| By Darrius Hills and Seth Vannatta |

The Negro is a sort of seventh son, born with a veil, and gifted with second-sight in this American world,—a world which yields him not true self-consciousness, but only lets him see himself through the revelation of the other world. It is a peculiar sensation, this double consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity. One ever feels his twoness,—an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder. ~ W. E. B. Du Bois [1]

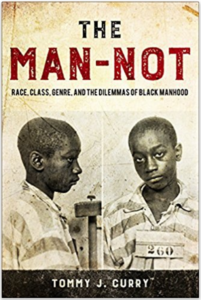

The lust—the libidinal desire—for the Black male’s body that serves as the motivation behind his condemnation and death is not altogether new. ~ Tommy J. Curry [2]

Black male bodies are bodies under siege. In the current historical moment, one polemical, ethical issue is the deadly interplay between the surveillance of black bodies and a burgeoning militarized police state. There are several sources of this extended surveillance and scrutiny of black male bodies in American race relations. Studies in higher education and the psychology of race have illustrated how black boys are mischaracterized as older in appearance and more aggressive in demeanor than their white counterparts.[3] There is also substantive research on the impact that implicit racial bias has on black men and boys in terms of health and well-being, imbalances in the criminal justice system, and overarching social stigma in everyday life.[4] This mode of surveillance and sanctioning, as we illustrate, also extends into the practices of sexual victimization of black boys and men, an understudied but prominent feature of the life experiences of black male bodies in past and contemporary American culture. Assaults against black male personhood and embodiment reveal the extent to which the American context has distinguished its racial hierarchy through the ostracizing of blackness-as-non-white. Such a social habitus featuring this racialized “twoness” reveals how black people and black bodies are problem people and problem bodies—imposing upon blacks America’s anxiety about “racial others.” To this end, we are concerned with a philosophical exploration of the experience and configuration of black bodies in Jordan Peele’s Get Out (2017) in light of the insights from W.E.B. Du Bois and in light of gender theories on the historical and contemporary constructions of black male sexuality and identity.

Du Bois’s theory of double consciousness provides one component of the theoretical lens we use to analyze Peele’s film. We investigate double consciousness, black male embodiment, and racial appropriation through an examination of the film’s symbolism relating to each as they influence the central character, Chris Washington. Du Bois outlined the former concept in The Souls of Black Folk (1903), while the themes of racial appropriation, exploitation, and surveillance of black male bodies were inaugurated in the slave trade and continue in contemporary cultural and economic practices.

Curry captures the dual quality of fear of and desire for black male flesh in the notion of phallicism. Phallicism, notes Curry, invites, and further legitimizes societal suspicion and scorn, both in academic theory and in social institutions toward black men. Curry writes:

Phallicism refers to the condition by which males of a subordinated racialized or ethnicized group are simultaneously imagined to be a sexual threat and predatory, and libidinally constituted as sexually desirous by the fantasies or fetishes of the dominant racial group.[8]

Drawing upon the historical constructions of black manhood from slavery to Jim Crow and into the present, Curry presents phallicism as a frame for anti-black male sentiment and the resulting architecture of race and place imposed upon black male bodies. In a societal context in which all “male genitalia is conceptualized as a weapon wielded against women,” views of black men as problematic only bodies with a genetic and primordially-based proclivity for sexual violence are proffered as evidentiary support for the sanctioning, controlling, and killing of black men.[9] Here, black men are always already the rapists, the brutes, the savages, etc.; however, in this schema, black men also represent sexual desire. Because there is long historical precedent of black men (and women) being “hypersexualized as objects of desire, possession, and want,” another feature of black male experience that is under-examined involves the reality of sexual victimization of black men and boys.[10] In the great zeal to imagine black men as the always-already-hyper-rapist, the sexual vulnerability of black men as subordinate men trapped in a racial and sexual hierarchy that denies their personhood and agency goes unchecked.

Phallicism, then, as an accepted perspectival apprehension of and desire for black male embodiment, legitimates the use of coercion and control of the black male body as an only-body within the larger racial ecology of white male and female supremacy. Chris’s ordeal in Get Out creatively highlights that phallicism as a frame for misandry is a function of the collective white American psyche on black male bodies. Given the scope of Curry’s insights on this point, we argue, first, that Chris’s experience of double consciousness in the film discloses the white lust for the black male body concealed by the thin banalities of white liberal progressivism. Second, we show that Get Out illustrates Curry’s conclusion that Black men are treated as only problematic bodies in need of administrative control. Last, we demonstrate that Get Out highlights a yawning gap between the reality of white women as proxy patriarchs, culpable in advancing white supremacy, and the mythical view of them as both pure and passive non-participants.

“Through the Eyes of Others”[11]

Chris’s early experiences vividly represent double consciousness. He sees himself as others see him, and his lack of true self-consciousness is a lack of true agency and autonomy. The premise features an uncomfortable Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner scenario depicting the black boyfriend’s meeting a white girlfriend’s family and friends. Rose Armitage, Chris’s girlfriend, has not disclosed Chris’s race to her parents, and she expresses the absurdity of ‘racing’ him, mockingly saying to Chris: “Mom and dad, my black boyfriend will be coming home this weekend.” Cursorily, Rose’s parents represent what Shannon Sullivan describes as “good white people.”[12] As Rose assures Chris before the visit, “they’re not racist.” They affect the veneer of stereotypical progressive white liberals who try to show superficial solidarity with Chris. Rose’s dad addresses Chris with a “Sup, my man?” and refers to Chris’s and Rose’s relationship as “this thang”—attempts to establish rapport through forced use of slang. The father considers this appropriation of what he imagines as a “code-switching,” urban speak as an authentic gesture of connection with his guest, to cement his credibility as a “good” white man, but his effort is sorely wanting. Even though the father presumably makes a “connection” based on some sense of shared understanding rooted in urbanized vernacular, he does not make an effort to know Chris beyond the cursory and surface level—rendering Chris still yet, a “problem.” The Armitages make no effort to know Chris beyond their restrictive epistemic glances—a fact that becomes more pronounced when we learn their actual intentions for Chris’s body.

Chris is a talented photographer who captures the white world through his filtered angle of vision, and this feature of his character further highlights the phenomenon of double consciousness. The camera extends his “second-sight,” enabling insight into “this American world.” Interestingly, one white person seeking Chris’s body wants to make use of this second sight. The blind art dealer, Jim, who is later to receive Chris’s body, openly clarifies his fascination with his sight. When Chris later asks about the rationale for the use of black bodies—“why black people?”—Hudson claims race is irrelevant: “What I want is deeper. I want your eye, man. I want those things you see through.” In this dynamic, the “second sight” of the black body is a source of fascination and admiration, but still collapses into the restrictive confines of desire for black male flesh.

The art dealer’s racial erasure as a factor in his decision to appropriate Chris’s body warrants additional criticism, particularly in light of implications that shed light on the intersections of race and disability. The art dealer sees in Chris’s body a pragmatic utility that presumably eschews any concern with race. Historically considered, the bodies of black men, as we note with Curry, are often constructed as only bodies—bodies subject to the control and coercion of white political, economic, and social hierarchies. The art dealer’s disability, his blindness, provides him with a non-raced rationale for obtaining Chris’s body. Here, it is Chris’s black body, and not the white male body, that is in the immediate, “ideal type.” Curry observes that interplay between embodiment and coercion involving the bodies of black men and white men was most always driven by the inconceivability on the part of whites to read black male bodies as anything other than problem bodies—bodies that require sanctioning and control.[13] With the art dealer, however, the presumption that those raced as black have “been constructed as the degenerate/inferior/nonhuman opposite to the rational prototype human/superior/(Western) (abled) human” is strikingly absent, but the control of black male flesh remains prominent.[14] While the abnormality and disability of the white male body reverses the rigid racialization of Chris’s raced body, his (color) blindness once again collapses into the remorseless subjugation of Chris’s body that has characterized the lion’s share of white racial responses, perceptions, and usage pertaining to black bodies. The terrain of race hierarchy and bodily desire that is often a feature of white fascination with black embodiment is slippery here.

“A Stranger in my own House”[15]

Rose’s parents, the Armitages, host a party where the guests observe Chris as if he is an exotic animal, while offering racially tone-deaf commentary. Rose’s brother, Jeremy, channels a racist trope linked to American slavery: he suggests Chris is bred to fight, again reducing him to the body. Frantz Fanon also spoke of this dynamic as the tendency of blacks to be “overdetermined from the outside,” that is, having agency or identity not of one’s choosing levied as an authentic representation of true selfhood.[16] Shortly after meeting Chris, Jeremy initiates a conversation about mixed martial arts during which Chris admits that he finds the sport “too brutal.” Jeremy laments this response, noting, “With your frame and genetic makeup, if you really pushed your body…you’d be a fucking beast.” Jeremy’s word choice illustrates how black bodies are constructed within the white racial imagination. Here, Black male bodies are animalistic bodies solely suited for hyper-aggression, a designation Eldridge Cleaver once described as the phenomenon of the “supermasculine menial.”[17] Jeremy emphasizes the point through a discussion of the martial art, Jiu Jitsu, which he imagines as reliant not upon physical prowess, Chris’s singular value, but as a “strategic game like chess” requiring greater intelligence. The implication is that Chris is the physically superior, but otherwise intellectually inferior being, valuable only for athletic labor.

The guests at the party treat Chris as what bell hooks calls the “native informant.”[18] They force Chris to be a spokesperson of the black race, which they presume is monolithic. The manner in which they press Chris to account for and represent blackness takes on an insidious tone with historical implications for the nature of racial perception and the white imagination. For example, they take sexual accessibility to Chris’s body for granted. An older female guest gropes Chris’s arms, demonstrating what Ken Stikkers describes as “ontological expansiveness,” a racial privilege enabling free access to space and place.[19] There is no space that she is not entitled to occupy, including Chris’s body. She also demonstrates degraded value for black bodies beyond that purposed for white interests. In referencing sex with Chris, the woman asks Rose: “Is it true? Is it … better?” She defines Chris by his body, vis-à-vis her sexualized gaze. This scene reflects one of the under-discussed mechanisms of black male vulnerability: the sexual victimization of black male bodies. Chris is reduced to the mythic black phallus, implicating and reinscribing a racial legacy that frames black men as both hypersexual and as perpetual rapists, but still subject to being preyed upon by white men and women. [20] [21]

Chris’s experience at the Armitage estate is both familiar and strange. The strangeness of the party sets the tone for the film’s transition from a mere clash of cultures to outright horror. He is accustomed to the micro aggressions and both the overt and thinly veiled racism under the guise of racial admiration. As Aisha Harris wrote, “That even surface-level ‘admiration’ for black culture on the part of white people can give way to insidious interactions that are, at best, a persistent annoyance black people must learn to laugh off, and, at worst, the kind of fetishization that only conceals deadlier preconceptions.”[22] Chris, like so many black Americans, has to distinguish between the comments of well-meaning, ignorant white people, the more nefarious racist intentions of others, and the ways the former can devolve into the latter.

“Plod Darkly in Resignation” to White Control[23]

The abnormality of the Armitage home includes their two black servants, Walter and Georgina, the groundskeeper and housekeeper. Both appear lifeless and unfeeling. They plod through the estate in quiet resignation. A third guest, a young black man, whose dress and speech patterns mimic those of an older, white man, plods darkly in like manner. His black body enfleshes a white persona, and his wife is a much older, white woman. Disconnected from black culture, he grasps, with an open hand, Chris’s attempt at a fist-bump. He is resigned to embodied slavery to his white wife, noting: “I find that I don’t have much desire to leave the house anymore.” The older woman then grasps his waist and says, “We’re such homebodies now.” Another source of Chris’s unique sight, his cell phone camera, inadvertently wakes this guest from assimilated slumber, known as “the sunken place”—a psychic prison housing a sliver of the formerly intact consciousness of the black host.

One of the messages underscoring the film’s plot centers on the ability of the sunken guests to regain race consciousness and black agency in the interstices of their oppression. Part of Chris’s struggle is to resist the compelling racial, psychological, and scientific forces that would render him unconscious and subject to white agency and control vis-à-vis the sunken place. In contemporary parlance, sunken blacks are not “woke”—they cannot recognize the nuances of their racial subjugation. Sunken consciousness is no consciousness at all; in this realm, white psychological, cultural, and intellectual reference points supplant “wokeness.” Part of the process of racial subordination and exploitation, as Cleaver observed, requires white control over the menial black body. Cleaver refers to whites, in this framing, as “omnipotent administrators.” In Get Out, the surgical mechanism to fuse white consciousness with black bodies manifests this administrative omnipotence.

Cleaver opined that omnipotent administrators subjugate menial bodies precisely through the dulling—the obsoleting of the “menial” consciousness and intellectual prowess. The administrators maintain control in society, quite literally, because of “mind over matter.” Cleaver’s explanation also addresses why during slavery whites enacted literacy codes making it unlawful for the enslaved to learn to read. When considered with the theme of consciousness and black male embodiment in Get Out, Rose’s mother, Missy, functions as omnipotent administrator by depriving Chris full consciousness through hypnosis—prompting his immersion into the sunken place. In so doing, she literally administers the process of subordinating Chris’s consciousness to white control. As the art dealer, Jim, says to Chris before the operation: “…you won’t be gone, not completely…your existence will be as a passenger…I’ll control the motor function.”

White Women as Proxy Patriarchs

While it is in fact the psychology and personality of the white male patriarchal “ideal” who will control Chris’s vessel, there is still the issue and importance of the white woman as the inaugurator of the entire process. White womanhood serves as proxy for white patriarchy. Both Rose’s and Missy’s characters embody this proxy as both are complicit in the administrations of Chris’s body.

When Cleaver delved into gender theory on whites and blacks, his conception of white women as the “ultrafeminine” was flawed. Per Cleaver, the white-woman-as-ultrafeminine is “delicate, weak, helpless.”[24] This view is problematic for its sexism and its ahistorical interpretation of the tensions and contradictions of white women as proxies, or rather, proxy patriarchs with tangential raced and gendered privileges. Framing white women as helpless counterparts to white males is sexist because it denies their agency and abilities to act; the damsel-in-distress trope relies on the same assumptions about women’s docility that ground much of Victorian gender ideality. Cleaver’s “ultrafeminine” conclusions are also problematic because they ignore and neglect the reality of white women’s promotion of white male supremacy and patriarchal power. Some of the most dutiful foot soldiers in the preservation and cultivation of white male identity formation as the patriarchal ideal and locale for racial power are white women.

Gail Bederman links, for example, early white feminist concerns about the march toward higher “civilization” to white male power and influence as the determinative feature of cultural progress. Using Charlotte Perkins Gilman as an example, Bederman opines that the turn to “civilized Anglo-Saxon womanhood” as a white feminist strategy, essentially secured the trappings of patriarchal power not by opposing white men as patriarchal oppressors, but through a radical acceptance of certain virtues that propelled the race forward against the rising tides of barbarism and savagery presumably embodied in other races, namely blacks. Gilman once suggested that in order to stem black male criminality, “non-progressing” black men who did not seem to embody “a certain grade of citizenship,” or cultural assimilation, should be compelled into military servitude until “graduation,” into the realm of authentic cultural nationalism. Gilman’s feminism was wedded to race loyalty over against gender and sex interests—thus indicating the curious fusion of white supremacism with many early expressions of white feminist ideology, theory, and praxis.[25] Other studies on white racialist movements and the politics of race within white communities provide much material on gendered expressions of racism and the centrality of white women. Recent tomes such as They Were Her Property: White Women as Slave Owners in the American South (2019) and Mothers of Massive Resistance: White Women and Politics of White Supremacy (2018) document how white women were often key players in the reifying of American racial and political economies, from slavery to the contemporary period.[26]

We must acknowledge reality of white women’s gender-based privilege as a construct that can be weaponized against black men—rendering black men devoid of any modality of patriarchal privilege solely based on manhood. In the context of the film, Chris is disempowered at the hands of white women, Rose and Missy. When Missy began the process of Chris’s hypnosis and immersion into the sunken place; she was not a dainty, dispassionate observer; she was a direct participant and recipient of his embodied benefits. Like a good proxy patriarch, she played her part. This long history of white women as historical actors in the degradation and displacement of black male bodies is a painful one, but contemporary scholarship must reckon with it. A failure to do so eschews the kind of complex interpretive strategies that enable us to more fully wrestle with the messy, non-linear connections that often interlock raced, sexed, and gendered constructions of power and how this impacts subordinate and subaltern male communities denied the trappings of privilege presumed to constitute the nature of manhood and masculinity.

Conclusion: “Warring Ideals”[28]

As a realistic depiction of the larger struggle to resist the push and pull on black identity, embodiment, and personhood, Get Out provides a useful lens to explore how black men navigate the complex webs of meaning attached to their bodies. The Armitages and their guests viewed Chris with both exoticism and amusement. If Du Bois’s analysis was accurate, perhaps it was with “amused contempt and pity.” They collectively engaged in gross reductionism—in those moments, “Chris” ceased to be. He became the amalgamation of their desires, gazes, and curiosities linked to his body. The “surface-level ‘admiration’” for Chris gave way to more “insidious interactions” and the kind of “fetishization” that conceals more insidious racial appropriation and anti-black racism.

Read Du Bois’s words as a description of Chris: “his twoness,—an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.”[29] In this passage, Du Bois illustrates that African-Americans are both Americans and Black, and these souls are at war. Chris sustains the American ideal as long as he can, but the Armitages see him only as a means to an end, a body for use. The first ideal is at work in his compassion. He trusts Rose and agrees to visit her family. He shows compassion for the deer Rose hit with the car and for Georgina, who he hits with Jeremy’s car during his escape. But the ideal for the conservation of his race and for his survival as a black man wars with the ideal that mutual compassion and recognition of black humanity can win the day in America. His friend Rod maintains this latter ideal, and Chris’s cell phone flash into Walter’s eyes raises Walter’s awareness of this ideal as well. He must fight to prevent black bodies from being “torn asunder” by the pernicious modes, both subtle and explicit, of white supremacy. The double consciousness operative in Chris’s character shows that underneath the thin pleasantries of white liberal progressivism one finds a sexual fetishizing of the black male body, but also indicates the outright disposability of black male bodies without consequences should those bodies escape white, administrative control.

Get Out uncovers some disturbing but realistic truths about the realities of black male embodiment in American culture. As Curry notes, Black men are largely reducible to only bodies—prey to white men’s and women’s control. Chris was able to evade the grievous fate tied to the loss of agency, consciousness, and will—he was able to safeguard and preserve himself. However, in our present reality there are far more mechanisms at play that continually displace black male humanity through the attachment of blackness to disposable flesh: racial profiling, a militaristic criminal justice system, and the myriad insidious biases that mar our public, political, educational, and economic infrastructures. Ultimately, the crux of the problem with framing black bodies as only bodies is the abject denial of non-white humanity. The film unpacks this feature of America’s racial legacy.

Notes

[1] The Oxford W.E.B. Du Bois Reader, Ed. Eric J. Sundquist, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996), 102.

[2] Tommy J. Curry, The Man-Not: Race, Class, Genre, and the Dilemma of Black Manhood (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2017), 35.

[3] See Phillip Attiba Goff et al., “The Essence of Innocence: Consequences of Dehumanizing Black Children,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 106.4 (2014): 526-545, 540.

[4] See Phillip Attiba Goff et.al, “Not Yet Human: Implicit Knowledge, Historical Dehumanization, and Contemporary Consequences,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 94.2 (2008): 292-306; Valerie Strauss, “Implicit racial bias causes black boys to be disciplined at school more than whites,” The Washington Post, April 5, 2018, (https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/answer-sheet/wp/2018/04/05/implicit-racial-bias-causes-black-boys-to-be-disciplined-at-school-more-than-whites-federal-report-finds/?utm_term=.d31f5807a352).

[5] George Yancy, Black Bodies, White Gazes: The Continuing Significance of Race in America, Second Edition, (Rowman and Littlefield, 2017) xiv.

[6] The distortion of African American selfhood and personality, particularly through popular stereotypes, is obviously not limited to black men. Womanist ethicist Emilie Townes takes up this cultural phenomenon as it impacts black women in American race relations in Womanist Ethics and the Cultural Production of Evil (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006).

[7] Curry, The Man-Not, 6.

[8] Curry, “Killing Boogeymen: Phallicism and the Misandric Mischaracterizations of Black Males in Theory,” in Res Philosophica, Vol. 95, No. 2, (April 2018), 265.

[9] Curry, Killing Boogeymen, 264.

[10] Ibid., 265.

[11] The Oxford W.E.B. Du Bois Reader, 102.

[12] Shannon Sullivan, Good White People: The Problem with Middle-Class White Anti-Racism, (SUNY Press, 2014).

[13] Tommy J. Curry, “This Nigger’s Broken: Hyper-Masculinity, the Buck, and the Role of Physical Disability in White Anxiety Toward the Black Male Body,” in The Journal of Social Philosophy, 48: 321-343. doi: 10.1111/josp.12193

[14] Ibid., 322.

[15] The Oxford W.E.B. Du Bois Reader, p. 102.

[16] Frantz Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks (New York: Grove Press, 1967), 116.

[17] Eldridge Cleaver, Soul on Ice (New York, Delta Books, 1999), 209.

[18] bell hooks, Teaching to Transgress, (London: Routledge, 1994), p. 43.

[19] Kenneth Stikkers, “…But I’m Not Racist”: Toward a Pragmatic Conception of “Racism,” The Pluralist, Vol. 9, No. 3 (Fall 2014), pp. 1-17.

[20] Curry takes up the sexual victimization and exploitation of black men in chapter 2 of The Man-Not, but see Thomas A. Foster, “The Sexual Abuse of Black Men under American Slavery,” Journal of the History of Sexuality, Volume 20, Number 3 (September 2011), pp. 445-464.

[21] Curry, Man-Not, 91-92.

[22] Aisha Harris, Get Out (Review), Slate, Feb. 23, 2017.

[23] The Oxford W.E.B. Du Bois Reader, p. 102.

[24] Cleaver, Soul on Ice, 217.

[25] Gail Bederman, Manliness and Civilization: A Cultural History of Gender and Race in the United States, 1880-1917 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), Ch.4.

[26] Stephanie E. Jones-Rogers, They Were Her Property (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019); Elizabeth G. McRae, Mothers of Massive Resistance (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018).

[27] Tommy Curry, “He’s a Rapist, Even When He’s Not: Richard Wright’s Account of Black Male Vulnerability in the Raping of Willie McGee,” in The Political Companion to Richard Wright, ed. Jane Gordon (Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 2018).

[28] The Oxford W.E.B. Du Bois Reader, p. 102.

[29] The Oxford W.E.B. Du Bois Reader, Ed. Eric J. Sundquist, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996), p. 102.

References

Bederman, Gail. Manliness and Civilization: A Cultural History of Gender and Race in the United States, 1880-1917, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996.

Cleaver, Eldridge. Soul on Ice. New York: Delta Books, 1999.

Curry, Tommy J. The Man-Not: Race, Class, Genre, and the Dilemmas of Black Manhood. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2017.

–––. “He’s a Rapist, Even When He’s Not: Richard Wright’s Account of Black Male Vulnerability in the Raping of Willie McGee,” in The Political Companion to Richard Wright, ed. Jane Gordon. Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 2018.

–––. “Killing Boogeymen: Phallicism and the Misandric Mischaracterizations of Black Males in Theory.” Res Philosophica, Vol. 95, No. 2 (April 2018): 235-272.

The Oxford W.E.B. Du Bois Reader. Ed. Eric J. Sundquist. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996.

Foster, Thomas A. “The Sexual Abuse of Black Men under American Slavery.” Journal of the History of Sexuality, Volume 20. Number 3 (September 2011): 445-464.

Goff, Phillip Attiba, et al. “The Essence of Innocence: Consequences of Dehumanizing Black Children.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 106.4 (2014): 526-545.

–––. “Not Yet Human: Implicit Knowledge, Historical Dehumanization, and Contemporary Consequences.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 94.2 (2008): 292-306.

Harris, Aisha. Get Out (Review). Slate, Feb. 23, 2017.

hooks, bell. Teaching to Transgress. London: Routledge, 1994.

Jones-Rogers, Stephanie E. They Were Her Property. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019.

McRae, Elizabeth G. Mothers of Massive Resistance. New York: Oxford University Press, 2018.

Stikkers, Kenneth. “. . . But I’m Not Racist”: Toward a Pragmatic Conception of “Racism,” The Pluralist 9, No. 3 (Fall 2014): 1-17.

Strauss, Valerie. “Implicit racial bias causes black boys to be disciplined at school more than whites,” The Washington Post, April 5, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/answer-sheet/wp/2018/04/05/implicit-racial-bias-causes-black-boys-to-be-disciplined-at-school-more-than-whites-federal-report-finds/?utm_term=.d31f5807a352.

Sullivan, Shannon. Good White People: The Problem with Middle-Class White Anti-Racism. SUNY Press, 2014.

Townes, Emilie. Womanist Ethics and the Cultural Production of Evil. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006.

Yancy, George. Black Bodies, White Gazes: The Continuing Significance of Race in America. Second Edition. Rowman and Littlefield, 2017.