| By Bertha Alvarez Manninen |

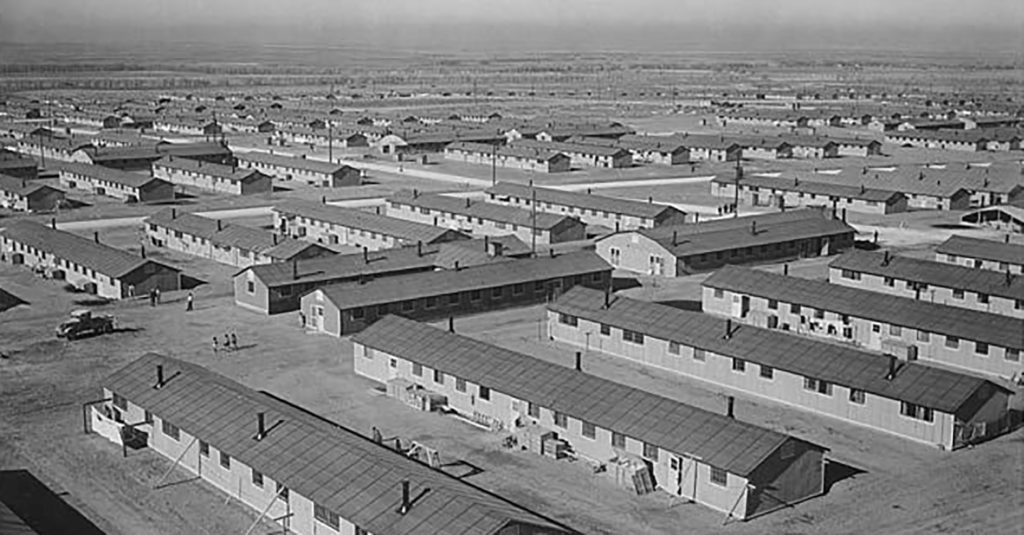

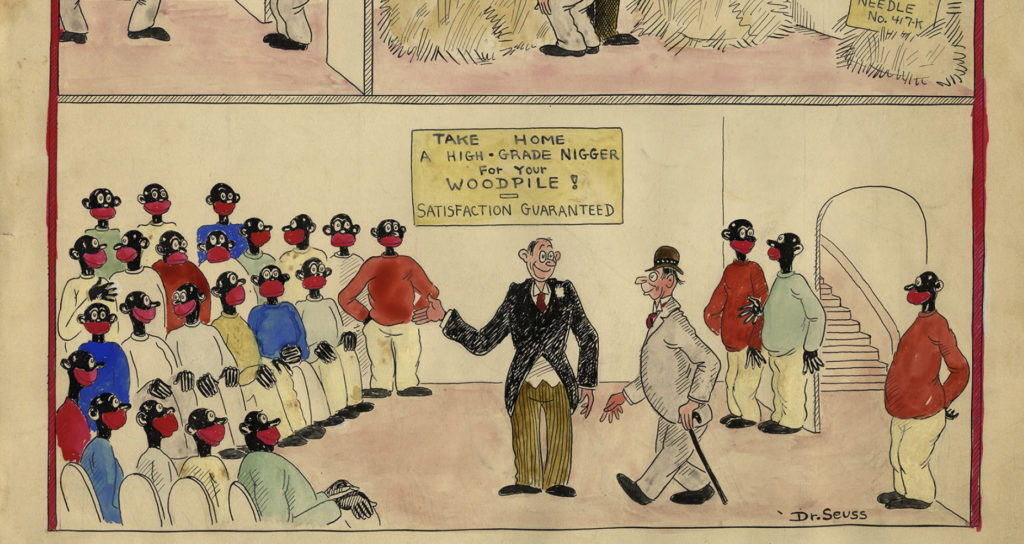

Theodor Seuss Geisel, known simply as Dr. Seuss, remains one of the most widely beloved children’s authors of all time. Yet not many know that his contributions consisted of far more than fun or educational bedtime stories. During World War II, Seuss drew many cartoon editorials targeting the Germans and the Japanese. One pervasive theme throughout these cartoons was the display of “our enemies” as animals. Seuss often illustrated the Germans as alligators, piranhas, sea monsters, dogs, and snakes; the Japanese were drawn as monkeys doing Hitler’s bidding, or as sly cats infiltrating the United States.[1] In other words, our enemies were subhuman. This kind of sentiment permeated our culture at the time. In 1942, an editorial published in the Los Angeles Times argued in favor of the forced internment of American citizens of Japanese ancestry, stating that “a viper is nonetheless a viper wherever the egg is hatched — so a Japanese-American, born of Japanese parents — grows up to be a Japanese, not an American.”[2]

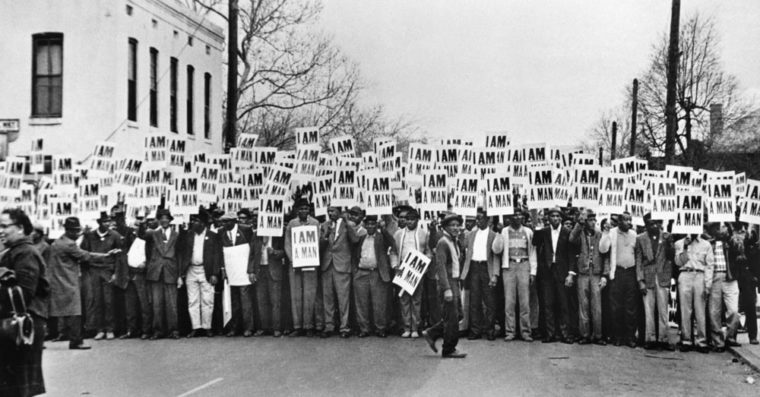

Photo credit: colorado.gov.

The tendency to describe “enemies” as animals is part of the process of dehumanization. According to social ethicist Herbert Kelman, in order to understand how dehumanization functions, it is important to first “ask what it means to perceive another person as fully human, in the sense of being included in the moral compact that governs human relationships” (Kelman, 48).[3] Kelman notes that in order to perceive others as full members of our moral community, it is necessary to recognize them both as autonomous individuals who are “capable of making choices, and entitled to live his own life on the basis of his own goals and values” (Kelman, 48) and also as “part of an interconnected network of individuals who care for each other, who recognize each other’s individuality, and who respect each other’s rights” (Kelman, 48-49). In this sense, dehumanizing another person isn’t about literally denying their humanity (perpetrators of dehumanization would likely still view their victims as members of the species Homo sapiens); it is about denying their moral significance.

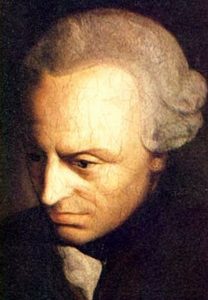

In this paper, I want to explore a more interdisciplinary approach to studying the problem of dehumanization. While existing literature on this issue typically focuses on the psychology of dehumanization, and the historical acts of violence often correlated with it, I am further interested in what ways philosophy can be used to combat the human tendency to rationalize causing suffering to others through the removal of their moral worth. More specifically, I want to explore how the ethical writings of Immanuel Kant, Soren Kierkegaard, and Emmanuel Levinas can help us re-humanize those who have been dehumanized.

A Brief Overview of Dehumanization

Immanuel Kant, who we shall discuss below, made it a cornerstone of his ethical imperative to respect all rational creatures. We are not permitted, Kant tells us, to treat rational, autonomous agents as mere instruments for our own ends. Because human beings can set their own end in accordance with the moral law, human nature commands respect. We are to treat all humans not as mere instruments, but as ends in themselves.

And yet, even Kant did not follow his own moral imperatives as well as he should have. He argued that women were incapable of acting according to rational moral principles; that when they did act in accordance with the moral law, it was solely due to aesthetic reasons (because “the wicked… is ugly… nothing of duty, nothing of compulsion, nothing of obligation!). Because Kant associated moral value and worth with the capacity for rationality, women’s alleged compromised capacity for rational agency entailed that their moral status is equally compromised. Women only have access to full moral worth via their relationship to the men in their lives (fathers or husbands), and, in marriage, men are to control their wives and tell her “what [her] will is.”[4] In addition to his attitude against women, Kant also harbored incredibly racist views. He argued that Native Americans were not capable of being educated, and that persons of African descent were only capable of being educated as servants or slaves.

What this shows is that even those of us who may have claim to being more ethically aware are still capable of harboring morally problematic views, including ones that encourage the “otherization” of fellow humans. Kant encouraged the servitude and slavery of fellow human beings, which we know causes much suffering, because he did not attribute to them the properties that he thought were essential for moral status. History bears out that so many have done the same, often in a way that influences barbaric results.

These are not just mere images or words. Philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein emphasized how our language shapes the boundaries of our minds and thought: “the limits of my language mean the limits of my world” (Wittgenstein, 5.6).[6] Smith puts it this way: “[d]ehumanization isn’t a way of talking. It’s a way of thinking… [i]t acts as a psychological lubricant, dissolving our inhibitions and inflaming our destructive passions. As such, it empowers us to perform acts that would, under other circumstances, be unthinkable” (Smith, 13). Kelman highlights the connection between violence and dehumanization by focusing on how indulging in the latter decreases our sense of empathy and care for those we regard as “the other”:

Sanctioned massacres become possible to the extent that we deprive fellow human beings of identity and community. It is difficult to have compassion for those who lack identity and who are excluded from our community; their death does not move us in a personal way. Thus when a group of people is defined entirely in terms of a category to which they belong, and when this category is excluded from the human family, then the moral restraints against killing them are more readily overcome” (Kelman, 49).

When we dehumanize others, when we stigmatize them as either lacking in agency or individuality, or as not belonging to our moral community, we are less likely to develop feelings of empathy or care for them. There is even neurological evidence of this. One study noted that:

[M]embers of extreme out-groups are so dehumanized that they may not even be encodedas social beings. When participants viewed targets from highly stigmatized social groups who elicit disgust, the region of the brain typically recruited for social perception (the medial prefrontal cortex) was not recruited. Those who are the least valued in the culture were not deemed worthy of social consideration on a neurological level. … [T]here is a neurological correlate to extreme social devaluation and moral exclusion (Goff et al, 293-294).[7]

It is harder to harm someone when we see them as “one of our own.” Therefore, when we cease to view “the other” as such, we erase them from moral consideration, thereby rendering their injury more morally palatable. Elliot Aronson writes:

[I]f we have done something cruel to a person or a group of people, we derogate that person or group in order to justify our cruelty. If we can convince ourselves that a group is unworthy, subhuman, stupid, or immoral, it helps us to keep from feeling immoral if we enslave members of that group, deprive them of a decent education, or murder them. We can then continue to go to church and to feel like good Christians, because it isn’t a fellow human we’ve hurt (Aronson, 127).[8]

Often, when we read about these historical acts of violence, we may be tempted to write them off as anomalous behavior, as something so horrific that the “average” person would be incapable of replicating. Smith warns against this – the Nazis, he argues, were neither “monsters nor madmen” (Smith, 133) – but rather unremarkable, rather normal, people (one important side note I want to emphasize is that the tendency to blame mental illness for horrendous actions not only serves to ostracizes already vulnerable members of our community, it ignores the fact that persons suffering from mental illness are ten times more likely to be victims of violence than the general population[9]). Recognizing the “normal-ness” of those who commit horrific acts of violence, and noting just how common those instances of violence go hand-in-hand with dehumanizing language and thought, highlights just how easy it can be for any one of us to follow a similar path. Croatian journalist Slovenka Drakulic emphasizes this: “the more you know them… the more you realize that war criminals might be ordinary people, the more afraid you become. Why? This is because the consequences are more serious than if they were monsters. If ordinary people committed war crimes, it means that any one of us could commit them” (Smith, 135). No one is immune from the phenomenon of dehumanization – “we are all potential dehumanizers, just as we are all potential objects of dehumanization” (Smith, 25).

Photo by Vas Panagiotopoulos, 2016. Creative commons license.

These examples should not be relegated to the history books; the phenomenon of dehumanization continues even in the contemporary United States. One of the latest incarnations of this kind of language can be seen in the speeches of Richard Spencer, one of the public faces of the “alt-right” movement, where he openly questions the humanity of Jewish persons: “one wonders if these people are people at all, or instead soulless golems…” While most of us are not guilty of mass genocide, or bigoted violence, many of us have used racial or ethnic epithets or slurs which, in the words of Richard Delgado, “remains one of the most pervasive channels through which discriminatory attitudes are imparted. Such language injures the dignity and self-regard of the person to whom it is addressed” (Delgado, 135-136).[10] Using such slurs contributes to the dehumanization of others, in a similar manner as we have seen above when referring to humans as animals, because it effectively serves to erase the individuality of a person and render him nothing more than a faceless member of a group one hates or derides. When one uses racial or ethnic slurs as a method of insult, “we are less likely to consider [the subject] an individual, and more likely to think of him only as an out-group member” (Allport, 91).[11]

Randall Kennedy. Source: lawyersgunsmoneyblog.com.

We are all familiar with the most common uses of these terms (the “n” word, for example, is described by Harvard University professor Randall Kennedy as “the atomic bomb of racial slurs”). Yet let’s consider a more contemporary example that is viewed by many as innocuous: referring to undocumented workers in the United States as “illegals.” By taking an adjective and turning it into a noun, we are effectively taking an unlawful action and using it to denote an unlawful person. Many of us are guilty of legal violations to various degrees – I stole a box of crayons as a kid, a package of soap as a teenager when my family couldn’t afford it, and although I no longer steal, I have been known to definitely violate clearly posted speed limits. Yet I am never referred to as “an illegal”; my personhood is never questioned because of these infractions.

One common defense of the use of such a term is that it is an accurate depiction of a person’s immigration status – but so is the term “undocumented immigrant.” Yet there is a marked distinction in the attitude towards these individuals from the people who use the former term rather than the latter. In a New York Times op-ed, Lawrence Downes describes it well: “since the word modifies not the crime but the whole person, it goes too far. It spreads, like a stain that cannot wash out. It leaves its target diminished as a human, a lifetime member of a presumptive criminal class.”[12] It’s not about the accuracy of the term, but rather how the term is used. In Jane Elliot’s famous “blue-eyed/brown-eyed” experiment, where she puts her third-grade students through a two-day experiential trek through racism, the students wearing the collars for the day (a sign of their “inferiority”) were subjected to taunts from the collar-less, “superior,” students. In one incident, one child hits another because he was deridingly called “brown-eyed.” Although an accurate description of the boy’s eye color, the term effectively functioned as a kind of slur: it was used to demean him by emphasizing and mocking the trait that allegedly made him inferior.

From Debate.org.

Evidence that such disparaging language against undocumented immigrants is having an effect on the way they are treated is easily available. Consider how in 2014, the United States faced an influx of thousands of unaccompanied minors trying to cross the southern border. The children were mainly from South America, and were fleeing unspeakable poverty, hunger, and violence in their home countries. President Barack Obama, at the time, referred to this as an “urgent humanitarian crisis.” Not everyone felt the same way. The following is a sample of the language used against these children in public discourse (curse words have been removed):

“To hell with these scummy, smelly __ and send them back to where the hell they came from and take their diseases and drugs back with them!”

“… these ILLEGAL INVADERS are… easy to find, just go to the welfare office, the free clinics, schools, or Home Depot!”

“Come to my house I’ll take care of your illegal __ . NO questions asked. I’ve got a nice deep hole for you.”

“We are seeing the intentional destruction of America!! Wake up…. time to fight back. We won’t stop them with votes…..it will take bullets!!”[13]

From this one example, it is easy to see Smith’s and Kelman’s concerns playing out: how easy it is to slide from dehumanizing language to calls for violence, even against children, whom, in general, society often tends to treat with a much gentler hand.

Even seemingly innocuous bigoted jokes have been shown to have a negative effect on a person’s behavior. One study noted that “disparagement humor fosters discrimination against groups for whom society’s attitudes are ambivalent. [For example], participants higher in anti-Muslim prejudice tolerated discrimination against a Muslim person more after reading anti-Muslim jokes than after reading anti-Muslim statements or neutral jokes” (Ford et al., 178).[14] Another study noted that exposure to sexist humor increased tolerance of sexist behavior towards women in men who already displayed hostile sexist behavior.[15] Interestingly enough, however, the use of racial humor as a method of challenging and exposing bigotry may result in an opposite effect – of undermining those prejudices instead of subtly (or not so subtly) celebrating them.[16]

How Philosophy Can Help Re-Humanize the Dehumanized

Kant

Kelman notes that part of the process of rehumanizing the dehumanized is to see each human being as an individual, and to regard him as “an end in himself, rather than a means to some extraneous end. Individual worth, of necessity, has both a personal and a social referent; it implies that the individual has value and that he is valued by others” (Kelman, 49). Although, as abovementioned, Immanuel Kant failed to follow his own imperative when it came to anyone who wasn’t a white male, this does not mean that the imperatives have no merit. Treating human beings as ends in themselves, respecting the intrinsic value of their humanity rather than treating them as mere instrument for one’s own end, is the cornerstone of Kantian ethics.

Kant does argue that all human beings possess intrinsic dignity as a result of our rational nature (a nature in which all humans equally share, despite Kant’s erroneous contention otherwise). It is because of our capacity for rationality that we can create our own autonomous goals and ends, and part of respecting each other as persons is respecting those ends in others as we would our own (Kant, 6:392). [17] Moreover, we ought never to engage in any action that robs any one of us of our humanity. Instead, we should “act in such a way that you use humanity, whether in your own person or in the person of any other, always at the same time as an end, never merely as a means” (Kant, 4:429).[18] While loving all human beings can never be a duty, according to Kant (in contrast to Kierkegaard) because we cannot command feelings, acting beneficently is indeed a moral obligation, while its contrast, acting hatefully, is a moral infraction: “to do good to other human beings insofar as we can is a duty, whether one loves them or not… hatred of them is always hateful, even when it takes the form merely of completely avoiding them (separatist misanthropy), without active hostility toward them. For benevolence always remains a duty…” (Kant, 6:402). Kantian ethics, then, demands that we regard other human beings in one of the ways that Kelman argues is necessary in order to combat dehumanization.

Knowing what we do about the psychological effects of using racial or ethnic slurs to demean “the other” entails at least two moral obligations from a Kantian perspective. First, the slurs themselves are dehumanizing, and as such using them is a violation of Kant’s imperative. However, the fact that such language serves as a kind of “psychological lubricant” that makes harming others easier means that allowing yourself to engage in this kind of thinking increases the likelihood of engaging in demeaning and violent behavior against individuals whom are the target of such language, or, at the very least, of viewing such behavior against them as justified. As such, it isn’t just that the slurs themselves are harmful to others, it is also that the use of such slurs creates a predisposition in oneself to act in ways that violate the imperative to treat persons as ends in themselves. Kant argues that persons have duties of self-improvement, which includes cultivating your character to be of the kind that is inclined to follow the moral law (Kant, 6: 387). As such we should take great care not to allow ourselves to engage in any kind of behavior or thinking that makes it easier to dehumanize others. That is, we have a moral obligation not to engage in racist or bigoted thinking or language not just because it harms others directly, but also because it creates in us the kind of character that is more likely to either engage in, or overlook, dehumanizing treatment against others.

Kierkegaard

Samuel Gaertner and John Dovidio write that the tendency humans have to form “we/they” categorizations of other persons is exacerbated with “increased awareness of the intergroup boundary… at the intergroup level, people act in terms of their social identity… Outgroup members, in particular, become depersonalized undifferentiated, and substitutable entities” (Gaertner and Dovidio, 245).[19] They also note that, in cases of racial tensions, one way to help overcome disdain is to emphasize a “shared group identity.…[This] development of a sense of partnership can eliminate manifestations of even subtle, indirect, and rationalizable forms of racism” (Gaertner and Dovidio, 249). In another of their writings, Gaertner and Dovidio argue that their research on racism and bias shows that “the recategorization of different groups into one group as a particularly powerful and pragmatic strategy for combatting subtle forms of bias. Creating perception of common ingroup identity not only reduced the likelihood of discrimination based on race but also increases the likelihood of positive interracial behaviors” (Gaertner and Dovidio, 7).[20] In other words, refocusing attention on underlying commonalities, rather than emphasizing differences, decreases the perception of intergroup boundaries, which, in turn, decreases the tendency to “otherize” outgroup members.

Suppose there was a way to create the perception that all human beings are part of the same “ingroup”; that, despite our differences, our commonalties are much more formative in our identities. The writings of Søren Kierkegaard in his seminal book Works of Love attempts to do just this, with a focus on analyzing the Biblical commandment to love the neighbor as the self.

Kierkegaard spends a lot of time on the question of who, exactly, counts as a “neighbor” for the purposes of fulfilling this commandment; just who is the subject of the deep moral concern and divine love God commands of us. Kierkegaard’s answer is radically egalitarian – “the neighbor” includes “all men, unconditionally all… (Kierkegaard, 63). [21] Human beings, even our “enemies,” have a shared commonality and likeness because we are made in God’s image. Therefore, “to love one’s neighbor means equality… your neighbor is every man… he is your neighbor on the basis of equality with you before God; but this equality absolutely every man has, and he has it absolutely” (Kierkegaard, 72).

This kind of love, commonly called agape love, is of a higher quality than erotic love, or love between friends or family members. These kinds of love, Kierkegaard argues, are love based on preference and are, therefore, as D. Anthony Storm puts it, “temporal…mere shadows of” real, unconditional, love.” Kierkegaard writes:

All other love, whether humanly speaking it withers early and is altered or lovingly preserves itself for a round of time—such love is still transient; it merely blossoms. This is precisely its weakness and tragedy, whether it blossoms for an hour or for seventy years—it merely blossoms; but Christian love is eternal (Kierkegaard, 25).

It is this kind of love that is truly unconditional. Loving other based on their relationship to you (loving your children, your parents, your fellow countrypersons, members of your own race, or ethnicity, or religion) is inherently selfish because it still places the self as the center of the moral universe. You love others to the extent that they are like you or have a relationship to you. But such love is often fleeting – once the similarity to you is dissolved for whatever reason, once someone who was once in your “ingroup” becomes part of your “outgroup”, the love you had goes with it. Dissolving such a distinction, so that all human beings become part of your “ingroup”, makes your love for them stable and more permanent – for if the only criteria for being part of the “ingroup” is just being a human being, that is a similarity that will never go away.

If Kierkegaard is right, if I am commanded by God to love, in the agape sense, every single human being, and to emphasize their similarities rather than their differences, then this has radical moral implications for engaging in any kind of language, behavior, or state of mind that not only de-emphasizes similarities, but robs others of their humanity altogether. One of the functions of slurs is to “provide a simple but toxic shorthand for marking boundaries between groups… all of this talk helps draw lines in between groups, forming us/them boundaries” (Myers and Williamson, 11).[22] This is the very opposite of what Kierkegaard argues God wants us to do. Rather, our differences should “hang loosely about the individual… when distinctions hang loosely in this way, then there steadily shines in every individual that essential other person, that which is common to all men, the eternal likeness, the equality” (Kierkegaard, 96).

I read Kierkegaard here as offering a recipe for the eradication of the bias, racism, sexism, and hate that permeates so much of our daily human interactions, and his suggestions are supported by the research that shows that focusing on a shared group identity helps to melt the distinctions that fuels such destructive behavior. One obvious limitation to applying Kierkegaard that he is speaking only to those who adhere to theistic beliefs, particularly Christian ones. It is the belief in God, and regarding all persons as being created in His image, that forms the foundation of Kierkegaard’s egalitarianism. However, it appears that his philosophy here can find a place in the secular realm, as seems evident in Gaertner and Dovidio’s research; humans indeed have fundamental commonalities that are not particularly religious in kind. In a beautiful analogy, Kierkegaard instructs us to view other human beings as pieces of paper that, while perhaps many kinds of writings are inscribed upon it, making each different from the other, all display a common watermark that you can clearly see when you hold it up to the light. Focusing on the differing inscriptions is what leads to “outgroup” prejudice, whereas emphasis on our “common watermark” is what will help combat it.

Levinas

As mentioned above, Gordon Allport notes that one function of slurs is that it allows us to depersonalize members of a derided group, which aids in viewing them in an abstract manner. This, in turn, makes it more difficult to feel empathy or compassion towards them. He writes:

One human being is, after all, pretty much like another – like oneself. One can scarcely help but sympathize with the victim. To attack him would be to arouse some pain in ourselves. Our own “body image” would be involved, for his body is like our own body. But there is no body image of a group. It is more abstract, more impersonal… this sympathizing tendency seems to explain a phenomenon we have frequently noted: people who hate groups in the abstract will, in actual conduct, often act fairly and even kindly toward individual members of the group (Allport, 92).

It is easier to hate persons when they remain abstract caricatures; to hate an actual human being, one who looks like you, acts like you, is just another version of you, is much harder. Confronting their humanity, being in a situation where one is forced to look the “other” in the eye, makes hatred that much harder.

This is one of the themes in philosopher Emmanuel Levinas’ work Totality and Infinity, where he implores us to always keep “the face” of “the other” firmly planted in our mind’s eye. Focusing on “the face” immediately calls us into an ethical relationship with that person: “the face is a living presence; it is expression… the face speaks to me and thereby invites me to a relation… the face opens the primordial discourse whose first word is obligation” (Levinas, 66-201). Recognizing the humanity in “the other” by forcing oneself to look at “the face” will demand that we treat each other with intrinsic dignity and worth. The focus on the face forces one to acknowledge that humanity, and to see “the other” as another version of your self. Racial slurs and dehumanizing language effectively erase “the face” from your mind and therefore from moral consideration – it becomes a kind of mask that you used to avoid looking at your fellow human as a fellow human. But when “the face presents itself [it] demands justice” (Levinas, 294) and once you start earnestly acknowledging the humanity of “the other,” you “are not free to ignore the meaningful world into which the face of the other has introduced to me” (Levinas, 219). That is, by looking another human being in the eye, by really looking at them, by refusing to engage in any behavior that paints them as anything less than another version of you, you will no longer be able to ignore their plight. When they become persons for you, looking out for their welfare becomes your moral obligation.

Photo by Geoffrey Fairchild, 2010. Creative commons license.

It is not easy, however, to have access to “the face” all the time; we are all familiar with the phrase “out of sight, out of mind.” While we readily ignore the horrible plights of persons in distant lands, we tend to be more sympathetic when a tragedy hits close to home. If Levinas requires access to “the face” to solidify moral obligation, wouldn’t that mean we are less likely to morally regard, say, others in distant lands to whom we have limited contact?

Here, our methods for disseminating images and information plays a crucial role. Fifty-three years ago, on March 7, 1965, African-American civil rights activists and protestors were severely beaten in their attempt to march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama in their quest to secure access to equal voting rights. In what has come to be known as Bloody Sunday, 600 peaceful marchers were attacked by Alabama State troopers as they crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge. The images of these beatings were televised and reached many in the United States who were largely unaware of these brutal treatments. Horrified, many Americans joined Dr. Martin Luther King and now-Representative John Lewis when they marched again on March 21, 1965, this time with federal protection. What started as a march of 600 people, grew to one of 3,200 when they started to march again, and to 25,000 by the time they reached Montgomery. The power of these images cannot be understated; from a Levinasian stand-point, these images provided “the face” that had for so many been absent, and those who were affected responded precisely in the way Levinas anticipates: by responding to their moral obligations towards people who were once the “other.”

Aylan Kurdi. Photo by Ur Cameras, Public domain.

In this sense, our contemporary technology can make up for the absence of “the face” in our immediate vicinity. Social media and “live streaming” is now a prominent way that people get their news, and we are we are more connected by these mediums than ever before. A contemporary example of the power of “the face” is that of Aylan Kurdi, the three-year-old toddler whose lifeless body washed ashore on a beach in Turkey after the boat he was traveling on with his family, while attempting to escape the violence in Syria, capsized. Aylan, his mother, and five-year-old his brother all drowned – only his father survived. A picture of Aylan face-down on the beach sparked outrage in many across the world, and put a face to the humanitarian crisis confronting Syrian refugees. British Prime Minister David Cameron vowed to “do more” to help the Syrians after the picture surfaced. Peter Bouckaert, emergencies director at Human Rights Watch, proclaimed that “we really need a wake-up call that children are dying, washing up dead on the beaches of Europe, because of our collective failure to provide safe passage.”[23] In response to Aylan’s death, countries such as Germany and Austria relaxed their immigration laws for fleeing refugees. This example illustrates Levinas’ point exactly: the tragic “face” of Aylan forced many to acknowledge their moral obligation to him and other refugees; it called many into a “relation” with him and the persons he represented.

But we do not have to go that far to see Levinas’ words in action. Today, there are many stories of individuals who voted for Donald Trump because of his stance on illegal immigration, and now are surprised and bemused to be witnessing individuals they know and care for being deported. When they viewed illegal immigrants as an abstract group, as an “out-group,” Trump’s stance was not a cause for concern; indeed, it was a cause for support. It took those policies affecting people they actually know, “faces” they actually see every day, people who are members of their “in-group”, to call those policies into question. One wonders how they would have voted had they seen those “faces” in other immigrants all along.

Conclusion

Image by Dr. Seuss, courtesy of The Huffington Post.

I began this paper by highlighting the racist editorial cartoons of Dr. Seuss, a person so endeared in our culture that learning about this history often surprises many. I want to end with yet another Dr. Seuss story – one that magnifies the impact of focusing on “the face” and our common “watermark” as a method of battling bigotry and dehumanization. In 1953, Seuss visited Japan, and was guided there by Mitsugi Nakamura, the dean on Doshisha University. Seuss’ visitation with Japanese persons, particularly children, deeply impacted his views. In 1954, Seuss published the book Horton Hears a Who! in an effort to, according to one analysis, “redress the American image of Japan” (Minear, 264). Indeed, Seuss dedicated the book to Nakamura. In Horton Hears a Who!, Horton is the only one who sees the Whos as persons, and therefore is the only one who cares about their welfare as he struggles to save Whoville. To everyone else, especially to the “big kangaroo” and her joey, who lead to the push to discredit Horton and destroy the Whos, the Whos are invisible – they quite literally do not exist at all from their perspective. This can be interpreted as a literal exposition of the psychological consequences of dehumanization as emphasized by Smith and Kelman, where the “other” is, for all intents and purposes, erased from the moral community. Yet Horton’s insistence on saving the Whos, even at a great cost to himself, highlights Levinas’ point that “the face” of “the other” presents us with moral demands that we are not free to ignore. Indeed, towards the very end, when the kangaroo and the others finally do hear the Whos crying to them, they immediately react to save them as well. Horton serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of dehumanization, as well as highlighting the ethical relationships that we form with each other when we acknowledge our common humanity.

All of us are guilty, to varying extents, of the moral infractions discussed in this paper. While we may not have been a party to genocide or other acts of violence, many of us have biases that inform our behavior, and we have laughed, or made, the occasional racist joke, or used, or thought, the occasional racial slur. Many of us are guilty of ignoring the suffering of distant others, and of creating “in-group” versus “out-group” boundaries benefitting those we prefer. These behaviors are all different only in terms of gradation, rather than kind. Taking steps to catch ourselves when we indulge in these behaviors, trying to not repeat them, or call out others when they do in our presence, is part of the process of rehumanizing those we have, in one way or another, dehumanized.

Notes

[1] Minear 1999. Richard Minear. Dr. Seuss Goes to War. New York: The New Press.

[2] “What the L.A. Times Meant to Say.” Available at: https://densho.org/la-times-meant-say/.

[3] Kelman 1973. Herbert Kelman. “Violence without Moral Restraint: Reflections on the Dehumanization of Victims and Victimizers.” Journal of Social Issues, 29 (no. 4): 25-61.

[4] Kant 2006. Immanuel Kant. Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

[5] Smith. 2001. David Livingstone Smith. Less Than Human: Why We Demean, Enslave, and Exterminate Others. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

[6] Wittgenstein 1999. Ludwig Wittgenstein. Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

[7] Goff et al. 2008. P.A. Goff, J.L. Eberhardt, M.J. Williams, and M.C. Jackson. “Not yet human: Implicit knowledge, historical dehumanization, and contemporary consequences.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 94 (no. 2): 292–306.

[8] Aronson 1998. Elliot Aronson. “Causes of Prejudice” in Hatred, Bigotry, and Prejudice (RM Baird and SE Rosenbaum, eds). Amherst: Prometheus Books: 127-140.

[9] MentalHealth.gov. “Mental Health Myths and Facts.” Available at: https://www.mentalhealth.gov/basics/myths-facts/index.html.

[10] Delgado 1982. Richard Delgado. “Words that Wound: A Tort Action for Racial Insults, Epithets, and Name-Calling.” Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review, 17: 133-181.

[11] Allport 1979. Gordon Allport. “The Nature of Hatred” in Hatred, Bigotry, and Prejudice (RM Baird and SE Rosenbaum, eds). Amherst: Prometheus Books: 91-94.

[12] Downes 2007. Lawrence Downes. “What Part of “Illegal’ Don’t You Understand?” New York Times. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2007/10/28/opinion/28sun4.html?_r=1.

[13] Corsi 2014. Jerome Corsi. “Children Crossing Border: Obama will take care of us.” Available at: http://www.wnd.com/2014/07/children-crossing-border-obama-will-take-care-of-us/.

[14] Ford et al. 2013. Thomas Ford, Julie Woodzicka, Shane Triplett, Annie O. Kochersberger, Christopher J. Holden. “Not All Groups Are Equal: Differential Vulnerability of Social Groups to the Prejudice-Releasing Effects of Disparagement Humor.” Group Process and Intergroup Relations, 17 (no. 2): 178-199.

[15] Ford 2000. Thomas Ford. “Effects of Exposure to Sexist Humor on Perceptions of Normative Tolerance of Sexism.” European Journal of Social Psychology, 31 (no. 6): 1093-1107

[16] Saucier et al. 2016. Donald Saucier, Conor O’Dea, and Megan Strain. “The Bad, the Good, the Misunderstood: The Social Effects of Racial Humor. Translational Issues in Psychological Science, 2(1): 75-85.

[17] Kant 1996. Immanuel Kant. Metaphysics of Morals. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

[18] Kant 1997. Immanuel Kant. Groundwork for the Metaphysics of Morals. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

[19] Gaertner and Dovidio 1986. Samuel Gaertner and John Dovidio. “Toward the Elimination of Racism: The study of Intergroup Behavior.” In Hatred, Bigotry, and Prejudice, edited by R.M. Baird and S.E. Rosenbaum, Amherst: Prometheus Books: 245-249.

[20] Gaertner and Dovidio 2000. Samuel Gaertner and John Dovidio. Reducing Intergroup Bias: The Common Ingroup Identity Model. New York, NY: Routledge.

[21] Kierkegaard 1962. Søren Kierkegaard. Works of Love. New York: Harper and Row Publishers.

[22] Myers and Williamson 2001. K. Myers and P. Williamson. “Race Talk: The Perpetuation of Racism through Private Discourse.” Race and Society, 4 (no. 2): 3-26.

[23] Morning Edition on NPR. 2015. “That Little Syrian Boy: Here’s Who He Was.” Available at: http://www.npr.org/sections/parallels/2015/09/03/437132793/photo-of-dead-3-year-old-syrian-refugee-breaks-hearts-around-the-world.