you want to show that this matters, do it out in public. I have been reluctant. I work with students on getting them to write for public outlets, but I don’t require that they submit them because there is this kind of, why you shouldn’t make your students’ grades public. There is kind of like this private element of education, and yet my goodness. We need public engagement. We need to teach people these things. At least an element. Maybe their grade isn’t public but we have to do some of these things in public. I think it’s fantastic that you’re doing it. Honestly, my sense of it is, at least in philosophy, that’s very rarely done. I wonder whether you have any particular models. You mentioned there are people out there doing this kind of work. Who is doing this work and what are they doing?

Dr. Lake: Particular names are coming to my mind in this moment, but at the last Teaching For Philosophy conference I was running into others that were doing work like this. It often seems to be those who are newer to teaching philosophy, or maybe younger in their careers. I encounter more female philosophers doing this work, thus far, than men. On the other hand, it’s risky to do that work when you don’t have tenure yet, I believe. One of the things I have been interested in doing is looking at how the system operates to make this kind of work challenging. In trying to uncover models, I see Jane Addams as somebody who is doing this work so incredibly well that It is even controversial to call her a philosopher. Some people don’t see her as a philosopher. They see her as a sociologist or a charity worker. I see her as a publicly engaged philosopher working with many diverse populations to make a difference in her community and across the world.

Dr. Weber: Here, here. That’s a wonderful example. That is a fantastic point to end on. Everybody, we’re going to be right back with one more segment with the fantastic Dr. Danielle Lake and my co-host Dr. Anthony Cashio and me, Eric Weber, with Philosophy Bakes Bread.

Dr. Cashio: Welcome back everyone to Philosophy Bakes bread. This is Dr. Anthony Cashio and Dr. Eric Weber and today we have had the tremendous privilege of talking with Dr. Danielle Lake about wicked problems. In this last little segment we’re going to have some big-picture questions, some light-hearted thoughts, maybe bake some bread, and we’ll end with a pressing philosophical question for our listeners, as well as some info about how to get a hold of us at the end of this show. Danielle, I’ve got a question for you. Hopefully this will go out to a large number of people who are listening and, unfortunately, not everyone is lucky enough to be able to take classes with you. Is there anything that an individual can do in their own life and how their thinking and living with others to begin to address these wicked problems without getting crushed underneath them?

Dr. Lake: I really love environmental philosopher Kristin Shrader-Frechette’s phrase or term ‘open-minded advocacy’. I think we need to have the courage to advocate for what we see for others, for the suffering and struggle around us but we also have to do so in a way that is open to the ideas of others. Just to initiate these conversations with anybody around us, to step into those differences when you know that you care about someone and you disagree on these issues, how could you invite them into a space and listen more deeply to what they have to say and then ask them to listen to you as well and start to move together along those lines? How could you, also, at the end of the conversations, think about how you can leverage what you’re learning into something next into something new. Everyday what could we do? That reflective action piece of moving ourselves forward in a way that shifts these problems for those in our lives and those in our communities.

Dr. Cashio: Moving forward really does begin with knowing thyself and then moving forward. Sounds good.

Dr. Weber: Any last big-picture thoughts or comments you want to leave people with about wicked problems in this world, Danielle?

Dr. Lake: Yeah, I really would love to see us move the way we engage these issues and the way we engage in education so that we’re not asking students to consume the knowledge that we as instructors or as experts, as Ph.D.’s have to offer, but that we start to move from that model to asking them to produce knowledge and to produce knowledge that is useful. I want them to not only generate information, because if it just sits somewhere it doesn’t do anything, but I want them to use it. If we could better link the knowledge that we’re creating to the situations we’re trying to address, we could really make a difference in our communities and in our lives. In order to do that we need to start getting out. In the design of or classes, if we are talking to instructors here, if they designed those classes with community problems in mind, we could design projects that really make a difference here and now, we could empower students not just to consume information, but to produce something of value to the community, and we would be creating future leaders.

Dr. Cashio: Alright Danielle. We ask every one of our guests the same question. It’s the title of the show. What do you think, does philosophy bake bread? Does it not bake bread? I think we can kind of guess your answer on that. Assuming you think philosophy bakes bread, that it’s quite practical, and I think you’ve made a case, what would you say to people who would argue that it doesn’t, that it’s useless or just a fun, leisure time thought experiment that ultimately does nothing.

Dr. Lake: I have to say I’m honestly sympathetic to the skeptics here because I had that same concern about philosophy. If all it is is ruminating alone in an ivory tower, there might be something unethical about that at times. At its best, it does and should, and beyond that I want to say I absolutely love this question. I’ve been obsessed with bread my entire life, I bake it a couple times a week, and I would never let the ducks eat it. (laughter). Philosophy needs to bake bread and I hope it will continue to do it more so.

Dr. Weber: Right on. The French have a bunch of recipes that are all about taking advantage of old bread, ‘pain perdu’. A lost bread, or when you have a French onion soup, that’s why you have French onion soup, is because your bread is hard. You throw the bread in the French onion soup and all of a sudden it’s fantastic again.

Dr. Cashio: Stale bread for the French toast.

Dr. Weber: There’s a reason there’s so many recipes like that. Exactly.

Dr. Cashio: For our listeners, it’s getting close to dinnertime here.

Dr. Weber: Danielle, as you know, we want to make sure people see not only the serious side of the incredible weight of wicked problems, but also the lighter side of philosophy, that we like to have a little fun too. Inquiry can be fun and not only just sort of terrifying. Therefore, we have a segment that we call ‘philosophunnies’. Therefore, we have a segment that we call ‘philosophunnies’. I have a little recording of my son saying the word and I think it’s funny so we’ll probably plug it here.

Dr. Weber: Say ‘philosophunnies’

Sam: Philosophunnies!

(laughter)

Dr. Weber: Say ‘philosophunnies’

Sam: Philosophunnies!

(child’s laughter)

Dr. Weber: We would love to hear whether you have either a funny story about philosophy or about wicked problems or a joke that you would like to tell, again either about philosophy or about wicked problems, or any kind of issue. Have you got a joke for us or funny story?

Dr. Lake: Yes, with your help, I have to say that this segment caused me the most angst and I am not funny in any way. (laughter). We’ve uncovered, I think, a really great joke that aligns with our conversation from the past 40 minutes or so. I can give that to you. The question is: How many pessimists does it take to light an oil lamp? The answer is that it takes none, because it is going to be a waste of time, since the lamp will burn out soon enough. This is perfect because again, if we don’t even try, we’re going to get nowhere. That is the exacts opposite of what I’m hoping to foster in my students, despite the overwhelming weight of the struggles that we’re confronting right now, in the world.

Dr. Weber: Right on. Anthony and I dug up a few jokes, not necessarily referencing wicked problems, but about some of the wicked problems out there like climate change and so forth. Anthony, you got one for us?

Dr. Cashio: Oh sure. You know, I’ve been thinking. Every time I hear wicked problems, I always hear it in the Bostonian, New-England accent: “That’s a real wicked problem you’ve got there.” (laughter). Why are pirates so eco-friendly?

Dr. Weber: I don’t know. Why are pirates so eco-friendly?

Dr. Cashio: They always follow the three ‘Arrrrgh’s. I’m embarrassed for myself for saying that.

(laughter)

Dr. Weber: Question: How do Prius owners drive? The answer is: One hand on the wheel, the other hand patting themselves on the back. In fairness, I drive one of those, so I think I can tell that joke just fine.

Dr. Cashio: We must practice economy at any cost.

(laughter)

Dr. Weber: That was one of the jokes, Danielle. Last but not least, let’s see. This one’s about people unable to hear each other, or unable to listen, which isn’t quite the same thing. Anyway, we like this joke. There’s three retirees, each hard of hearing. They were sitting together on a park bench. One said, “Sunny today, isn’t it?” the other one says “No! It’s Thursday!”, and the third retiree jumps in and says “Me too! Let’s have lemonade!” (laughter).

Dr. Cashio: What? Alright, we’ll go with that one.

Dr. Weber: We need a rimshot, I think, for a little help.

(rimshot, laughter)

Dr. Cashio: Last but not least, we do like to take advantage of the fact that we have access to all of you with powerful social media just in our pockets and at our fingertips. We want to have two-way communication with our listeners. We really want this, so we want you guys to be contacting us so we can respond to you and have this conversation that we’ve been talking about today. We want to invite our listeners to send us their thoughts about these big questions that we raise on the show.

Dr. Weber: Exactly. Danielle, in light of that, we want to ask you whether you have a question for us to ask our listeners for our segment that we call “You tell me!” Have you got a question that you propose?

Dr. Lake: I absolutely do. What I want to know is what they can do today, int heir own life, witht heir loved ones, with co-workers, within their own community, to step into the challenges that we’ve been talking about, to step across those differences and those divides, the isolation that we have, and to engage in and advocate for change that they want to see in their own lives.

Dr. Weber: Right on. What can you do in your life, day-to-day, to reach across the divides, to contribute in some fruitful way, to addressing some of the wicked problems that we face.

Dr. Cashio: Thanks for listening to this episode of Philosophy Bakes Bread: food for thought about life and leadership. We your hosts, Dr. Anthony Cashio and Dr. Eric Weber, are really grateful today to have been joined today by Dr. Danielle Lake. We hope you listeners will join us again. Consider sending your thought about anything that you’ve heard today that you would like to hear about in the future, or about the specific questions that we have raised for you.

Dr. Weber: Indeed. Once again, you can reach us in a number of ways. We’re on twitter @PhilosophyBB, which surprisingly stands for Philosophy Bakes Bread. We’re also on Facebook @PhilosophyBakesBread, and check out our SOPHIA’s Facebook page while you’re there, @PhilosophersinAmerica.

Dr. Cashio: You can of course, email us at philosophybakesbread@gmail.com, and you can also call us and leave a short recorded message with a question or a comment that we may be able to play on the show, reach us at 859-257-1849. That’s 859-257-1849. Join us again next time on Philosophy Bakes Bread: food for thought about life and leadership.

[Outro music]