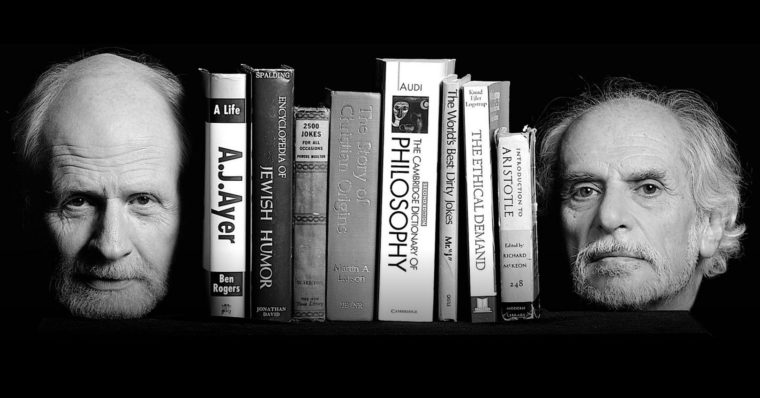

In this seventeenth episode of the Philosophy Bakes Bread radio show and podcast, co-hosts Dr. Anthony Cashio and Dr. Eric Thomas Weber interview the New York Times Best-selling authors of Plato and a Platypus Walk into a Bar, Tom Cathcart and Daniel Klein.

Danny Klein has written comedy for Lily Tomlin, Flip Wilson, and others, and published scores of fiction and non-fiction books—from thrillers to entertaining philosophical books, such as his London Times bestseller, Travels with Epicurus, and his most recent book, Every Time I Find the Meaning of Life They Change It.

Tom studied theology and managed health care organizations before linking up with Danny to write Plato and a Platypus, Aristotle and an Aardvark, and the Heidegger and a Hippo books. Tom is also the author of The Trolley Problem, or Would You Throw the Fat Guy Off the Bridge? an entertaining philosophical look at a tricky ethical conundrum.

Listen for our “You Tell Me!” questions and for some jokes in one of our concluding segments, called “Philosophunnies.” Reach out to us on Facebook @PhilosophyBakesBread and on Twitter @PhilosophyBB; email us at philosophybakesbread@gmail.com; or call and record a voicemail that we play on the show, at 859.257.1849. Philosophy Bakes Bread is a production of the Society of Philosophers in America (SOPHIA). Check us out online at PhilosophyBakesBread.com and check out SOPHIA at PhilosophersInAmerica.com.

(1 hr 10 mins)

Click here for a list of all the episodes of Philosophy Bakes Bread.

Subscribe to the podcast!

We’re on iTunes and Google Play, and we’ve got a regular RSS feed too!

Notes

- Epicurus and Epicurean Philosophy on the Web.

- Samuel Beckett, Waiting for Godot (New York: Grove Press, 1954).

You Tell Me!

For our future “You Tell Me!” segments, Tom and Danny proposed the following question in this episode, for which we invite your feedback: “Why are there things that are, rather than nothing?” What do you think?

Let us know! Twitter, Facebook, Email, or by commenting here below!

Transcript

Transcribed by Drake Boling, July 8, 2017.

For those interested, here’s how to cite this transcript or episode for academic or professional purposes (for pagination, refer to the printable, Adobe PDF version of this transcript):

Weber, Eric Thomas, Anthony Cashio, Tom Cathcart, and Daniel Klein, “The Wisdom in Humor,” Philosophy Bakes Bread, Transcribed by Drake Boling, WRFL Lexington 88.1 FM, Lexington, KY, April 24, 2017.

[Intro music]

Announcer: This podcast is brought to you by WRFL: Radio Free Lexington. Find us online at wrfl.fm. Catch us on your FM radio while you’re in central Kentucky at 88.1 FM, all the way to the left. Thank you for listening, and please be sure to subscribe.

[Theme music]

Dr. Weber: Hey everybody. You are listening to WRFL Lexington, 88.1 FM, all the way to the left on your radio dial. It is a little after 2 PM and you’re here with me, Dr. Eric Weber. We’re about to start our very special episode today of Philosophy Bakes Bread. On today’s show, we have a laugh a minute because we have the best-selling authors of, among other books, Plato and a Platypus walk into a Bar. I’m going to let the show speak for itself. I hope you all enjoy and thanks everybody for listening to WRFL Lexington, 88.1 FM on your radio dial. This is Eric Weber. Thanks for listening.

[Theme music]

Dr. Weber: Hello and welcome to Philosophy Bakes Bread: food for thought about life and leadership, a production of the Society of Philosophers in America, a.k.a. SOPHIA. I’m Dr. Eric Thomas Weber.

Dr. Cashio: And I’m Dr. Anthony Cashio. A famous phrase says that philosophy bakes no bread, that it’s not practical. We here at SOPHIA and on this show aim to correct that misperception.

Dr. Weber: Philosophy Bakes Bread airs on WRFL Lexington 88.1 FM, and is recorded and distributed as a podcast next, so if you can’t catch us live on the air, subscribe and be sure to reach out to us. You can find us online at philosophybakesbread.com We hope you’ll reach out to us on any of the topics we raise, or on any topics you want us to bring up. Plus, we have a segment called “You Tell Me!” Listen for it, and let us know what you think.

Dr. Cashio: You can reach us in a number of ways. We are on twitter as @PhilosophyBB, which, stands for Philosophy Bakes Bread as always. We’re also on Facebook at Philosophy Bakes Bread, and check out SOPHIA’s Facebook page while you’re there @PhilosophersInAmerica.

Dr. Weber: Last but not least, you can also email us at philosophybakesbread@gmail.com, or you can call and leave a short, recorded message with a question, or a comment that we may be able to play on the show at 859-257-1849. That number is 859-257-1849.

Dr. Cashio: On today’s show, we are very fortunate to be joined by two guests, Daniel Klein and Tom Cathcart. How are you guys doing today?

Thank you for joining us. Danny and Tom are the authors of the New York Times bestseller Plato and a Platypus Walk into a Bar, Aristotle and an Aardvark Go to Washington, Heidegger and a Hippo Walk Through Those Pearly Gates. There’s a lot of movement going on in these books. Among other books! Many other books. Today we will be talking about the wisdom of jokes and learning how to philosophize with a little bit of humor.

Dr. Weber: Danny has written a comedy for Lily Tomlin, Flip Wilson and others, and published scores of fiction and nonfiction books, from thrillers to entertaining philosophical books such as his London Times bestseller Travel with Epicurus, and his most recent book, Every Time I find the Meaning of Life, They Change It.

Dr. Cashio: Every time? That’s a bummer. Tom studied theology and managed healthcare organizations before linking up with Danny to write Plato and a Platypus and Heidegger and a Hippo books. Tom is also the author of The Trolley Problem, or, Would You Throw the Fat Guy Off of The Bridge?… What a question … An entertaining philosophical look at tricky ethical conundrums.

Dr. Weber: Gentlemen, we are so glad to have you on the show. Thank you so much for joining us. We call this first segment “Know Thyself”, so we ask you to tell us about yourselves, about whether or not you know yourselves, and how you came to philosophy, as well as given what you know of yourselves and so forth, what philosophy means to both of you.

Klein: You want to begin, Tommy? You’re the taller one. I don’t want to talk down to you though.

Cathcart: Who am I? I grew up in West Virginia, near the Kentucky Border, actually. Actually, I was born in Pennsylvania, moved eventually to Massachusetts, where I went to high school. A suburb of Boston, and then went off to Harvard. The first day of my freshman year, I met Danny, who was standing in my room. We weren’t roommates but he was standing in my room when I walked in the door. It was a home invasion or something. He was there. We became fast friends.

Cathcart: This was 60 years ago.

Dr. Weber: Did you ever find out what he was doing in your room?

Cathcart: No. He won’t tell me. (laughter)

Klein: Still holding out for the ransom. That’s all I can say.

Cathcart: So you guys were just teenagers in 1957, right? My freshman year, there was a general education requirement in the humanities, the social sciences and the natural sciences. For my humanities one, I picked something called Humanities 5, which was titled “Ideas of man and the world in Western Thought”. It was a bunch of different stuff. Some Greek tragedies, some Shakespeare, but mostly it was philosophy. Particularly, after we got into the modern period, Descartes, Hume, we read Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion, at that point I was headed for the ministry. Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion was a bit of an eye opener for me.

Dr. Cashio: I taught that today in my class. No joke.

Cathcart: I was hooked on philosophy right away. I declared it as my major at the beginning of my sophomore year. Danny started majoring in something else, but eventually he came onboard, mostly because of my enjoyment of it, right Danny?

Klein: Absolutely. Tom was a big influence on me. I was much more floundering. I didn’t want to be a minister, in part because I wasn’t Jewish.

Cathcart: Come on over. We accept anybody.

Klein: I was floundered. I thought that like a good Jewish boy, I should become a lawyer, so I started studying that stuff. I hated it. Then I studied psychology and something in me was already philosophical. It seemed to me that it was non-rational, most of psychology. I still think that. Tom and I were hanging out all of the time and I would get excited by the stuff he would bring back from the classroom. I took that same course, that humanities course, and it knocked me through a loop. I said this is it. MY father asked me how I was going to make a living with it. I told him, “50 years later Tom and I will write a bestselling book.”

Dr. Cashio: Think of it in the long term, dad.

Klein: He died disappointed in me, but that is another story. (laughter)

Dr. Weber: Tom, I am curious. You were talking about Hume and something absolutely hooked you, you said, about this course. What is it about your study of philosophy that hooked you? What is it about these thoughts or these thinkers most compelling?

Cathcart: Some of the stuff spoke to me as a person, like both Danny and I enjoyed reading the existentialists. I took a course in existentialism. But some of it was such an intellectual challenge, I just liked playing with the ideas. Hume’s argument against natural religion, or even WV Quine was on the faculty at Harvard at the time. Danny and I both took his course on his book Word and Object.

Dr. Cashio: You got to take a class with Quine? I’m a little jealous. That’s awesome.

Klein: He was very cute and the girls loved him. He played jazz piano in a club in Harvard square. He was something. I didn’t understand a word he said but I really admired him. I’m an example of someone who doesn’t get it but still likes philosophy. Quine would get up there with a proposition, he’d say, “If A but not B only if and only if…G H and Y”, and this house of cards would then collapse and I wouldn’t…Tom, who is smarter than I would be going, “Yeah, that’s terrific! If and only if…”

Cathcart: You’re exaggerating.

Klein: I guess that’s the answer to your question. It was both the existential stuff but also the intellectual challenge of particularly challenging my own beliefs. I came in as a very naïve minister-to-be. That’s what brought the puzzle aspect and the existential aspect together, was that I enjoyed asking myself those questions and trying to find my way out of those boxes.

Cathcart: Can I tell my favorite, speaking of Hume, empiricism joke? This guy comes home early from work and walks into his bedroom, and there his wife is naked in bed with his best friend. His best friend sits up and he says, “Sam, before you say anything, what are you going to believe—me or your eyes?” (laughter) Very old joke. It’s become kind of a meme today for obvious reasons.

Dr. Weber: Well Daniel, let me follow up and ask you. In engaging with these ideas that you were talking with Tom about, what if anything, in particular hooked you to keep you going in philosophy and really kept you in it?

Klein: I have always been naïvely philosophically minded. I’ve always wondered since I was a little kid about the big questions, the big unanswerable questions about the meaning of it all and I’ve been preoccupied with mortality since I was a little kid. It was not, maybe part of it was rebelling. I came from a science home. My dad was a big scientist. My older brother was a scientist. I don’t know if I had any talent, but I just wasn’t drawn to it. I was put down all the time for having these unanswerable questions. They were only interested in scientifically answerable questions. I remember, Tom and I took a course in theology from Paul Tiller. It’s amazing, the geniuses on parade at the time. When I was studying government, my teachers were Henry Kissinger and, who is that Slavic guy who is forgotten…where was I?

Dr. Weber: What hooked you in philosophy?

Klein: When we took that Paul Tiller course, it was hard for me, but I liked it. It was existentialist, it wasn’t dogmatic in the way I thought of religion being dogmatic, or the way my father thought of religion being dogmatic. When my father saw, when they would send home to the parents the courses you were taking, he says, “You’re taking a course in theology? I’m paying all this money…” What did Harvard cost then? $1,800. He said, “I’m paying all of this money so you can learn this bull…” Some part of it was rebellion, I guess is my point. I wonder about things. I’m a wonderer.

Dr. Cashio: How can you not?

Klein: It’s easy for my dad.

Dr. Cashio: Building off what you were just saying, Danny, we always like to ask our guests my favorite question: What is philosophy? Someone who hasn’t taken a philosophy course before, they come to you. You say, “I write books about philosophy,” they say “What is that? What is philosophy?” What do you say to them?

Klein: In common day parlance it would be called the big questions: Is there a meaning to life? Is there a God? How do you know what is right and wrong to do? Are there other kinds of consciousness that have equal validity to our everyday consciousness? That’s one I think about a lot. Tom and I want another thing. We’ve been friends, very close friends, for all these years. Another think we do is experiment with psychedelic drugs, into our old age. Part of it is just because it’s a lot of fun. But the other reason is because we’re interested in alternative consciousness and if it might tell us something that everyday consciousness does not, which seems like a similar program to what philosophy does also.

Dr. Weber: Tom, what would you say to somebody about the nature of philosophy? What is this thing that you write about?

Cathcart: That pretty much does cover the first 20-something centuries of philosophy, starting from Plato. More recently, as you guys know only too well, the questions have become way more technical. The structure of language and logic, different modes of reasoning and so forth.

Klein: I don’t think those bake bread. They don’t even make matzah! (laughter)

Cathcart: I would recommend to a certain kind of mind, a certain kind of questioning nature out there that just wants to know about how logic unfolds, how to construct a rational argument, how to destroy a rational argument. All of those things are very interesting to me too. It is the big questions, plus it’s the little questions, and more recently it’s a lot of the little questions. I like them both. I’ve enjoyed reading both.

Klein: I don’t like the more esoteric questions, largely because I can’t follow them. I’m still stuck on the big basic questions. One thing I like, it turns out I like the Greeks a lot. It turned out later in life, when I spent time living in Greece and learning a little bit of the modern Greek language, and hanging out with Greek people, they still talk philosophy [in taverns?] It’s still part of the way it was in the ancient days, is still true in the terrace. My impression, there was a time in Greece where Epicurus had his garden up on the hill and people gathered from all walks of life. Courtesans came; it was already a novel idea to have women joining the conversation. They talked philosophy. Ordinary people talked philosophy. Socrates was yakking it up around the block there, and Aristotle had his Lycium there all at the same time. People are talking philosophy in the fish market, and I liked that. Not to the same extent, but when I spend periods of time in Greece, I’ll find myself with a fisherman and he’s saying “I wonder about it all.” I see that less in this country.

Cathcart: I would say one more thing about my attraction, and this might be true of you too, Danny, of philosophy. It influences how you think about everything else. You become a more critical thinker when you read social theory or when you read politics of the day, or when you read the social issues of the day. You look at them in a more surgical way, a more penetrating way. You raise more questions for yourself than you would have if you hadn’t studied philosophy. I don’t know, because I haven’t done both things—both studied it and not studied it. But I think that’s true. You ask more penetrating questions of yourself and the world.

Klein: You ask the substrata questions. Recently, I wrote a piece for a local paper before the presidential election. I started collecting social scientists’ theories of the rise of Donald Trump, and I compiled a list of ten of them, all from reputable guys. They all made equal sense, and I started to think, “This is not good science”. My suspicion that the social sciences is full of crap is being validated right here in front of me.

Dr. Cashio: You hear that folks? You know where to write in.

Klein: I took that point of view. One reader wrote back “Well maybe they are all true.” I decided not to answer that one. (laughter)

Cathcart: I think I was that reader, actually. (laughter)

Dr. Weber: Thank you so much, gentlemen. We’re going to come back after a short break. Thank you, everyone, for listening to Philosophy Bakes Bread. We’re talking with Tom Cathcart and Danny Klein. Thanks so much, everybody. We’ll be right back.

Dr. Cashio: Welcome back everyone. This is Philosophy Bakes Bread. This is Dr. Anthony Cashio here with my co-host Dr. Eric Weber. It is our privilege to be talking with two esteemed gentlemen, Danny Klein and Tom Cathcart. Today we are discussing the wisdom in humor. We decided to have a very serious conversation about this. Tom and Danny, you’re probably best-known for your bestselling books, Plato and a Platypus Walk into a Bar, and Heidegger and a Hippo Walk Through These Pearly Gates. Before you wrote these books, I think you were working in television, and had other lines of work. When did you guys come together and say, “You know what? We should write a book. The world needs a philosophy joke book.” What was the thought process there? How did you come to this?

Klein: We have a very clear answer to that. It begins with me telling Tom the following joke on the telephone. I should add that I can’t remember anything except jokes. I’m almost 78 years old. I can remember every joke I’ve ever heard.

Dr. Cashio: That’s a great skill to have.

Klein: I can’t remember my first wife’s name. Do you remember? What was it? She was short, very short. Anyhow. I say to Tom. It’s got the same setup. A lot of jokes have this same setup because it’s an anxiety-provoking situation. This guy is in bed with his best friend’s wife. They hear the car pull up in the driveway, the husband. So the guy jumps out of bed. His name is Sam. He jumps out of bed stark naked and hides in the closet. Just a moment later, the husband walks in, opens the door. He goes to the closet to hang up his coat, and he sees Sam standing there stark naked and he says, “Sam, what are you doing here?” and Sam replies, “Everybody’s got to be somewhere!” (laughter)

Cathcart: Old joke…years ago on the Ed Sullivan show. I remembered it one day and he told me. I saw that mic, which I hadn’t seen when I was 10 years old. Danny told me, and I said there is a philosophical angle to that joke. And he said, “Is it?” and I said, “The guy in the closet is answering from on high. He’s answering from the absolute perspective. He looks at the screen of history and he says that everybody has got to be somewhere. But that isn’t the questions the husband is interested in. The question he’s interested in is the existential question, “What are you doing here. Of all people in my closet…

Klein: You said the absolute perspective is Hegelian. So he said it’s a Hegelian answer to an existential question. I remembered just enough philosophy to say, “By golly, you’re right!”

Cathcart: So Danny says, “There’s a book in this!” and I said yeah right. There’s probably four jokes in the world that say anything about philosophy. Danny said, “No there are hundreds of them.” I said “No that’s crazy.” Meanwhile, Danny has been writing books for like 20-30 years before that. He often says, “There is a book in that,” and he’s usually right. I had a little faith that he maybe knew what he was talking about. We went away to a motel in Massachusetts and we took a stack of philosophy books and a stack of joke books, and at the end of the weekend I said, “Geez, I think you’re right. I think there are hundreds of them. Turns out, there are 142, actually.

Dr. Cashio: No more no less?

Klein: There may be more, but we counted off at 142. We wrote the whole book on speculation because it’s not the kind of book you can sell in a two-page proposal. We had a ball writing it. We had so much fun. Then we presented it to my agent and 40 publishers rejected it. Virtually all of them said that it’s so clever, and this will interest you guys, but nobody gives a flying hoot about philosophy. So I’m sorry. Thanks but no thanks. 41 and 42 both came in. Workman Publishing and Abrams. Remember Workman, they gave us some ideas about how to develop it. Then Abrams came in and Workman dropped out. We got an advance enough to cover our phone bill. I think it was three or four weeks after it came out we were on Times bestseller list.

Cathcart: We got very lucky. There is one dramatic moment in the story, and that is that we were on radio, Weekend Edition with Liane Hanson. Our publicist or somebody had sent her a copy of the book and for some reason it tickled her so she had us on. We recorded the show on a Friday, and it was being aired on Sunday morning. Before we went on, I thought in those days all you could see on Amazon was your rank. I went on, maybe that’s all you can see on Amazon. I went on Amazon and we were number 2,234 in the list.

Klein: Which is actually high.

Cathcart: Yeah, our publisher was very pleased. I thought 2,234. We’ll see if this makes any difference. So about a half hour after we got done, I looked again and we were number three.

Klein: A friend of mine took a picture when we hit number one. He took a screenshot, I’ve heard that’s called.

Dr. Weber: I think a lot of philosophy books are in the 5 million or 6 million, in terms of rank.

Dr. Cashio: You get lucky if two people read it.

Klein: Can I try a funny family story? I have a daughter who is in the publishing business and she is my ownly child. Some fathers, insecure fathers, always trying to impress her, and I’m never successful. At one point, the book got translated in up to 30 languages, and it got translated in all the western European languages except the Scandinavian countries and many eastern European ones. WE got an email or a call that said we had made the bestseller list in Bulgaria. I, of course, immediately am on the phone with my daughter in New York. I say, “Guess what? Your dad has a book on the bestseller list in Bulgaria.” She said, “That’s great dad. You must have sold seven books!” (laughter)

Dr. Cashio: She gets it from you, huh?

Dr. Weber: One of the issues of humor is that someone’s gotta be the butt of the joke sometimes. One of the traps that there can be is to be demeaning or dismissive. Our question then, is: How do you avoid falling into the trap of harsher, some people can laugh meanly at others? The jokes we get from you guys really avoid those kinds of mean-ness.

Klein: Not entirely.

Dr. Weber: That’s true. It’s hard to avoid them entirely.

Cathcart: We wrestled with this a lot. WE had a joke in the book that actually could have been easily taken as being anti-Semitic. In fact, that Danny’s name was Klein probably helped us with that. But then, at the end of the joke, we said, “Is this joke anti-Semitic, or is it making fun of anti-Semitism?”

Klein: Yeah, people who stereotype. I’ll tell the joke. You be the judge. Two old Jewish guys pass by a church. The church has a sign up. It says, “Convert and get $1,000.” They talk it over. One guy goes in, and his friend waits outside. He waits an hour, he waits two hours, he waits three hours. Finally his friend comes out and he says to his friend, “So, did you get the $1,000?” and his friend said, “Is that all you people think about?” (laughter) There are levels to that joke. As soon as the guy is converted, he becomes a stereotyper. That’s the joke, really. Then we got hung up on, Sardar jokes, which are wonderful in epistemology. Sardar jokes, and we didn’t even know this at the time. Somebody turned us onto these jokes. They are a sect of Sikhs. Every country has them, every culture has them, has some element of this society that is supposedly stupid. We have blonde jokes and Polish jokes. When I was a kid they were called Swedish jokes. The Jews have one called “The wise men of helm”. The wise men of helm are so literal-minded that they are stupid. The Sardar are similar to the wise men of helm. They are very literal-minded to the point of absurdity.

Can I tell a Sardar joke? So a Sardar is on the train going to Mumbai, and he wants to take a snooze. So the only other guy in the compartment there, he says, “I’ll give you a hundred rupees if you wake me up when we approach Mumbai.” The guy said, “Sure, a hundred rupees? You bet!” The Sardar goes to sleep and the other guy thinks, “Geez, a hundred rupees? That’s an awful lot of money just to wake him up. I happen to be a barber. While he’s sleeping I’ll give him a little haircut.” He takes off his turban and gives his a nice crew cut and puts the turban back on. He says, “While I’m at it, I think I’ll do his beard.” He shaves off his beard, gives him a nice clean shave. They come to Mumbai, and he wakes him up and the Sardar gives him a hundred rupees. The Sardar goes home, goes to the bathroom to wash up, he looks in the mirror and says, “That son of a bitch. I gave him a hundred rupees and he woke up the wrong guy!” (laughter)

Dr. Cashio: That was a deep sleep.

Klein: That does have philosophical import on the idea of self. This guy tells stories all the time about: How do you know what’s your real self? What’s an object of self? What is the subject of self? And stuff like that.

Catchart: Can I tell my favorite Sardar joke? The chief of detectives in Mumbai is looking to hire a new detective. Three Sardars appear to apply for the job. He says, “Look, here’s what I’m going to do. I’m going to take each of you into my office one at a time. I’m going to hold up a picture of a suspect. I’m going to hold it there for five seconds. I want you to observe everything you can about the suspect and I want you to report what you saw. He takes the first guy and shows him the picture. The guy studies it for five seconds, puts the picture down. The guy says, “Wow, this guy should be really easy to find. He only has one eye.” The chief of detectives says, “He only has one eye? This picture is a profile. Get out of here. Don’t call us, we’ll call you.” He takes the second Sardar and gives him the same task. He gives him the same picture, the guy looks at it. He says, “What did you see?” The Sardar says, “I could pick this guy out of a lineup. He only has one ear.” The guy says, “Come on. This is a profile picture. Please go away.” They ask the third guy to come in, and he looks at the picture and he goes, “Wow, it’s pretty clear this man wears contact lenses.” The chief of detectives says, “That’s interesting. I’m not sure myself whether he has contact lenses. Excuse me a second.” He goes out to his office, checks his file, comes back and says, “You’re right. This guy wears contact lenses. Tell me, how did you tell that?” The guy says, “He can’t wear regular classes, he only has one ear and one eye!” (laughter)

In the book we use that to illustrate that empiricism isn’t just sense data, it isn’t just observation. You also have to bring your interpretation in it, you have to confer with all of your other experiences and so forth. The Sardar jokes almost universally don’t do that. They play on whatever is immediately given and don’t go to the interpretive step.

Klein: The other, you asked about offending people, or making somebody the butt of your joke. Another way in which a lot of jokes do that, and I give them a pass, is that you make fun of people’s very human reactions to things. Scandinavian jokes, particularly Norwegian jokes, are very good at that. They have these two stock characters, Ole and Lena. It’s a couple and they are standard characters in all these jokes. They are both simple country people from north of…one story has Lena coming down to the nurse to report to the obituary writer that Ole passed away. The obituary writer says, “What do you want it to say?” She said, “Oh, just say Ole died.” He says, “You want it to end with that he was well-known in the community, had one of the biggest farms in the area and children and grandchildren? Anyway Lena, the first five words are free. They don’t cost you anything. Do you want to reconsider?” She said, “Ok. How about: ‘Ole died, boat for sale.’” (laughter)

Dr. Weber: That’s excellent. Unfortunately we have to take a short break but we are going to come right back after that short break with Danny Klein and Tom Cathcart. Thank you everybody for listening to Philosophy Bakes Bread with my co-host Dr. Anthony Cashio and myself, Dr. Eric Weber.

Dr. Cashio: Welcome back everybody. You’re listening to Philosophy Bakes Bread. This is Dr. Anthony Cashio and Dr. Eric Weber speaking with our fantastic gusts today, Danny Klein and Tom Cathcart. In this segment, Danny and Tom, we would love to talk to you about a more serious and heavy topics in philosophy and humor. Things like death and illness and taxes, if you’re up for that. A lot of your books, especially Heidegger and a Hippo Walk Through These Pearly Gates, kind of takes death on face-first. How does humor help us deal with serious issues? Not necessarily just facing or coping with serious issues, but looking them face on. Do you think there is something important about taking a humorous stance with these serious issues?

Cathcart: After dissing psychology a lot, I think the best answer probably comes from Freud, who thought that most jokes are based in the things that we have the most anxiety about. Most of the jokes either involve sex or death, or things having to do with sex and fidelity, and you name it, all of the things that cause anxiety. Death jokes are all over the place. Some of my favorites have to do with something… Tom and I don’t have that many years left, and so we kind of, at least I think about, “Oh is anybody going to remember me?” The answer to that one is No. (laughter)

Dr. Cashio: I beg to differ on that. I’ll remember this.

Cathcart: Hume was interesting on that question. He thought we are all just a little dot of nothing. Anyhow. What is also interesting is that there are loads of jokes like Lena and Ole jokes about how little other people care about whether they are alive or not. I’m going to tell one of my favorites. It’s a hard truth to come to grips with, that turns out to be true. The jokes help alleviate that. This guy is not feeling well so his wife brings him to the doctor and the doctor gives him a complete check-up and all kinds of scans and blood tests and everything and afterwards he says, “Mrs. Johnson I would like to talk to you alone a little bit. Your husband is actually near to death caused by stress. I have a program where we can relieve his stress, bring him right back from the brink, and live another 10 years. What you have to do is take him home immediately put him to bed. Make it as comfortable as possible—pillows everywhere. Bring him all his meals and his favorite meals to the bed and serve him there. Let him watch whatever he wants to watch on television, even if it conflict with your favorite show, let him watch. We want to keep him stress-free. If he ever gets a little sexual anxiety, do whatever you have to do to relieve him and make him happy. Just do that, a program like that for six months and I think we can bring Mr. Johnson back to life for a good long life.” On the ride home, the husband asks his wife, he says, “So what did the doctor say?” She said, “He said you’re going to die.” (laughter) I think you were asking, Anthony, whether…I heard you asking anyway, whether you thought that humor helped you stare death in the face or the unstated part of that was, is that a way of saying, “if” and trying to keep it at arm’s length so you don’t have to look at it. I think both of those things are probably true.

Dr. Weber: Here is a question for you that touches on something that we brought up in the prior segment. When you are writing this book, in terms of difficult subjects and so forth, were there topics that were really hard to tell jokes about?

Cathcart: We thought logic was going to be impossible. We thought, “How many logic jokes can there be?” It was the easiest chapter in Plato and a Platypus to write. There are a lot of jokes that turn on a logical fallacies, a lot of jokes that turn on deductive logic and errors in deductive logic. There are a lot of jokes that turn on inductive logic and what that’s all about.

Klein: A lot about confusing analytic and synthetic statements. Loads of jokes about that.

Dr. Weber: As we mentioned to you earlier, we have a segment at the end of the show called “philosophunnies”. We had one of our great colleagues on in an earlier episode, and he writes about race and about black male studies. When we were looking, we try and get a few jokes ready for the show, the kinds of things you find when you look sometimes, these horrifying, awful jokes sometimes that are incredibly mean-spirited and hurtful. Of course, we found some good things in the end that were great and reasonable to tell, anyway. Some subjects, at least for the inexperienced, seemed difficult to broach.

Klein: It seems like there are a certain amount of…I know from being Jewish, a bunch of jokes that it’s much easier for me to tell to an exclusively Jewish audience but in mixed company, it would be more difficult because it wouldn’t be reinforcing stereotypes. I just remembered when you asked that question, Eric, something with Tom that I must say, we work together so well that it’s wonderful. We had one. I don’t know if you remember this, Tom. We had one area in the Heidegger book about death where I suddenly got upset and I didn’t want to do a section about suicide, because I have become very sensitive to it because there had been a suicide in part of my family. It caused…as you can imagine, there’s nothing funny about it. Of course, there are some great suicide jokes. Of course, it’s fundamental. Suicide is fundamental to understanding Camus, for example. You can’t talk about his brand of existentialism without considering the question of suicide. Tom gave me the “in writing about death, you can’t ignore that.” He was right. I eventually got there, but at the time it was difficult for me because I could picture this relative of mine whose son had committed suicide reading it and it made me feel funny.

Dr. Cashio: So this is maybe one of those instances where humor was supposed to be more serious, because you can have a distance enough to be serious with it. That’s good.

Klein: I will tell one of my favorite suicide jokes. (laughter)

Dr. Weber: With all of that said, let’s do it!

Klein: A guy comes home and finds his wife in bed with somebody…help me with it.

Cathcart: He said, “You have totally ruined my life. I’m going to shoot myself.” They both laugh at him. He says, “Don’t laugh at me, you’re next!” (laughter)

Klein: Thanks Tom. Tom saved me again.

Dr. Cashio: Clearly you are good at using jokes to get to philosophical ideas, but do you notice anything in the structure of humor itself and the way that we approach jokes that is similar to the way philosophy approaches and understands the world? Is there a mirror…

Cathcart: It’s a classic question. Yeah. Similarity between philosophy and jokes.

Klein: We have written very eloquently about it and now it escapes me. With both good jokes, and there are a lot of bad jokes…good jokes and good philosophical questions is that they both lead you down one path and then pull the rug out from under you and set you on another path. I remember as a kid reading Hume or Bishop Berkeley and realizing, “Oh my gosh. This isn’t just the theory. All I really know about the outside world comes to me through my senses and sense data. It’s not just like you can sneak out from behind your sense data and see the thing in itself. You can’t do that. It clocked me on the head. That’s the way a really good joke just comes out of left field and just clocks you on the head.

Dr. Weber: Well I have a question for Tom because you have a book that has come out called The Trolley Problem, or, Would You Throw The Fat Guy Off of the Bridge? And, as a proverbial fat guy, what have you got against fat guys, and why are you throwing them off bridges?

Klein: Didn’t they object to the word ‘fat guy’? Your publisher?

Cathcart: Yeah. At one point the publisher was going to make him heavyset or… and then they realized that the whole history of the literature of this problem calls them the fat guy. They caved in, essentially. I have nothing against fat guys. The listeners probably know that the trolley problem has an interesting history. It appeared in the Oxford Review in 1969. Probably 30 people read it. An American fellow, who was the author of it. It was incidental to the article she was writing. An American woman philosopher whose name I’m blocking at the moment, anyway, she resurrected this in the 80’s. By this time, 300 people had read it. Then a couple interesting things happened. A bunch of psychology guys at Harvard put the trolley problem online and called it the moral sense test and asked people to weigh in on their choices about the trolley problem.

In case you may have one listener out there who hasn’t heard the trolley problem by now, after that happened, Harvard dipped its toe in the water of online learning, and for the first time out of the box, it did a traditional thing. It had a guy lecturing in the lecture hall and they put a camera on him. It seems primitive now, but that’s what they did. Because of that, it suddenly went viral. Suddenly, everybody knew about the trolley problem. The trolley problem had been around since 1969, and this guy did this in 2010 or something. Talk about how the technology changes stuff. In case you have one person out there who hasn’t heard the trolley problem, the trolley problem is that you’re standing by a trolley track and you notice a trolley barreling down the track out of control. You also see that if nothing stops the trolley, it’s going to hit five people on the track. There’s a wall on either side of them, so they can’t get off of the track, so it’s going to run right over them. You’re going, “Oh my lord, what can I do?” You look down and you notice that there’s a switch right next to you and you see that if you pull the switch you’re going to send the trolley off to a siding. Unfortunately, there’s one person standing on the siding, and so you think, “Oh boy, well. Better one than five.” The question is: Do you think that the alternative is to say, “This is out of my hands. This is out of my pay grade. I’m just going to do nothing and let fate take its course.” Or am I going to take it in my own hands and let the trolley hit the one guy instead of the five.

Most people say that they would hit the switch. The next question about the fat man is a similar scenario, but this time you’re standing on a foot bridge. You see the trolley coming out of control, and you look behind you and on the other side of the foot bridge are the five people again. They can’t get off of the track. There’s no siding, there’s no switch, there’s no nothing. You’re wondering, “What can I do? The only thing I can do is try to stop the trolley.” You need a very heavy object to throw over the bridge if you’re going to stop the trolley and you don’t see any heavy objects. And then you notice that you’re next to a fat guy. Now the question of course is: Do you throw the fat guy off of the bridge?

Klein: I say one less fat guy. (laughter)

Dr. Cashio: What do you do, Tom?

Klein: Tom’s book is fabulous because it’s all of the variations on the trolley problem and it’s funny like Tom is. But there’s one in there that I know doesn’t excite Tom as much as it does me. A distant variation of the trolley problem is the car mash-up. You know that one? Remember the one I’m talking about, Tom? Where there’s suddenly six ambulances that come into the hospital. The first guy has lost his kidney in the accident and he needs a transplant. The next guy needs the other kidney. The other guy needs a heart. You can save these five guys. The sixth guy who comes in has a little scratch on his forehead. All of his organs are intact. Do you harvest them from him to save the other five?

Cathcart: Talk abuot uncomfortable jokes.

Dr. Cashio: Is it a joke or just a…

Klein: Only if he sells his income taxes. (laughter)

Dr. Weber: We have got one more segment with our guests Daniel Klein and Tom Cathcart. We’re going to start with a question for you, Danny about one of your books. We’ll be right back everybody. Thanks for listening to Philosophy Bakes Bread. This is Eric Thomas Weber with my co-host Dr. Anthony Cashio. Thanks everybody.

[Theme Music]

Announcer: Who listens to the radio anymore? We do. WRFL Lexington.

Dr. Cashio: Welcome back everyone. This is Dr. Anthony Cashio and I’m with my co-host Dr. Eric Weber and you are listening to Philosophy Bakes Bread. Today we are talking with Danny Klein and Tom Cathcart about humor and philosophy and we’re going to do this last section. We’re going to ask some big-picture questions, maybe ask some light0hearted thoughts, and end with a pressing philosophical question for our listeners. I have a question for you, Danny. Be honest with me. In your book about travels with Epicurus, was that just so you could travel around the Aegean? “I want to go on vacation so I think I’ll write a book.”

Klein: I’m going to take the fifth on that one. This is the place where in 1967 I was footloose. Time of hippies. Whenever I would make money writing for TV, when I got a sufficient amount of money, I would travel. I ended up, through a series of accidents, on this island in the Aegean. I was going to stay for a few weeks and I ended up staying for a year. It was a very special year for me. I met people who weren’t like Harvard people. They were people who would live much more dangerous lives and would take all kinds of risks. One of my friends there had been a mercenary in Africa. Another was a British painter who had run away to sea when he was 16. These were not people you found around Harvard, and they made a big impression on me and influenced me. I kept coming back to that, even many years later. My late 30’s, I’m married, had a job, we would go back there, my wife and daughter loved it there. I had friends there and I picked up a little rudimentary Greek along the way and made some great friends and some bad friends who stayed there. My thinking about the book, Travels With Epicurus is mostly musings about what’s the best way to spend the last period of your life. I was able to shape the book. I’m very proud of that book, I should say. It’s probably the best piece of writing that I’ve done. I was able to, or tried to, at least, blend a travelogue, personal experience, and my reading of the philosophers into a seamless text. I did many drafts. I had a very good hands-on editor at Penguin, and he put me through 13 drafts of that book. When you’re older, it’s not so bad, going through 13 drafts. I enjoyed it, I must say. Steve Morrison, he was a brilliant editor. I was really happy with it when it was done. I got a good response to it.

Dr. Cashio: In thinking about Epicurus especially, I like Epicurus a lot. I’m a big fan. Was there anything where you went there to think about growing older towards the end of your life. Did Epicurus have any one big piece of advice that you would be willing to share with our listeners?

Klein: A lot of Epicurus sounds Zen-like to me. He says that if you have had the burden of ambition through much of your life, and I knew what he meant by it being a burden, he kept pointing out many different ways that it’s never enough when you have an ambition. It’s never satisfied. There’s always something better that you can achieve. Once you get old, it’s much easier to just let go of that and have a more Zen-like existence of enjoying the here and now. A lot of it, as you know, a lot of what we know about Epicurus was second-hand, except the Vatican aphorisms and the discovery in the Vatican library. They are full of those like bumper stickers. Things about growing old and letting go of ambition and the joys of talking with friends about philosophy.

Dr. Weber: I have got a question, and because this is our final segment, I have got some big-picture thoughts and questions for you. Some of what you’ve done has been to make accessible and fun some important philosophical ideas and I wonder what you feel as though your reception has been like in the academy, where sometimes people are dismissive of popular matters or the accessible is treated as though it were less-than, in terms of importance compared to the esoteric. What has been your reception among scholars in the academy?

Cathcart: We have been invited to a few places. You probably know Laura Newheart at Eastern Kentucky. The philosophy faculty all came and had a good time apparently. Had some interesting conversations with them afterwards. One of the strangest invitations we’ve ever had, it came to Danny first, was around Epicurus, actually. It was a group of biological life scientists at the University of Colorado once a year put on by a guy named Larry Gould. Larry had patented a particular biological product.

Klein: Gene mapping.

Cathcart: So the university had come into quite a bit of money. He said, he would talk about Epicurian guys, he said, “I don’t want to buy a boat. I want to do something more interesting. So he set up this program where he invites really top scientists. We heard Danny and I were there, the Nobel laureate in medicine the year before was one of the people in the audience. He got interested in Danny because of Epicurus and then through Danny, he got interested in Plato and a Platypus. We had a ball with this group. It was a little bit like your experience, Anthony, like “God, these guys are Nobel laureates. They’re dealing with mapping the genome. Here we are, two shmucks with bachelor’s degrees in philosophy making funny jokes. These guys, by the end of the day, they were so over their brains were friend from listening to each other. They were ready to laugh. It was probably the best audience that we’ve ever had. They were beside themselves. We kept getting invited back. Larry had one unbreakable rule: the same speaker couldn’t come back more than once. We were back three times. It was great. That was a big academic achievement.

Klein: We heard from some guy anecdotally, on the faculty at Harvard, that they gave our book as a prize for the best undergraduate essay in philosophy. Tom and I had a laugh because we were not Honors students. We were… To give an example in our tutorial was David Suitor. Tom was higher than I was. I was really low-end. And now, all of a sudden Harvard is giving my book as a prize? They have a thing that Tom and I…don’t tell anybody, but the other thing is we realize that the name Harvard has ganache…It sound like a Lebanese food. I’ll have the ganache with the baba- ghanoush. We realized that at some point, people take us much more seriously, the serious half, like we really know philosophy because it says Harvard after our names than if we hadn’t gone to Harvard. We don’t disabuse them of that. Don’t tell anybody though.

Dr. Cashio: We should tell our listeners, all four of us are rocking the beards today. Alright gentlemen. One of our final questions comes from the inspiration for the show. Does philosophy bake bread? Would you, Danny and Tom, say that philosophy bakes bread, or does not bake bread as the saying goes? What do you guys think? Is philosophy useful to everyday life or is it just pie-in the sky, so to speak?

Klein: I think it is. I think you said it earlier, Tom. It makes the way you think about everything, even the most trivial things, you see it in a grander framework because of the philosophical set of mind.

Cathcart: I think there is the other side of the question too. That is that a lot of philosophical discourse can get nitpicky and competitive. I read a blog almost everyday by our mentor at Harvard, the tutor that Danny was just talking about, Robert Paul Wolf, is that a name you guys know?

Dr. Weber: Absolutely.

Klein: Very nice man.

Cathcart: His blog itself is always very human and very grounded, but he has a lot of readers who are academics and they pick it apart. You know: “The Marxist take on that, what you’re saying is blah blah blah.” After a while your head hurts. I think you can obviously…cliché about academics has some truth in it too.

Klein: On the other hand, I gather around the house, and I’m not naming any names, except I only live with one person. Sometimes I’ll come out with some philosophical perspective on the dinner table subject and I’ll sometimes get that philosophy is just a painful elaboration of the obvious.

Dr. Cashio: That’s a good definition.

Klein: And I’ll say, “What makes you say that?”

Dr. Weber: Thank you so much, gentlemen. In most episodes we really feel the need to add some humor. This one perhaps needs it less, but maybe we need to celebrate it all the more. We have a segment called ‘Philosophunnies’.

Dr. Weber: Say ‘philosophunnies’

Sam: Philosophunnies!

(laughter)

Dr. Weber: Say ‘philosophunnies’

Sam: Philosophunnies!

(child’s laughter)

Klein: F’s are funny.

Dr. Weber: I wonder if you have got a final favorite joke you want to tell that we haven’t heard yet, for our segment philosophunnies.

Klein: I’ve got one. As one drifts into the end zone, or as I get to the end zone, I like absurdist humor more. I have always like absurdist philosophy. I still get a kick out of Waiting for Godot. It’s one of your favorites too, isn’t it Tommy, Waiting for Godot?

Cathcart: For sure.

Klein: So this guy, this is an old Russian joke. This guy goes to the St. Petersburg station and he goes up to another guy and says, “Don’t I know you from some place?” The other guy says, “No. You don’t know me. We’ve never met before.” The first guy says, “Just a minute. Have you ever been to Minsk?” “No I’ve never been to Minsk. I don’t know you.” The first guy says, “I’ve never been to Minsk either. Must have been two other guys.” (laughter)

Cathcart: This story illustrates the fallacy of post-hoc ergo proper-hoc. After this, therefore, because of this. For any listener out there who is unfamiliar with the ideas that just because A happened before B doesn’t necessarily mean that A caused B. A gentile man is about to marry a Jewish woman. A couple weeks before the ceremony, she comes to him and says, “Honey, I’ve got a big favor I need to ask you. This is big, but I want you to think about it. It would be very important to my mother if you were to convert to Judaism. The guy says, “Well, let me think about that. Yeah, if it’s that important to you and your mom, I’ll convert to Judaism. Just tell me what’s involved. She says, “Well, first of all you would have to be circumcised. He goes, “Circumcised? Geez. At my age? It sounds like it might be terribly painful.” She says, “I have no way of knowing that.” He calls up a Jewish male friend of his. He says, “Look, I’m converting to Judaism, I have to get circumcised. I’m really kind of worried about it. Is it painful?” The guy says, “Well, to tell you the truth, when I had it done I was eight days old, so I don’t remember it as painful. But I’ll tell you this. I couldn’t walk for a year afterwards. (laughter) That’s the post-hoc ergo proper-hoc.

Dr. Weber: That’s classic. Well Anthony and I of course always try to prepare and grab some jokes so we strung together a bunch of our favorites, but we’ll just each tell you one from your books that we’ve got listed here. Anthony you want to tell one?

Dr. Cashio: I like this one a lot. After 12 years of therapy, my psychiatrist says something that brought tears to my eyes. He said, “No habla Ingles.” (laughter) I think that’s my favorite joke ever.

Cathcart: I’ve forgotten what that joke proves.

Dr. Weber: I’ll have to figure it out and put it in the show notes. This one is a great one, speaking of Freud. What is a Freudian slip? It’s when you say one thing but you mean your mother. (laughter)

Dr. Cashio: I have got to tell one more. I like this one. A snail was mugged by two turtles. The policeman asked him what happened. The snail said, “I don’t know. It all happened so fast.”

(laughter, rimshot)

Dr. Weber: Thank you so much, gentlemen.

Dr. Cashio: Last but not least, we do like to take advantage of the fact that we today have very powerful social media that allow for two-way communications even for programs like radio shows. We want to invite listeners to send us their thoughts about big questions that we raise on the show.

Dr. Weber: Given that, we would love to hear your thoughts, Danny and Tom, whether or not you have a big question that you want us to raise for our listeners?

Cathcart: I have one from Heidegger. That is: Why are there things that are rather than nothing. (laughter) Do you remember that one from Sein und Zeit? I remember laughing so hard when I read that that I never progressed to page two.

Klein: You guys are too young to remember the Jack Benny radio show. Do you remember radio? Part of Benny’s personality, his character on the show was that he was a skinflint. He gets mugged by a guy and the guy says, “Your money or your life.” There’s no reply, so he says, “Your money or your life!” and Jack Benny says, “I’m thinking. I’m thinking.” (laughter)

Dr. Cashio: I want to thank everyone for listening to this episode of Philosophy Bakes Bread, food for thought about life and leadership. Your hosts today have been dr. Anthony Cashio and Dr. Eric Weber and we have been really grateful to be joined by Danny Klein and Tom Cathcart. I want to give a personal thanks to you guys. I started teaching philosophy several years ago. After my first intro to philosophy class I was like, “Something is wrong here. Something is not quite working.” My mother-in-law gave me a gift for Christmas, and it was your books! I read them and it changed the way i do my intro class and it inspired my teaching my style.

Klein: That’s thrilling to hear.

Cathcart: We have heard from a couple people in academia, that because their students come with a fear of philosophy, that they ask them over the summer to read Plato and a Platypus, and they say this isn’t really as horrible as you think. Lighten up and read this.

Dr. Cashio: Sometimes I’ll open up my class, even if it is a logic class, with just the dumbest joke I can find. You go from there to talking about it.

Klein: That’s so gratifying.

Dr. Cashio: That’s been fairly successful, at least for me. I want to personally thank you for that. Back to our listeners. We hope our listeners will consider sending us your thoughts on anything that you’ve heard today that you would like to hear about in the future, or about the specific question that we’ve raised for you. It’s a doozy of a question. Why is there something rather than nothing? I don’t know if I can do that whole Heidegger part.

Klein: In the English translation, it’s why are there Essence rather than nothing. I don’t even get that.

Dr. Weber: Once again, you can reach us in a number of ways. We’re on twitter @PhilosophyBB, which surprisingly stands for Philosophy Bakes Bread. We’re also on Facebook at Philosophy Bakes Bread, and check out our SOPHIA’s Facebook page while you’re there, at Philosophers in America.

Dr. Cashio: You can of course, email us at philosophybakesbread@gmail.com, and you can also call us and leave a short recorded message with a question or a comment that we may be able to play on the show, reach us at 859-257-1849. That’s 859-257-1849. Join us again next time on Philosophy Bakes Bread: food for thought about life and leadership.

[Outro music]