This fortieth episode of the Philosophy Bakes Bread radio show and podcast features an interview with Dr. Larry A. Hickman, former Director of the Center for Dewey Studies at Southern Illinois University, talking with co-hosts Eric Weber and Anthony Cashio about John Dewey’s rich ideas about democracy and education, as well as what we can say about the state of each today.

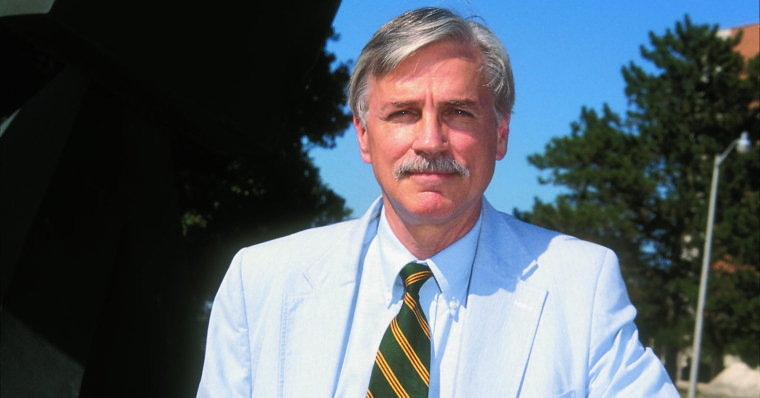

Dr. Hickman is a prolific scholar, who has written on countless social issues from gay rights to school funding. He and his colleague Dr. Tom Alexander co-edited a two-volume set of some of the greatest resources available for studying Dewey’s philosophy, The Essential Dewey, Volumes 1 and 2. Larry also directed the Center for Dewey Studies for many years, obtaining grant after grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities and creating an incredible set of digital resources collecting and digitizing Dewey’s works and the works of his contemporaries. In this episode, Larry presents some sobering concerns about the state of education in the United States today, as well as what that and other problems mean for democracy here.

Listen for our “You Tell Me!” questions and for some jokes in one of our concluding segments, called “Philosophunnies.” Reach out to us on Facebook @PhilosophyBakesBread and on Twitter @PhilosophyBB; email us at philosophybakesbread@gmail.com; or call and record a voicemail that we play on the show, at 859.257.1849. Philosophy Bakes Bread is a production of the Society of Philosophers in America (SOPHIA). Check us out online at PhilosophyBakesBread.com and check out SOPHIA at PhilosophersInAmerica.com.

(61 mins)

Click here for a list of all the episodes of Philosophy Bakes Bread.

Subscribe to the podcast!

We’re on iTunes and Google Play, and we’ve got a regular RSS feed too!

Notes

- John Dewey’s New York Times obituary.

- John Dewey, Democracy and Education (New York: The Free Press, 1916/1997).

- G. W. F. Hegel, The Phenomenology of Spirit (New York: Oxford University Press, 1977).

- Zachary Crockett, “The Case for More Traffic Roundabouts,” Priceonomics (September 18, 2015).

- Laurie Roberts, “Roberts: Am I Shocked by Senate President’s (continued) Self Dealing? Yep. And Nope.” The (AZ) Republic & The USA Today, March 6, 2017.

- Charles Murray, The Bell Curve (New York: The Free Press, 1996), the book that Larry argues we should have stopped paying attention to 20 years ago.

- SOPHIA won the American Philosophical Association / Philosophy Documentation Center Prize for Excellence and Innovation in Philosophy Programs!

You Tell Me!

For our future “You Tell Me!” segments, Larry proposed the following question in this episode, for which we invite your feedback:

“I’ve got an answer to this question [in a breadcrumb coming soon], but I want to know yours:

‘What is the meaning of life?’”

Let us know what you think matters! Twitter, Facebook, Email, or by commenting here below.

Transcript

Transcribed by Jennifer T. of Rev.com, June 22, 2018.

For those interested, here’s how to cite this transcript or episode for academic or professional purposes (for pagination, see the printable, Adobe PDF version of the transcript):

Weber, Eric Thomas, Anthony Cashio, and Larry A. Hickman, “Democracy and Education Today,” Philosophy Bakes Bread, Episode 43, Transcribed by Matthew K. of Rev.com, WRFL Lexington 88.1 FM, Lexington, KY, August 28, 2017.

Radio announcer: This podcast is brought to you by WRFL, Radio Free Lexington. Find us online at WRFL.FM. Catch us on your FM radio while you’re in central Kentucky at 88.1 FM all the way to the left. Thank you for listening, and please be sure to subscribe.

Weber: Hey, everybody. You’re listening to WRFL Lexington 88.1 FM. This is Eric Weber here to play you Philosophy Bakes Bread.

Weber: I have one small disclosure to make, which is that there were a few little artifacts that we could not figure out after a lot of time and effort how to totally get rid of in the recording of Dr. Hickman’s audio, but we have cleaned it up as best we can, and I think pretty quickly you don’t really even notice it anymore. But at the same time, I want people to know that we know that, and we appreciate your patience with us. That said, I don’t think many people will notice much of anything, honestly.

Weber: So, I hope you’ll enjoy this episode number 40 with Dr. Larry Hickman in which we’re going to be talking about democracy and education in America today. Here, without further ado, is episode 40 of the show.

Cashio: Hello and welcome to Philosophy Bakes Bread. Food for thought about life and leadership.

Weber: A production of the Society of Philosophers in America, aka SOPHIA. I’m Dr. Eric Thomas Weber.

Cashio: And I’m Dr. Anthony Cashio. A famous phrase says that philosophy bakes no bread, that it’s not practical, but we in SOPHIA and on this show, aim to correct that misperception.

Weber: Philosophy Bakes Bread airs on WRFL Lexington 88.1 FM, and is distributed as a podcast next. Listeners can find us online at PhilosophyBakesBread.com, and we hope you’ll reach out to us on Twitter @philosophybb, on Facebook @PhilosophyBakesBread, or by email at PhilosophyBakesBread@gmail.com.

Cashio: Last but not least, you can leave us a short, recorded message with a question or a comment or bountiful, bountiful praise that we may be able to play on the show at 859-257-1849. That’s 859-257-1849.

Cashio: On today’s show, we’re very excited to be joined by Dr. Larry Hickman. How are you doing today, Larry?

Hickman: Great. Good to be here.

Cashio: We are very excited to have you on. Dr. Hickman is an emeritus professor of philosophy at Southern Illinois University Carbondale, and the former director or the Center for Dewey Studies. That’s the American philosopher John Dewey, who we’ll definitely be talking about a little bit later in the program. Larry is also the author of numerous articles and books including the edited collection of essays that he completed with his colleague Tom Alexander, that is the Essential Dewey, two volumes. Volumes one and two. It’s some of the best resources for learning and understanding John Dewey’s work, at least in our opinion.

Weber: That’s right. That’s right. Larry’s other influential books include John Dewey’s Pragmatic Technology, Philosophical Tools for a Technological Culture, and more recently, Pragmatism as Post-Postmodernism. In addition to his own writing, Larry has led a team of scholars and editors who have edited an enormous number of documents and resources for studying John Dewey’s work having secured extraordinary support from the National Endowment for the Humanities over and over again, and supporting the work of the center. We have incredible tools for studying and applying John Dewey’s insights today in large part because of Larry’s leadership.

Cashio: Larry is also a cofounder of the American Institute for Philosophical and Cultural Thought, with previous guests on this show Randal Auxier and John Shook. Today we’re going to talk with Larry about John Dewey’s theories of democracy and education, and what they can teach us about the state of democratic education today. Does that sound good, Larry?

Hickman: That sounds good. I can’t wait to get started.

Cashio: Let’s get into it.

Weber: Excellent. There’s a line from President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Larry, and he said that democracy cannot succeed unless those who express their choice are prepared to choose wisely. The real safeguard of democracy therefore is education, he said.

Weber: We’re glad to have you on, and this first segment is called Know Thyself. We want to begin, before we get into democracy in education and so forth, Larry, we want to ask you whether you know thyself, and to tell us about yourself. We have a few other questions for you after that.

Hickman: Thanks, and again, it’s great to be here. Knowing thyself, of course that goes back to the Athenian Greeks, although I’m sure there were people who were working on that problem of knowing themselves long before it got articulated in that way. But knowing thyself is really a lifelong project seen from the standpoint of education. Because education involves growth, and if you stop growing, then you’re dead. So, knowing thyself is an extremely important project.

Weber: Yes.

Hickman: The other side of that is knowing thyself is a matter of knowing your place in a culture, knowing your culture, knowing your history, a having pretty good ideas about what might be around the corner. Knowing thyself, again, is a great, long project that all of us should be involved in at all times.

Cashio: Well, that’s good, Larry, but tell us about yourself. How well do you know yourself? I think you’ve avoided the question. Maybe you could tell us [crosstalk 00:05:43] about your education since I think you’re right: education is not about dying.

Hickman: I suppose [crosstalk 00:05:47] some of my students might have said that in my logic classes, but it’s not true.

Hickman: My background is in, undergraduate degree is in psychology and in religion. Graduate degree of course is in philosophy. I went to the University of Texas in the 1960s to study philosophy, and what I found was … The first thing I found was very, very cheap tuition, $50 a semester plus some minor fees. I am serious.

Cashio: Are you serious?

Hickman: And things going to lead me to say-

Cashio: That’s amazing.

Hickman: … quite a bit about funding for state higher education, which has deteriorated badly over the years, but I’m going to get back to that. But University of Texas was chartered to provide a university of education of the highest quality. Texas took it very seriously in those days, so I was really blessed to find a philosophy department that was pluralistic in the sense that courses were offered all the way from the pre-Socratics, that is those philosophers who were before Plato and Aristotle, right up to the present. Some major figures in the history of philosophy were represented. It was a big department of some 30 individuals, and it was a terrific experience. I was like a kid in a candy shop.

Hickman: I went on from there to write a dissertation in the field of the history of logic. Even though I hadn’t planned to go into the field of the history of logic, especially late scholastic logic, the scholastic logic of the 16th century, I regarded it as a kind of intern’s position in scholarship tools, research and scholarship tools. Along the way, it did solve a problem that had been bothering me about one of the aspects of the work of one of the great pragmatist philosopher Charles Peirce.

Hickman: But I think one of the reasons that I continued in philosophy and really found that it was a home for me for my profession, is that philosophy is basically, at least in my view, is a critique of culture. It’s a way of looking at those kinds of things in our culture that work, and trying to find ways that they can be supported, but also finding those things that don’t work, and trying to reconstruct those and then build on them.

Hickman: This is basically John Dewey’s idea about education. I’ll say something about John Dewey a little later, but this really is what kept me interested in philosophy. The flexibility. I could go in many different directions. Consequently, I have written articles on gay rights issues, on film theory and criticism, on ethics, on logic, on environmental studies, and even the philosophy of religion. All of this under the umbrella of philosophy.

Cashio: Philosophy as a critique of culture, I like that. We haven’t heard that one yet, have we, Eric?

Weber: Right.

Cashio: That’s good.

Weber: No, we haven’t. No, we haven’t. Larry, now, you mentioned a term that some of our listeners may not be aware of, and it was scholastic logic. What is scholastic logic?

Cashio: And keep it short.

Hickman: Yes. Good question. Good question. The short answer, right? Well, it’s basically the world view of the Middle Ages. The critical and logical underpinnings of the worldview of the Middle Ages from approximately the 9th to the 16th or 17th century. And of course, there are still scholastic logicians and scholastic philosophers around, but these would’ve been people who were building on the work of Thomas Aquinas, William of Ockham, and others, and John Duns Scotus. These were very important, central figures in the history of medieval philosophy.

Weber: Very nice.

Cashio: I like it.

Weber: I happen to know something, a little bit about you, Larry. Larry, everybody, I should disclose, was my dissertation director. I was very fortunate for that to be the case, but I do remember in your story something about religion in your background, and that perhaps you didn’t originally have plans to go forward in philosophy. Am I right about that? And if so, what were your original plans? What were you thinking of?

Hickman: Well, my undergraduate degree is from Hardin–Simmons University, and that’s a very good liberal arts college university in Abilene, Texas. That’s west, far west, of Dallas and Fort Worth almost into the point you get to the panhandle. I received a very good liberal arts college education there, and there was a good program in music and in the arts, but there were only 12 hours of philosophy offered. So that just kind of whetted my appetite.

Hickman: My major was in psychology, my minor was in religion, and I was planning to be a Baptist minister. Rather than go to seminary, I decided that I would take a year off and study philosophy. Some of my friends said, “Oh no. If you do that you’ll just keep going,” and I said, “Well, if it happens, it happens.” That’s-

Cashio: That’s often the case, though.

Hickman: Well, Austin was quite a draw, too. Austin in those days was quite a wonderful place, and still is, I’m sure.

Weber: And they were worried about you following that path?

Hickman: Yes. They thought probably I would get into these big questions, these big issues, that transcended theological issues, and in fact that turned out to be the case. I got interested in the big ideas that drive our culture and our civilization. The study of Darwin, Einstein, Freud, Copernicus. I got interested in the tools that we use to examine and receive knowledge and values. For instance, Plato’s examination of the nature of abstractions, Aristotle’s notion of the golden mean, Hegel’s development of the idea of thesis, antithesis, synthesis, and I got interested more generally in where culture’s headed, with it’s been, and how we can make corrections.

Hickman: I would give as an example of that John Dewey’s naturalistic ethics, which I think really supplant some of the non-naturalistic ethics that had been propounded by exclusivist, supernaturalist religions, and also by some non-naturalistic philosophers. Perhaps a better example if Descartes’ split of body and mind. What’s right about that, and what’s wrong about that, and where does that take us?

Hickman: The philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein, that’s kind of hard to say, called this getting the fly out of the fly bottle. That is, going back into the history of philosophy and saying, “Okay, these guys were good. They addressed the questions that they had at the time, but are those questions still relevant for us? Are their answers still relevant for us?”

Weber: There were a number of terms that people may not recognize. One of them was Hegel and thesis, antithesis, synthesis.

Cashio: Okay.

Hickman: Yeah. I probably shouldn’t have brought that up.

Weber: Can we get a nutshell, you know, because I think a lot of the other things, I think people have heard of the golden mean, right?

Hickman: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Weber: Which is that the moderation is what’s right between extremes between brashness and cowardice. You want to be courageous; that’s the moderation, right? Well, when it comes thesis, antithesis, synthesis, a casual listener may wonder, “What on earth is that about?” Have we got maybe a 30-second or a one-minute “here’s what that’s about”?

Hickman: Sure. Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit runs to about 500 pages. I can boil that down to 30 seconds.

Weber: Perfect, perfect.

Hickman: The idea is that ideas as well as movement, cultural and political movements for example, have in themselves the seeds of their opposites. At a certain point, those ideas, those cultural movements, tend to break down and generate their opposites, and then there’s a struggle between the original idea and the opposite. What comes out of that, in many cases, is a third position.

Hickman: John Dewey, who was a genius, has taken this approach, that is he would take the extreme positions he found among his colleagues, and in the history of philosophy. He would sift out what was good about those extreme positions, and he would build a third position that took out the chaff, saved the wheat, and built a new and better position. So that’s basically the idea in back of Hegel’s thesis, antithesis, synthesis.

Cashio: Fantastic.

Weber: Very nice.

Cashio: Yeah. Well, Larry, we always ask two other questions in this first segment. You’ve already actually answered one of them. We always ask “What is philosophy?” and you gave us that wonderful answer about philosophy as a critique of culture.

Hickman: Oh, I’ve got more to say about that.

Cashio: Oh, all right. Well, go for it, then.

Hickman: Well, there have been some interesting definitions of philosophy along the way. The German philosopher Martin Heidegger thought of philosophy as a kind of heroic demolition of the past and a fresh start in terms of his own way of doing things. University of Chicago philosopher Martha Nussbaum has thought of philosophy as a kind of a salvaging operation where we take the building blocks that were used to build classical, Athenian, and Greek philosophy, and Roman philosophy, and we reconstruct those into new edifices.

Hickman: The German philosopher Jürgen Habermas has said, “Well, philosophy is either” what he calls [foreign language 00:14:51] or [foreign language 00:14:52]. That is, a placeholder or a place finder that is holding the places from the very beginning of those things that would emerge from philosophy, for instance, psychology, and either that, or finding the places for the various disciplines that have emerged out of it.

Hickman: For Dewey, it’s different. For Dewey, philosophy is a kind of a liaison officer. It is able through one its major functions, the study of inquiry, to allow conversations between disciplines that normally do not talk well to each other. A good example of that would be the philosophical work that’s going on in cognitive neuroscience today.

Weber: Very nice. Very nice answer, and very nice explanation. I want to make sure we ask you a little bit about an example of some of what we’ve been hearing, but we’re going to do that right when we come back with Philosophy Bakes Bread after a short break. This is Eric Weber. My cohost is Anthony Cashio, and we’re very fortunately talking with the great Larry Hickman. Thanks everybody for listening. We’ll be right back.

Cashio: Welcome back everyone to Philosophy Bakes Bread. This is Anthony Cashio and Eric Weber here talking today with the great Larry Hickman about democracy, about education, and about how both of these play out in American culture today. So, in this second segment, we’re going to talk with Larry about what he has learned about democracy and education through his studying of the philosopher John Dewey. In the next segment, we’ll discuss in greater detail the sort of state of education today in America both in kindergarten through high school levels and in higher education.

Cashio: So, Larry, let’s get to it. A lot of your prolific work, and it is prolific if you look up his bibliography, right? A lot of your prolific work has focused on teaching and expanding on the thought of John Dewey. You are the head of the Dewey Center. So, a lot of our listeners are probably not aware of who Dewey was, and why he remains so important today. Maybe you could give us a quick introduction, and I’ll go ahead and ask the most important question you probably get all the time: isn’t Dewey the guy who invented the Dewey Decimal System?

Hickman: Short answer, no.

Cashio: No.

Hickman: I do get asked that question a lot. He was also not the guy who ran for our president in 1948. That is, he wasn’t the guy who sailed into Manila harbor either. Those were other Deweys.

Hickman: But John Dewey was born in 1859, died in 1952 at the age of 92 years old. That means he was born in an age of wind and water and wood technology, and he died the year of the testing, the mass marketing of the birth control pill and the explosion of the hydrogen bomb. He lived through several world wars, and had a remarkable career. On the occasion of his 80th birthday, the New York Times hailed him as America’s philosopher. There was another-

Cashio: Wow.

Hickman: … public intellectual who said that Americans really didn’t know what to think until Dewey had spoken.

Hickman: So, he was one of the great public intellectuals of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He was involved in ethics and logic, in philosophy and religion, perhaps most famously in education. He had an appointment in his later years both in the philosophy department at Columbia University and also at Teachers College at Columbia University. He was one of the major reformers of American education, and helped move K-12 education from rote memory into something similar to what we see today when education is at its best.

Hickman: One of the great stories about Dewey when he was working to establish his Laboratory School at the University of Chicago in the 1890s, he was going around looking for furniture for his school, and all he found were these desks in rows that bolted down to the floor. Finally, he described to one salesman what he wanted, and the salesperson said, “Oh, I see. You don’t want a bit of furniture. You want a bit of furniture for learning.”

Hickman: So he got tables that his students could sit around, leave, interact, do the various kinds of things that would help them develop certain kinds of skills: listening to one another, creative interaction in ways that would be influential in their thinking about democratic life and the way that we live together, communication skills. And you don’t get that when you are asked to just repeat back information that’s been given to you. And by the way, that brings up the matter of No Child Left Behind, Common Core, and Race to the Top that I’ll get to in a moment.

Hickman: But Dewey was a remarkable figure, active in many areas, influential in philosophy and especially in education.

Weber: Well, Larry, in the first segment, we heard a little bit about Hegel, and you explained that Dewey applied some points from Hegel about thesis, antithesis, synthesis. This idea of there being one idea that kind of has its opposite implied, and then brought up, and then out of the conflict between the two comes some synthesis, some third thing. What is an example where Dewey usefully applied that kind of insight from Hegel?

Hickman: Yeah. One of the areas where he applied it was in the field of ethics. There are still people who think about ethics and the norms of ethics as being given to us from external sources. That is, external to human experience. This would be revealed religions, this would be various types of non-naturalistic ethics. They think these ideas are pretty much set in stone as, for instance, the story of the 10 commandments, and that there are no exceptions. That is, they are just there.

Hickman: Other people think that the norms of ethics, and there are fewer of these, but there seem to be more every day, that the norms of ethics are just arbitrary. That is, you can either pay attention to them or not, and the only danger is if you get caught. I could mention some names in the current political arena right now, but I won’t go into that.

Hickman: Those are two extremes. In the middle, Dewey thought, was a third position. He wanted to take the best of both positions, the best of the former position. That is, the revealed or external idea about ethics, the non-naturalistic ethics, is that there are ideas that have come to us through our culture that we need to take very seriously. So that’s what’s good about that. What’s bad about that is that it puts the study of ethics outside of human activity, and it says that these ideas are already accomplished and finished and fixed.

Hickman: On the other extreme, there is the kind of anarchical approach, or arbitrary approach, or total relativist approach which says that everything is up for grabs at all times. What’s good about that is that it inspires a kind of experimentalism. What’s bad about it is that it does not take into account the marvelous attainments in the field of the study of ethics and morals.

Hickman: So what Dewey did is he tried to find a position that took the good from the extremes and jettisoned the bad. He came up with the idea that ethics is a naturalistic kind of enterprise, and in fact, it’s very similar in ways, and this is my own metaphor, very similar to the genesis of norms in vehicular traffic. For instance, there are conventions based on long held customs. For instance, what side of the road you drive on. That’s no problem. You can just choose that. That’s arbitrary, but once it’s arbitrary, you need to observe it.

Hickman: Two, there’s research into what has led to maximizing safe practices through institution of standards pertaining to right of way, for example. Especially as they pertain to new types of traffic interchanges so that you don’t have to completely have somebody out there standing and directing traffic at all time. These roundabouts or traffic circles would be a good example of that.

Weber: Nice.

Hickman: Third, there’s agreement about procedures and enforcement that go beyond what’s merely local, but it’s not far as to evolve claims of universality in the sense that the norms are universal. But they are universalizable. That is, for instance, policing practices of vehicular traffic are the object of study and improvement over time.

Hickman: Then fourth and finally, there’s research into better ways to delegate certain tasks and so on. These are some of the ideas that underpin a naturalistic ethics that involves criticism of cultural values and experimentation into ways in which they can be improved.

Weber: Nice. I really like the example of traffic patterns because in a sense it is arbitrary whether we all drive on the left or the right, but once that’s picked, you don’t want to be driving on the left in the United States anymore.

Hickman: Right. Exactly.

Cashio: There’s a town right down the road from me where they just put in a traffic circle, and it’s probably the first traffic circle in the county, and everyone is losing their minds there. They don’t know how to drive around it, they don’t know what’s going on. I’m sure they’ll get it pretty quickly. They put it like right in front of a big high school, and I think everyone’s like, “Oh my god. There’s going to be accidents.”

Cashio: Hopefully they’ll get used to it, but I think it’s an example of the norms, right? It’s something that’s normal. I mean, if you go to Europe it’s all over the place. Very easy to drive, but everyone’s used to their stoplights, and so you introduce a traffic circle and …

Hickman: Well, this is a very good example of one of the points I made. That is, one of the ways that ethical norms get generated is by looking at what other people have done successfully. To the best of my knowledge at this point, this emerging number, this growing number of traffic circles is based on studies that have been done in Europe. We’re seeing more and more of those. I spent a little time in St. Louis, and I’ve noticed an increasing number of traffic circles there as well.

Weber: Very interesting.

Cashio: There you go.

Hickman: So anyway, that’s the idea. You jettison what is bad from the extremes, and you pick up what’s good, and you try to put that together and improve on it.

Hickman: One of the examples that’s been mentioned recently was the idea of the kind of communism that flourished during the Soviet era on one extreme, and then the kind of extreme libertarianism bordering on anarchy that exists on the extreme concern. Somewhere in between there, you’re going to find a political middle. For some people, that might be a kind of a social democracy slightly left of center. For some it might be a more laissez-faire capitalism slightly to the right of center.

Hickman: But there’s no reason why those people slightly to the left and slightly to the right can’t come together to talk about ways to improve the total situation, although that seems to not be the case at this point.

Weber: Right. They’ve been more able to do it in the past.

Hickman: Right.

Cashio: Right, right. You know, you brought up the idea of democracy, and I know this is another major idea for John Dewey. I was kind of thinking about the relationship between democracy and education, because that’s of course Dewey’s major work.

Cashio: There’s a common phrase that we hear maybe at the dinner table or in the classrooms. We like to say something like, “This is not a democracy.” Which is to say there’s a sort of a sense that someone’s the boss in a lot of context, and people think that that’s the best way. I know if I let my kids vote on what they get to eat for dinner, it would be ice cream every night, right? Maybe [inaudible 00:26:27]. What is democracy in the broad sense, and is it always a good thing? Should little Timmy get a vote on whether or not he has a bedtime?

Hickman: Little Timmy is probably an anarchist, not a democrat.

Cashio: Ah. Blew the whole thing up.

Hickman: Well, the point is, we need to listen to people, and we need to listen to even those people who are outside our [inaudible 00:26:50], our bubble. But at the same time, Dewey was very clear about this in terms of education, you don’t want to let kids run wild. In fact, this is another example of the kind of way that he built his educational ideas.

Hickman: The idea of rote memory is at one extreme. You give the information, like on the teaching to the test. You put that information out there, and then you get it back. Of course, what that means in the current situation is that you’re spending more time teaching to the test, less time on such academic areas as the arts, civics, and even physical education because that time has to be spent on teaching to the test. On the other side, you have some of Dewey’s followers in the 1930s who thought that if you just turned kids loose, they would find their own way. So you brought them to school, and you were going to see what they did.

Hickman: Dewey repudiated both of those positions including those people who claimed his own disciples. He thought that teachers are there for a reason. They need to be the coaches. Not an authority figure, but coaches that allow the kids to develop themselves in a guided way through their educational experience. That’s really a problem in terms of current education in K-12 at this point.

Weber: Well, Larry, we’re going to come back to the subject of education and our current state of affairs in the next segment, but before we get there, note that there have been a number of people, including President Carter, but not only, who have said that the United States is not a democracy, that it’s an oligarchy. So, a country ruled by the few and rich, right? Are they wrong? [crosstalk 00:28:28] Is the United States a democracy?

Hickman: [crosstalk 00:28:28] It has at times been an aspiring democracy. Right now, I would say that it is a threatened democracy.

Weber: Very interesting. Well, we’re going to come back after a short break. Talking with Larry Hickman, this is Eric Weber with my cohost Anthony Cashio. Thank you, everyone, for listening to Philosophy Bakes Bread. We’ll be right back.

Radio announcer: If you’re hearing this, that means podcast advertising works. WRFL is now accepting new applications for advertising in a selection of our original podcast series. If you or someone you know owns a business in central Kentucky and would be interested in advertising on WRFL’s original podcasts, please email development@wrfl.fm.

Cashio: Welcome back to Philosophy Bakes Bread. This is Anthony Cashio and Eric Weber, and it is our tremendous pleasure this afternoon to be talking with Larry Hickman about the relationship between democracy and education. In this segment, last segment we talked about the philosophy of John Dewey and how it helped inform theories about democracy and education in general, but in this segment we’re going to talk more specifically about contemporary education as particularly at K-12, K through I guess graduate school, right? Education just in general. I guess, Larry, my question is what should a democratic approach to education look like?

Hickman: Yeah. That’s a very important question, and it’s a question which is really crucial for the future of our democracy. If Dewey were here today, and I hesitate to put words in the mouth of a person who’s been gone for over half a century, but if Dewey were here today, I think it’s very safe to say that he would not be pleased with the direction of education in America.

Hickman: For one thing, there has been an assault on not only K-12, but higher education from a number of sources. For profit higher education is one example. The University of Phoenix is one sad example where you had more-

Cashio: Wow.

Hickman: … of their staff involved with recruiting than in actual teaching. And by the way, these people are getting money from the taxpayer because a lot of the money they get from-

Cashio: Oh, wow.

Hickman: … is from students-

Cashio: Pell grants.

Hickman: … for student scholarships, the GI Bill and so on.

Hickman: The second thing, and just the for-profits, but also the for-profits that are owned by nonprofits. A good example of that would be Liberty University in Virginia, which last year pulled in about $330 million in federal funds from the government at a point where the University of Virginia pulled in $35 million from the federal government in terms of student support. So that’s a ratio of more or less 10 to one. So here you have a nonprofit that owns for-profit. The same has been the case elsewhere, and of course Liberty University is a religious university. It pushes a very clear ideology, and in fact I would argue that there are serious first amendment issues here in terms of state support for religious doctrines.

Hickman: There are also legislative scams such as the one in Arizona where the president of the senate got a bill passed that if you donated to a student tuition organization, that you could take that right off your taxes. Not off your income, but off your taxes.

Weber: Wow.

Cashio: Wow indeed.

Hickman: Yeah. These student tuition organizations were mandated to only take 10% overhead, so if in the case of his student tuition organization, they got $18 million, he raked in $1.8 million. Well, it didn’t stop there because he paid himself a salary from that student tuition organization working 40 hours a week of course in addition to being the president of the state senate. And in addition, he hired a firm, which he owned, to do the bookkeeping, and in fact the bookkeeper worked in a building which he owned and charged him rent, and he got a free car. This is the kind of scams that are being perpetrated on the taxpayer, and it is symptomatic of the way that K-12 and higher education funds are being diverted from public education into private pockets.

Hickman: Another example of the threats to democratic institution involves ideological threats. There are current legislators in Missouri and Iowa who want to abolish tenure. I can tell you as one who is very outspoken in supporting gay rights at Texas A&M University in the 1980s, a situation that we took all the way to the US Supreme Court to get recognition for gay students at Texas A&M, if I hadn’t had tenure, I would’ve been out. Let’s see, I was going to say out on my whatever, but I would’ve been expelled from the … I would’ve been gone. I would’ve been gone. Actually, I’ve heard that from someone who was inside the Republican establishment at that point, that my name came up in a conversation in the governor’s office.

Cashio: Oh, wow.

Weber: Wow.

Hickman: So, there are legislators that want to get rid of tenure. And in fact, there was even one case, let me see if I can find the report here, where a legislator actually proposed … Yeah. Here’s an Iowa bill by someone named Senator Mark Chelgren. Here I’ve got a picture of him smiling, smiling, smiling because he wants there to be a voter registration data provided for every perspective instructor, and not make any hire which would cause either Democrats or Republicans on an institution faculty to outnumber each other by more than 10%.

Cashio: Oh, I remember that. I remember him for that proposal where he wanted a perfect [crosstalk 00:34:42] balance between Democrats and Republicans.

Hickman: So, there’s another threat. And of course, there’s always the threat of those legislators who want to get rid of those “non-practical courses.” And that would of course include philosophy in their view.

Hickman: On a broader scale, there are efforts in the United Kingdom and United States to change the way that higher education works. Among other things, the Texas seven solutions proposal would increase class sizes. As someone who’s taught classes of 250 at Texas A&M, I can tell you you don’t have the time. No human being has the time to give the attention to 250 students during a semester.

Hickman: Want to increase class sizes. They want to redefine how professors are remunerated, how their salaries are calculated to take into account external funding. Research would be defined as external funding. Well, there’s a problem with that because there’s not much external funding in the humanities. So, humanities professors are going to take it on the chin as will people in the arts.

Hickman: They also want to establish a bell curve of mandated grade distributions. My question is what is that going to do to honors classes? Because everybody in an honors class expects to get an A, and in most cases they deserve A’s. I taught honors courses at Texas A&M University-

Cashio: Yeah, they earn it. [crosstalk 00:36:10].

Hickman: … and those students deserved A’s. This would make a serious problem in that regard.

Hickman: So, there are many assaults. Let me just mention one that has to do with K-12.

Weber: Right.

Hickman: Estimates go anywhere from $1 to $8 billion a year spent by organizations that furnish testing materials. These have great armies of lobbyists, and what they do is they convince legislators there should be more testing. I think it goes without saying that some of that money winds up in campaign coffers. If we’re spending that kind of money on testing, what could we be doing in terms of increasing the salaries of teachers, increasing the number of teachers, and decreasing class sizes with all that money?

Hickman: I’ll mention one more problem, and that is charter schools. Now charter schools, I don’t want to condemn charter schools in general because some of them are very good, but there is an enormous possibility of problems with charter schools. Cherry-picking. That is, charter schools get to pick which students. This raises the possibility of racial segregation, for instance.

Hickman: There are first amendment issues that have to do with religious instruction, and in fact the new secretary of education, Betsy DeVos, has argued that, on a couple of grounds, that there should be no oversight of charter schools. They should be able to do what they want, and that there should be a massive transfer of funds away from public education into charter schools, some of which are public education, but some of which are not.

Cashio: No oversight whatsoever?

Hickman: No over … She was asked several times in her-

Weber: Wow.

Hickman: … senate hearing to commit herself to oversight, and she avoided the question at each time. She has said-

Weber: Wow.

Hickman: … in print that it is part of her task to increase the glory of god’s kingdom in the educational sphere. So, you can see what she’s doing there.

Hickman: We have no indication in any of this, we have no indication in any of this of the ideas that Dewey held very, very firmly, and of great importance. That is that K-12 and higher education, those should be places where students learn who they are, learn about their culture, experiment, find ways of experimenting with their future selves. There is nothing of that in any of these assaults on K-12 or higher education that I’ve mentioned.

Hickman: I should also say that there’s been a massive defunding of public higher education. In Texas, for example, between 2006 and 2016, higher education funding increased by .9%, whereas statewide all articles of funding increased by 44.5%. In 25 years of declining state support for public colleges, the University of Illinois Chicago has gone down by 35 points. The University of California Davis by 33 points. And this list goes on and on and on. University of Virginia right now is down around 5% state support. The University of Oregon I’m told by a good friend there is between 5% and 9%.

Hickman: So basically you have forces that are trying to-

Cashio: Yup.

Hickman: … strangle state supported higher education.

Weber: Wow. Well, Larry, let’s talk about this issue of state support, for instance. It’s definitely the case that people have been pushing for less and less of it. That then has to be taken up somewhere, and one answer is that goes to individual students who then take on all this debt. This brings us back to your point about when you had to pay $50, right? What do you think of the prospects for regaining public support so that people don’t have to take on all this debt we’re taking on? Is it plausible? Do you think that that’s the road forward, is to try and be advocates for getting more support for our education? Is that the issue, or what are the-

Hickman: Yes, but-

Weber: Go ahead.

Hickman: That’s part of the issue. It will be an uphill battle, I think, because legislators have an interest in doing this. The people they work with in terms of the lobbyists have deep pockets, and those deep pockets sometimes spill over into the campaign contributions.

Weber: Well, I want to-

Hickman: So, there’s a part of the problem.

Weber: Right. I want to follow up. There was a movement in some states to have community college, two-year college, actually paid for. Including actually in Mississippi there was discussion about seeing whether or not community college could be free to any person of the state. Is that, do you think, a solution, or is that a smoke screen? That kind of thing.

Hickman: Undergraduate tuition through two-years, four-years, should be free. Bernie Sanders said that, the Clinton campaign said that. I picked up some interesting data from an article in the New York Times that I will share with you involving taxes. The top 1% economically in the United States pay about a third of their incomes to the fed government. I’m not talking about assets here. That’s a different matter that Thomas Piketty addressed in his book Capitalism in the Twenty-First Century. We could talk about that if we have time.

Hickman: But the point is, if you took the Tax Policy Center, which is a joint project of the Urban Institute and the Brooking Institutes, both middle of the road institutions. If you took the top 1%, which includes about 1.13 million households earning an average income of about $2.1 million, raising the tax burden from 30% to 40% would generate about $157 billion in revenue the first year. Increasing it to 45% brings in a whopping $276 billion. If the tax increases were limited to just the 115,000 households at the top .1% with an average income of $9.4 million, and a 40% tax rate, you’d get $55 billion.

Hickman: You know what that would pay for? It would pay for eliminating undergraduate tuition at all the country’s four-year public colleges and universities. And, you would have money left over to help fund universal pre-kindergarten.

Weber: Wow.

Hickman: That’s what needs to happen.

Weber: Well, everybody, I hope you’re thinking about tuition and higher education and the problems we face. You are listening to Philosophy Bakes Bread with Eric Weber, my cohost Anthony Cashio, and our great guest today, Dr. Larry Hickman. Thanks everybody for listening. We’ll be right back after a short break.

Cashio: Welcome back, everyone, to Philosophy Bakes Bread. This is Anthony Cashio and Eric Weber, and it is our privilege today to be talking with Larry Hickman. We’ve been talking about John Dewey, his philosophy on democracy, on education, and in the last segment we heard a lot about the more systemic problems in contemporary ways of approaching education in America.

Cashio: In this last segment, we’re going to have a final big picture question or two for Larry as well as some lighthearted thoughts. I hope they’re lighthearted. And we’ll end with a pressing philosophical question for our listeners as well as with some information about how to get ahold of us.

Cashio: Larry, you really did paint a kind of a scary picture of the teaching to the test model of the systemic problems that are found in contemporary approaches to American education. What can we do? As we work to fix these problems, what can we do? As I’m a parent, I’ve got a kid in fourth grade. I got a kid in kindergarten. I’m sure I’m not the only one who’s in this situation who wants to help democratize their children’s education, but at the same time, and there at the school they’re getting taught to the tests. They get this all the time. In Virginia they have what is called the SOLs, and they just have to learn how to take them. They spend all this time taking them.

Cashio: So, is there something I can do at home, or any of our listeners can do at home, to sort of work against this? If they’re not getting the sort of democratized education, they’re not learning who they are, experimenting with themselves at the school, what can parents or guardians do at home to help them [crosstalk 00:44:24] encourage democratic thinking?

Weber: They’re actually called SOLs?

Cashio: SLOs. Not SOLs. I’m sure, I might … I’m sure, I might call them SOLs. I just got used to it.

Weber: That’s funny.

Hickman: Well, I think there’s a couple things. You can vote for school board in school board elections. You can vote in state and national elections. That would be the obvious thing. But second, make sure your children read, and not only that, but they are able to read critically. That’s an important thing.

Hickman: Also, although I’m not entirely in favor of homeschooling because of socialization problems, I would say that there is some element of homeschooling you can do while your children are in school, and it is providing them with opportunities to explore diversity, to come in contact with people who are not like them that they have to come to terms with in terms of their perhaps prejudices or prejudgments.

Hickman: I’d say there’s a lot you can do. I don’t have any kids myself, but I have spent an entire career working with not only individuals in higher education, but also visiting schools and that sort of thing, and reading widely in the philosophy of education, and in educational practice. This is what I would recommend.

Cashio: All right. Reading-

Weber: Very nice.

Cashio: … and critical reading. That’s something I can do. I’m pretty good at that.

Hickman: And by the way, I include in reading access to all those forms of media. Critical view to media, that is one of the most important things you can teach your kids right now. That is to be critical and to view social media with a jaundiced eye.

Weber: Very nice. And by critical, you don’t just mean a kid who talks back to mom and dad, but someone who can think about-

Hickman: Well, critical has … There’s an old joke by the way about a kid who’s going to theological seminary. He comes home and he talks to his local pastor. The pastor says, “So what are you doing?” He says, “Well, I’ve got a course in Biblical criticism.” The pastor says, “Why would anybody want to be critical of the Bible?” That’s the sense in which I mean critical. That is, looking at it with a very careful eye trying to understand it.

Cashio: Right.

Weber: Very nice. Thanks for the explanation.

Weber: So, some people out there would think that belief or, to put it another way, faith in democracy is naïve, right? That democracies can make crazy decisions. In fact, there was a lot of criticism and has been a lot of criticism in the United Kingdom, including Sir John Major apparently, who branded the majority of voters stupid for choosing Brexit, he thought, right? Are we foolish to have faith in democracy? Is faith in democracy naïve?

Hickman: No, I don’t think faith in democracy is naïve. It would be naïve to think that democracy works all the time, because it doesn’t. In fact, there are no perfect democracies. There are always setbacks.I’ve got a thing I’ve memorized that Dewey said that I think really kind of sums up a lot of this. And this was, by the way, what he said in 1939. Now, you think about what was going on in 1939. The world looked really bad. The rise of Hitler, Mussolini, of the Axis powers, a retreat from democracy much as what we’re seeing now in places like Poland and Hungary and elsewhere.

Hickman: Dewey said, and this is almost a direct quote, “Belief in democracy is belief in the ability of human experience to generate the aims and methods by which further experience can grow in ordered richness.” And that is democracy. Democracy is not a form of government. It is a way of living together. It’s a form of life. It’s a way of treating our fellow human beings, and that can take place at very basic levels, and grow into larger structures.

Weber: What does this mean, this notion of growth into ordered richness? What does that mean for the person who didn’t quite understand that?

Hickman: Ordered richness, there are two concepts there. Ordered means that you are taking the rough edges off of your experience. You’re trying to find ways of making the experience better. Richness means that your experiences branch out into new areas, areas in which you may not be comfortable, but which provide the material for further growth. It’s a reciprocal relation between the order and the richness.

Weber: Very nice. Well, Larry, I understand you have a passage you wanted to read to us from Dewey about democracy in education that’s relevant for listeners today. Do you want to go ahead and read that to us?

Hickman: Yes. Let me go ahead and do that. This is in response to the growing call for vocational education, and even in some cases in the UK for courses to be priced in terms of future projected incomes. Think about that.

Hickman: Here’s Dewey. Put in concrete terms, there’s danger that vocational education will be interpreted in theory and practice as trade education as a means of securing technical efficiency in specialized future pursuits. Sound familiar? Education-

Weber: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Cashio: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Hickman: … would then become an instrument of perpetuating unchange, the existing industrial order of society, instead of operating as a means of its transformation. The desired transformation is not difficult to define in a formal way. It signifies a society in which every person shall be occupied in something which makes the lives of others better worth living, and which accordingly makes the ties which bind persons together more perceptible, which breaks down the barriers and distance between them. It denotes a state of affairs in which the interest of each in his work is uncoerced and intelligent based upon its congeniality to his own aptitudes.

Hickman: I don’t see how you can get that without the study of the humanities, liberal arts, and the arts. To have mere technical education is training; it is not education.

Cashio: The liberal arts is sort of a vocational training.

Hickman: Liberal arts might be vocational training for those who plan to teach. For others, the liberal arts are essential for those people who want to understand themselves, their communities, and the way forward.

Weber: Very nice.

Cashio: Larry! One of our final questions comes from the inspiration for our show, which is to say philosophy bakes bread. Would you say that philosophy bakes no bread, that it is not practical as the famous saying go, or that it does? I think our listeners and me and Eric kind of have a pretty good feel about where you’re going to go with this, but we’re always surprised. We like to ask this of all our guests. What do you think? Does philosophy bake bread?

Hickman: Well, I would say that philosophy is one of the most important bakeries that we have because as far as the question of practicality goes, it is philosophy which has as one of its tasks the determination of the relationships between practice and theory. That’s what philosophers do, and if that’s not baking bread, I don’t know what it is.

Weber: All right. Well, we have another segment. Our penultimate, I guess, our before last segment is called [philosophunnies 00:51:26]. We want to make sure that people know both the serious side of phil, Larry, as well as the lighter side. We’re going to ask you if you’ve got a funny joke or a story to tell about philosophy.

Weber: Say philosophunnies.

Speaker 5: Philosophunnies.

Weber: Say philosophunnies.

Speaker 5: [inaudible 00:51:49].

Weber: Larry, have you got a funny joke or a funny story to tell about philosophy, or about John Dewey, or about democracy in education, any of that? Do you have a joke or a funny story for us?

Hickman: I do have a story, and your listeners will have to judge for themselves whether it’s funny or not.

Weber: Okay.

Hickman: This does have to do with one of the themes we talked about, the kind of testing theme. In fact, more specifically, Dewey’s ideas about intelligence testing. That is, IQ testing.

Hickman: Dewey once said that IQ testing reminded him of what they did when he was a boy in Burlington, Vermont. They would catch a hog, and then they would go to one of those wooden fences, log fences, and they put a board across the fence. They’d put the hog on one side of the board. On the other side of the board they would put rocks until the hog and the rocks equaled out. Then they would turn the hog loose and guess the weight of the rocks.

Hickman: He thought that that was basically the idea behind IQ testing. It was spurious, and it didn’t lead anywhere. Dewey’s idea about testing is like medical testing. You do not compare one student to another in terms of medical testing. You try to address the issues that the student has on his own terms. This broad-based testing is just, it is a bad educational process.

Weber: Well, very interesting, and there’s been more and more talk lately about Charles Murray and the bell curve and IQ testing, and recent conflicts about that. I’m glad you brought up a joke, or a story anyway, about Dewey talking about IQ testing especially.

Hickman: We should have stopped paying attention to Charles Murray 20 years ago.

Cashio: Maybe sooner.

Weber: Well, Larry, I actually have a story to tell. This is unusual, right? I remember … for the philosophunnies section, I remember way back when taking a class with Larry Hickman. I believe it was a course on William James actually, one of basically John Dewey’s friends and colleagues from a distance. At one point, Larry said, “Hey, you know, I’m open to any criticisms of Dewey, and I want to hear what you all have to say.” I think what you said literally was, “I’m not a card-carrying Deweyan.” The funny thing to my mind was I thought about your business card, the director of the Center for Dewey Studies. I thought to myself, “Well, you kind of are a card-carrying Deweyan.”

Hickman: Well, I [crosstalk 00:54:15]. Let me-

Weber: Literally speaking.

Hickman: Let me say that I think Dewey would’ve agreed that it applies to him as well as to the Buddha, what the Buddha said: If you meet the Buddha on the road, kill him.

Cashio: Oh boy.

Weber: What?

Hickman: That is, the ideas have to be your-

Cashio: That’s one of my favorite commands.

Hickman: Your ideas have to be your ideas. You have to do it for yourself; nobody can do it for you.

Weber: I like it. All right. That’s funny.

Hickman: Even great ideas have to be improved. Yes. Thank you for that reference to the card, by the way. Philosophers can also be very critical of themselves. They can make fun of themselves. They can satire themselves.

Hickman: One of the philosophers I know told a story about a dean of a college of science who is addressing the incoming scientists for which he’s raised enormous amounts of startup funds because of all their equipment. He says, “Now, I want to know. You know, you guys are so expensive in your startup costs. I want to know why you can’t be like mathematicians. All they need is a pencil, a piece of paper, and a wastebasket to throw away the stuff that doesn’t work. Or better yet, be like philosophers. All they need is a pencil and a piece of paper.” So philosophers can make fun of themselves.

Weber: I love it.

Cashio: Well, Eric and I dug up a few democracy-based political jokes kind of anticipating the theme, but you know, I don’t approve of political jokes. I’ve just seen too many of them get elected.

Hickman: Oh, okay. All right.

Weber: America is a country which produces citizens who will cross the ocean to fight for democracy, but won’t cross the street to vote.

Cashio: Larry, did I ever tell you about the dream I had about John Dewey when I was studying for the prelims?

Hickman: That sounds interesting.

Weber: No.

Cashio: You know what? I don’t know if it’s funny or not, but I’d been studying about aesthetics, so I’d been studying about art all day. Hegel and Dewey. And in my dream I walked into this house, and John Dewey was standing there. He had big buckets of, it looked like red paint or blood, and he was just smearing it all over the wall. He had his shirt off and he looked at me. He had a pretty epic mustache, so he’s got, you know, the blood dripping from his mustache. He just wipes his hand on his face and looks at me. He goes, “Art! Don’t you see that it’s art?”

Hickman: I wish you hadn’t told me that.

Weber: There we go.

Cashio: For our listeners, the prelims are a really difficult test that kind of lead to fever [crosstalk 00:56:49] dreams apparently.

Weber: “I wish you hadn’t told me that.” I love that.

Cashio: Well, last but not least, we do want to take advantage of the fact that today we have powerful social media and technology that allow two-way communications even for programs like radio shows. So, we want to invite our listeners to send us their thoughts about big questions that we raise on the show.

Weber: That’s right. Given that, Larry, we’d love to hear your thoughts to see if you’ve got a question that you’d propose we ask our listeners. We have a segment we call You Tell Me, which we often put in Breadcrumb episodes. We’d love to know whether you have a question you’d propose for our listeners.

Hickman: I do, and it’s a question that’s been made fun of, but I ask it in considerable … I ask it very seriously because I think I’ve got an answer to it, and I want to see what the other answers are.

Weber: Oh.

Hickman: And that is, what is the meaning of life?

Cashio: Ooh. Oh boy.

Weber: In 37 episodes, we haven’t had that question come up. That’s right.

Cashio: We’re going to have you back on and answer that one.

Hickman: I can tell you [crosstalk 00:57:54] at some point what my answer is.

Weber: We might have to record a Breadcrumb on that. I love it.

Cashio: I think so. We’ll keep that [inaudible 00:58:00]. I like the mystery, though. Let’s leave it. All right, listeners, we want to know what is the meaning of life? I love it very much.

Weber: I love it.

Cashio: All right. Well, thank you everyone for listening to this episode of Philosophy Bakes Bread, food for thought about life and leadership. Your hosts, Dr. Anthony Cashio and Dr. Eric Weber, are really grateful to have been joined today by the great Dr. Larry Hickman.

Hickman: Glad to be here.

Cashio: Thank you, Larry. It’s been a wonderful discussion. Really thank you for joining us.

Weber: Thank you so much.

Cashio: We hope you listeners will join us again. Consider sending us your thoughts about anything you’ve heard today that you’d like to hear about in the future, or about the specific question we raised for you: what is the meaning of life? You know what, Eric? You know what I also want to hear about? If our listeners have a good joke. Sometimes they say, “I want to hear jokes. What’s going on with those?”

Weber: I like that idea.

Cashio: Send us your jokes. If you think you’ve got a good joke that’s clean enough to say on the air, send it our way and we’ll share it and we’ll give you credit and everything. All right? So, there you go.

Weber: That’s right. Remember everybody, you can catch us on Twitter, on Facebook, and on our website at PhilosophyBakesBread.com, and there you’ll find transcripts for our many episodes thanks to Drake [Bolling 00:59:07], an undergraduate philosophy student at the University of Kentucky.

Cashio: Thank you, Drake.

Weber: That’s right. And one more thing, folks. If you want to support the show and to be more involved in the work of the Society of Philosophers in America, SOPHIA, the easiest thing to do is to go join as a member at philosophersinamerica.com. You can go just learn about it anyway. And for what it’s worth, we just learned, and it’s been announced that SOPHIA has won a major award from the American Philosophical Association called the APAPDC prize-

Hickman: Congratulations.

Weber: … for excellent in innovation and philosophy programs. How about that?

Cashio: Woo hoo! That’s really great news.

Hickman: That’s great.

Cashio: Fantastic. Well, if you’ve enjoyed the show and you’re still enjoying the show, it would mean a lot to us if you’d take a second to rate and review us on iTunes or your favorite, I guess, podcast listening service. You know, those good reviews help us work with the algorithms they use to share it with others.

Cashio: And you can always of course email us at PhilosophyBakesBread@gmail.com. You can also leave us a short recorded message with a comment that we may be able to play on the show at 859-257-1849. That’s 859-257-1849.

Cashio: Join us again next time on Philosophy Bakes Bread, food for thought about life and leadership.

Radio announcer: Hey there. If you’re enjoying this podcast from WRFL Lexington, you may enjoy our live radio stream at WRFL.fm, and of course via radio at 88.1 FM in the central Kentucky area. We have a wide variety of programs you’re sure to enjoy. Just go to WRFL.fm/schedule and see what programs appeal most to you. Thanks again for listening to this podcast from WRFL Lexington.