| By Shane Courtland |

After reading a thoughtful response from Dr. Hay regarding my previous blog post, I thought it would be helpful to discuss my philosophical pedagogy. Even if you have never taken a philosophy class before, the core elements of my teaching method are still applicable outside of the classroom. Moreover, describing how I teach philosophy should better show what I mean when I say that “Philosophy is a method” and “I worship that method.”

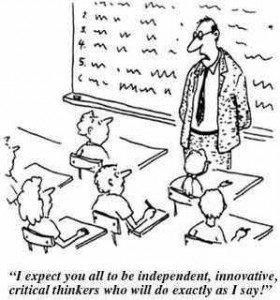

When we discuss various topics, I insist that the class be bound by three rules. Their observance helps facilitate learning of the philosophical method. They are as follow:

- In my class, you not entitled to your own beliefs. Everything that you claim to be true in class, you must be able to justify via argumentation. If you get “called-out” to justify your view and you cannot … you must, at least for the time you are in class, give up the claim that others should agree with your view. Obeying this rule means that no one can stop discussion by merely saying, “Well, I have a right to my own opinion.”

- If you assert a view, the burden of proof is on you. If you get “called-out” to meet the burden, and you cannot … you must, at least for the time you are in class, give up that view. Obeying this rule means that no one can rebut criticism by merely replying, “Well, show me that I am wrong.”

- You must be civil. You cannot use hate speech (narrowly defined, as by law); there can be no threats of violence; there is no interrupting; etc.

With these rules respected, I will entertain any questions or claims pertinent to our class discussion. And, when I mean any, I mean that I will only stop the discussion for pragmatic considerations (e.g., the discussion is too much of a tangent, we are running out of class time, etc.).